Source: Link

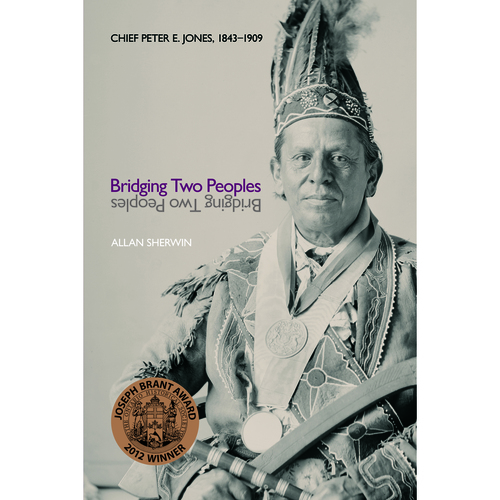

JONES, PETER EDMUND (Kahkewaquonaby), physician, Mississauga Ojibwa chief, Indian agent, and newspaperman; b. 30 Oct. 1843 in London, Upper Canada, son of Peter Jones* and Elizabeth Field*; m. 27 Feb. 1873 Charlotte Elvin, widow of William Dixon, in Brantford, Ont.; they had no children; d. 29 June 1909 in Hagersville, Ont.

A cultural gulf separated Peter Edmund Jones from many of his fellow Mississauga of the Credit. He had spent his early boyhood near London at the Muncey Mission, where his father, also named Kahkewaquonaby, was a Methodist minister. He then lived at Brantford in a largely non-Indian world. At the Joneses’ English-style country home a governess helped with his education until he entered Brantford Grammar School. Subsequently he attended medical school at the University of Toronto and Queen’s College at Kingston. He received his md in 1866, one year before Oronhyatekha, and was thus probably the first Canadian status Indian to obtain the degree.

Jones idealized the memory of his father, who had died when he was 12, and followed his example by working in an Indian community. He settled at Hagersville and practised among the Mississauga of New Credit. From 1874 to 1877, and again from 1880 to 1886, he served as head chief. He wanted to gain for Canada’s Indians, without the surrender of their legal Indian status, the civil rights enjoyed by other British subjects, including the franchise. Through his excellent connections with the Conservative party, he also urged the federal government to grant the bands more control over their own administration. After he failed to obtain sufficient power for them, he solicited and received an appointment as the first Indian agent to his band, a post he held from 1887 to 1896, when the Conservatives lost the federal election.

Although Jones was only one-quarter Indian, he identified with that aspect of his heritage. One year after his marriage to the English-born Charlotte Dixon he told a council that if they had children, he wished to train them “to be Indian children.” Yet not all his own band, not even all his relatives, thought this aim possible. David Sawyer [Kezhegowinninne*], an elder, believed Indian law to be “that a person of less than one-fourth Indian blood ceases to be an Indian.” None the less, Jones’s leadership had the support of the majority of band members, and an attempt by his cousin George Henry to dislodge him as official doctor met with failure. Jones continued his medical practice during and after his terms as chief and Indian agent.

A man of many interests, Jones edited and published his own newspaper, the Indian, for one year in the mid 1880s. He collected native artefacts, had a fine library on North America’s native people, and saved many of his father’s valuable papers and books. He played chess avidly, and, in a striking departure from native custom, practised taxidermy. A visitor to his home on the reserve recalled his “fascinating array of wild creatures, so cleverly mounted.”

Jones was short, with a dark complexion, a broad face, and high cheekbones. All his life he suffered from lameness in one leg; as a boy he had had to use crutches, and as an older man he walked with a cane. In his early sixties he developed a cancer below his tongue, and the disease eventually killed him. He had been an Anglican for many years, and he died a Christian, but one large in his views.

To the more traditionally minded individuals in his band, men such as David Sawyer and George Henry, Jones was a great puzzle. Equally he must have been an enigma to Indian department officials who encouraged university-trained natives to relinquish their Indian status. From the vantage point of the present, however, he seems more comprehensible. Although like many people of native ancestry today he had been raised largely in a non-Indian society, he identified himself as an Indian and took pride in his heritage.

[Information concerning Peter Edmund Jones was provided by a great-nephew, Macdonald Holmes of Edmonton, in his interview with the author on 3 Oct. 1976. Mr Holmes, who was 75 at the time of our conversation, had known Dr Jones during his early boyhood in Hagersville, Ont. d.b.s.]

Jones published 24 issues of the Indian (Hagersville) from 30 Dec. 1885 to 29 Dec. 1886. He is also the author of “Red man v. white man,” a letter printed in the Toronto Mail of 14 Dec. 1875: 2; “The Indians of Haldimand,” an entry in the Illustrated historical atlas of the county of Haldimand, Ont. (Toronto, 1879), 9–10; and a letter to Sir John A. Macdonald* dated 30 May 1885 and signed “Chief Kahkewaquonaby, m.d.,” in Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1885: 2371. His reports on the Mississauga of New Credit for the Dept. of Indian Affairs appear in its Annual report (Ottawa), 1887–96.

Manuscript letters by Jones are available in NA, MG 26, A: 62348–50, 209783, 209818–20, 211992–95; MG 29, D22, Jones to Miss Merritt, 4 March 1899; Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Arch. (Washington), Jones to H. F. Gardiner, 25 May 1898; and Wis., State Hist. Soc. (Madison), Draper mss, Joseph Brant papers, 13F13, Jones to W. L. Stone, 31 Oct. 1882; Jones to Lyman Draper, 12 Nov. 1882.

NA, RG 10, 2207, file 41812; 2238, file 45742. D. B. Smith, Sacred Feathers: the Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians (Toronto and London, 1987).

Cite This Article

Donald B. Smith, “JONES, PETER EDMUND (Kahkewaquonaby),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_peter_edmund_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_peter_edmund_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | JONES, PETER EDMUND (Kahkewaquonaby) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |