Source: Link

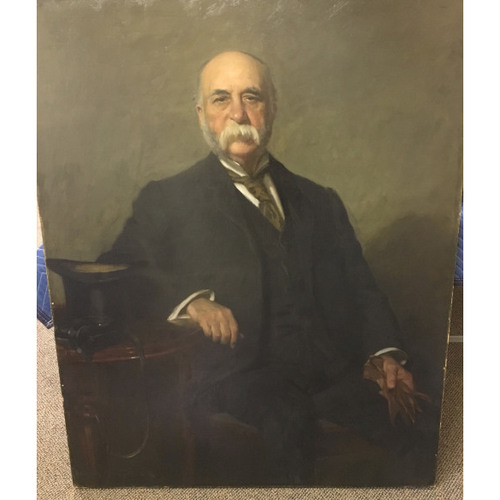

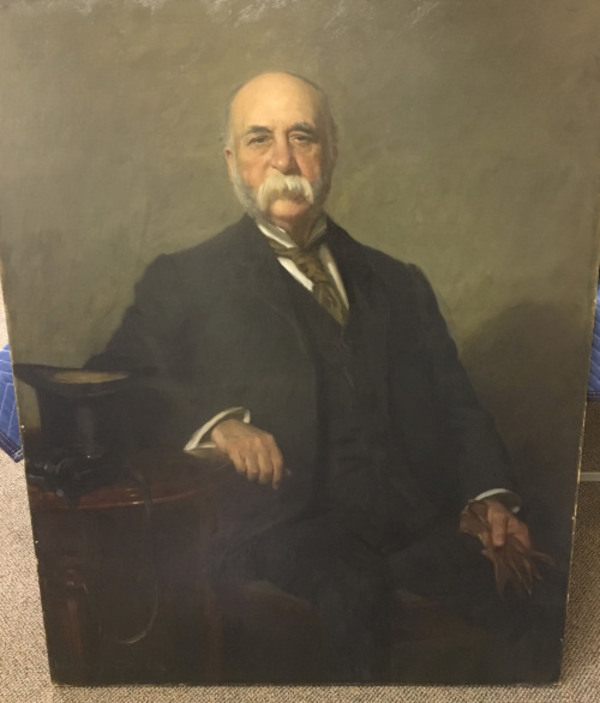

SMITH, ANDREW, veterinary surgeon, educator, and author; b. 12 July 1834 in Dalrymple, Scotland, only child of James Smith and Agnes McNider; m. 15 Sept. 1863 Mary Anne Hornsby in Toronto, and they had four sons and three daughters (three sons and one daughter died in childhood); d. there 15 Aug. 1910.

After attending parish school, Andrew Smith worked on the family’s 160-acre farm, raised prize stock, and served as secretary of the local agricultural society. At age 25 he entered the Edinburgh Veterinary College. He graduated in 1861 with high honours and received the diploma of veterinary surgeon from the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland. He then applied for a position as a veterinary officer in the British army, but an opportunity awaited him in Upper Canada instead. Concern over the lack of people qualified to guard the province’s increasing livestock population against disease had prompted Adam Fergusson*, of the Board of Agriculture of Upper Canada, and George Buckland*, professor of agriculture at the University of Toronto, to seek a suitable person to head a school to train veterinarians. On the recommendation of Professor William Dick at the Edinburgh school, Smith was appointed veterinary surgeon to the board. He arrived in Toronto on 23 Sept. 1861, a short, solidly built young man, with dark hair and a beard, a serious, almost sombre countenance, a dignified manner, and, as it would turn out, a store of persistence and sound business judgement.

Smith began practising on 1 Jan. 1862 from a “horse infirmary and veterinary establishment” in leased buildings. On 12 February he gave the first in a series of lectures on veterinary subjects in conjunction with a winter course in agriculture provided free to the public by the board. The lectures, repeated the following winter, were the genesis of the Upper Canada (sometimes called the Toronto) Veterinary School, the first of its kind in Canada. In 1864 Smith began a “regular” course which, following the British model, consisted of two six-month sessions over two years and culminated in examinations. To the oral instruction, he added anatomical demonstrations in an unheated shed behind the infirmary; these were given in November, no doubt because it was cool enough to preserve subjects for dissection but not too cold for the students. Graduates were awarded a diploma by the board and, after 1868, by its successor, the Agricultural and Arts Association of Ontario. Three men in 1866 were the first graduates; they were entitled to place vs after their names to distinguish them from farriers and empirics who had no formal training but who often styled themselves “veterinarians.”

For 46 years the college would reflect the views and management of Smith. As proprietor and administrator, he provided the facilities and paid the faculty, drawn from the profession and from the university, including Buckland and James Bovell*; as principal and professor, he determined the curriculum, and selected, taught, and disciplined the students. The emphasis at first was on equine diseases because of the importance of horses for farming operations and for transportation. In 1867 he published The Canadian horse and his diseases (Toronto) with Duncan McNab McEachran*, a fellow graduate of Edinburgh whom he had persuaded to come to Canada to teach at the college. Oriented as Smith’s course was towards the practical veterinary arts and with virtually no educational prerequisite, it proved popular. In 1869–70 he erected the first veterinary teaching building in Canada, the Ontario Veterinary College, which he enlarged in 1876. With the number of students approaching 400, Smith added a new building in 1889. A “dissecting room,” built in 1890, was the last of his expansions.

Determined that his graduates, unlike the empirics, be recognized as qualified professional practitioners, he promoted the formation on 24 Sept. 1874 of the Ontario Veterinary Medical Association for “the mutual improvement of its members . . . and the advancement of the position and interests of the Veterinary profession in the Province.” Smith was president until 1879 when it was incorporated as the Ontario Veterinary Association, and he remained its moving force. The annual meetings were held in the college, and he urged members to participate in the accompanying “scientific” programs, initially just descriptions of cases but eventually including prepared addresses. The meeting of 1903 heard papers by both Andrew and his son, David King Smith, who taught pathology at the college. From 1884 a committee, with Smith Sr as a member, strove unsuccessfully to obtain legislation making it unlawful for an unqualified person to practise veterinary medicine in the province, and thereby giving the public protection as well as the profession.

Smith upgraded his own qualifications. He became a member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons in 1880, and was elected an honorary associate the following year; in 1888 he became a fellow by examination. In 1909 he received an honorary doctorate in veterinary science from the University of Toronto. He also served as veterinary surgeon of the Toronto Field Battery, dominion inspector of stock for Ontario, judge at horse shows in the United States and overseas, consultant to the Ontario commissioner of agriculture in 1884 on measures to control contagious equine diseases, and member in 1892 of an Ontario commission on the dehorning of cattle. In 1883 some of his lectures were published under the title Veterinary notes.

Smith’s interest in horses carried over into private life. As a youth he won races as a steeplechase rider. He owned racehorses and in 1883 he helped start the Toronto Hunt Club, in which he was master of the hunt for ten years. A founder of the Ontario Jockey Club, a charter-member of the Canadian National Horse Show Association, and a member of the horse-breeders’ National Club, he also found time to be honorary governor of the Toronto General Hospital, director of the Consumers’ Gas Company, and one of the founders, president, and director of the Industrial Exhibition in Toronto. True to his Scottish heritage, he was a member of St Andrew’s Church (Presbyterian) and the St Andrew’s and Caledonian societies, and a master of the St Andrew’s masonic lodge.

Controversy over the length and content of the curriculum and the easy admission and graduation requirements dogged Smith’s college almost from its inception. McEachran had resigned in 1866 to start a rival college in Montreal with a three-year program that allowed for fuller instruction in the sciences and with entrance and graduation standards that were high for the day. Smith, anxious that the popularity of his college not be diminished, resisted pressure for change. He strengthened his control by incorporating the college in 1897, enabling it to issue its own diplomas. The college also became affiliated with the University of Toronto in that year. Smith, however, did not provide a course leading to a degree from the university, and by the turn of the century it was plain that veterinary education in Ontario had fallen behind the times. Rising educational standards in the province, the heightened role of stock-raising and dairying, advances in scientific knowledge, and the trend to longer veterinary courses elsewhere (four years in Britain and as many as six or seven years in Europe), all emphasized the need for improvement. Led by John Gunion Rutherford*, the profession began to call for the Ontario government to take over the college. The Farmer’s Advocate and Home Magazine (London, Ont.) deplored in 1901 that graduates required another year of study in order to qualify for employment as dominion meat inspectors or for practice in Manitoba because the college was “run on the plan of dear old Doctor Dick (Edin), doubtless very useful fifteen or twenty years ago, but . . . utterly unfit for to-day.” In 1906 Smith finally announced that the course would be extended to three years. He also entered into negotiations by which in 1908 he leased the buildings to the minister of agriculture and the OVC became a provincial institution. He was made professor emeritus and retained an office at the college, where Edward Alexander Andrew Grange was now principal; he liked to visit daily until he fell ill in the early summer of 1910 with blood poisoning. He died two months later.

As founder of the first veterinary college in Canada, Smith has been criticized for his conservatism and for the shortcomings of the OVC. Nevertheless, he seems to have been justified in considering that his form of veterinary education was the practicable one to introduce into the young country. While many contemporary proprietary colleges, including McEachran’s, had short lives, his thrived. By 1908 the OVC had produced 3,365 graduates. In 1965 it became part of the University of Guelph. Moreover, the OVA, which was his creation, ultimately placed veterinary medicine among the self-governing professions in Ontario.

A series of Andrew Smith’s lectures were published as Veterinary notes, printed from a corrected copy of shorthand notes, taken by R. W. Stewart, of an entire course of lectures delivered by Prof. A. Smith, v.s., on the causes, symptoms and treatment of the diseases of domestic animals, given before the class of veterinary students, at the Ontario Veterinary College, of Toronto, Canada, during the session of 1881–82 ([Columbus, Ohio, 1883]); subsequent editions appeared at Toronto in 1885, 1889, and 1891 under the title Veterinary notes delivered by Prof. A. Smith . . . at the Ontario Veterinary College, of Toronto, Canada. The 1885 edition has been reprinted (n.p., [1981?]); copies of both the original and the reprint are in the library of the Univ. of Guelph, Ont.

CTA, RG 5, F, St Andrew’s Ward, 1862–63, 1870, 1877, 1890. Ontario Veterinary College Museum, Univ. of Guelph, Andrew Smith coll. Univ. of Guelph Library, Arch. and Special Coll., RE1 OVC A0088 (Ontario Veterinary College, Faculty, Ontario Veterinary Assoc. minutes), 1874–1910. Farmer’s Advocate and Home Magazine, esp. 1 March 1897, 2 Jan. 1899, 15 July 1901. Globe, esp. 17 Oct. 1861, 16 Aug. 1910. C. A. V. Barker, “The ‘dissecting room’ of the Ontario Veterinary College of 1890–1914,” “John G. Rutherford and the controversial standards of education at the Ontario Veterinary College from 1864 to 1920,” “The Ontario Veterinary College: Temperance Street era,” “Robert Robinson, 1836–1901: one of OVC’s first three,” and “The Toronto Veterinary School (Ontario Veterinary College) buildings, 40–42 Temperance Street, 1862–1875,” in Canadian Veterinary Journal (Ottawa), 28 (1987): 65–67; 18 (1977): 327–40; 16 (1975): 319–28; 31 (1990): 461–63; and 29 (1988): 754–57, respectively; “Notes on the history of the Ontario Veterinary College” (typescript, Guelph, 1987; rev. 1990; copy in Ontario Veterinary College Museum). M. L. Barnes, “Andrew Smith, founder, Ontario Veterinary College,” Ontario Veterinary College, Univ. of Guelph, OVC Alumni Centennial Bull., 1967: [5–6]. Canada Farmer (Toronto), esp. 3 (1866), 2 April, 1 May; 5 (1868), 16 April; new ser., 1 (1869), 15 Dec.; 2 (1870), 15 March. Canadian Agriculturist (Toronto), esp. 14 (1862), issues of 1 Jan., 16 Nov., 1 Dec. A. M. Evans and C. A. V. Barker, Century one: a history of the Ontario Veterinary Association, 1874–1974 (Guelph, 1976). F. E. Gattinger, A century of challenge: a history of the Ontario Veterinary College ([Toronto], 1962). Ontario Veterinary College, Annual announcements (Toronto), 1875/76–1907/8. U.C., Board of Agriculture and Agricultural Assoc., Journal and Trans. (Toronto), esp. 1 (1846–55): 39; Trans. (Toronto), 4 (1859–60): 102; 5 (1860–63): 212; 6 (1864–68): 8, 566.

Cite This Article

A. M. Evans, “SMITH, ANDREW,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smith_andrew_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smith_andrew_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | A. M. Evans |

| Title of Article: | SMITH, ANDREW |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 22, 2025 |