Source: Link

DAVIDSON, JOHN IRVINE, businessman, office holder, and militia officer; b. 17 Nov. 1854 in Wartle, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, sixth son of Samuel Davidson, a physician, and Margaret Watson; m. 20 Nov. 1878 Mary Hay in Toronto, and they had two daughters and a son; d. there 28 April 1910.

John Irvine Davidson received his formal education in the Wartle parish school and in Aberdeen. His practical instruction began in London, where he acquired knowledge of the wine and tea business. Possessing an independent spirit but little wealth, he immigrated to Canada around 1872. He soon found work as a salesman with the wholesale grocery firm of George Michie and Company in Toronto. Davidson subsequently spent time in Montreal with another wholesaler, James Jack and Company, but his connection with Toronto was solidified in 1878 when he married a daughter of local furniture manufacturer and mp Robert Hay*.

Davidson settled in Toronto by 1880, at which time he was still a commercial traveller. He soon became manager of John Charles Fitch’s wholesale grocery business on Yonge Street, and by 1881 he was a partner. When Fitch retired less than seven years later, Davidson acquired his interest. He then formed a partnership with his brother-in-law, John Dunlop Hay, and over the next few years Davidson and Hay established a reputation as one of the country’s largest wholesale grocers. Davidson’s ventures into wholesale lumber and grocery brokerage were not so successful.

As Davidson and Hay survived changing economic conditions – it would be incorporated in 1896 – its president enjoyed a growing prominence in business affairs. He was among a group of merchants who, beginning in the 1880s and in the hope of receiving improved service and competitive freight rates, supported the Canadian Pacific Railway during its battle with the Grand Trunk to gain a foothold along Toronto’s Esplanade. Similar concerns probably lay behind his decision in 1895 to promote the Toronto and Montreal Steamboat Company. His stature in the grocery business was recognized in 1904 when he was elected vice-president for Ontario in the Dominion Wholesale Grocers’ Guild. In the field of finance he had become a director of the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1886 and its vice-president in 1890. He also served as a director of the Home Bank of Canada and a vice-president of the Union Trust Company. The latter had been set up in 1900 by the Independent Order of Foresters, a fraternal organization that was heavily involved in life insurance [see Oronhyatekha]. The relationship between the order and the trust company, including their controversial investment practices, became a focus of attention for the federal royal commission on life insurance in 1906, and Davidson appeared as a witness.

Davidson’s profile was enhanced by his involvement with the Toronto Board of Trade, which he joined in 1883. His two-year term as president (1890–91) was marked by the completion of the board’s impressive new building, a project that had degenerated into scandal, but in his annual reports Davidson seemed preoccupied by issues farther afield. In imperial trade he stressed the need for a treaty with Britain that would give Canadian goods preference over goods from the United States, a position he would advance in 1892 in London at the second Congress of Chambers of Commerce of the Empire. (Five years later the board would exult at the reduction of the tariff on imported goods of British origin.) In Ontario, where a royal commission had highlighted the wealth of mineral resources in the province’s north, he heralded Toronto’s role, as a financial-service and industrial centre, in their development. He viewed the situation firsthand when the Canadian Copper Company invited representatives of the board to visit its Sudbury mines in December 1890 [see Samuel J. Ritchie]. Shortly after his return he reported to the board, “I find it difficult to keep within bounds of moderation when I contemplate the possibilities of those northland nickel riches of ours.” His interest seems to have shifted to more precious metals later in the 1890s, when he assumed the presidency of Cobalt Silver-Queen Limited and the St Paul Gold Mining Company.

Much closer to home, Davidson’s report to the board for 1891 advocated the construction of smelters, factories, and warehouses on lands to be reclaimed from the polluted marshes of Ashbridges Bay, at the east end of Toronto Harbour. The question was not whether the work should be done, but who should do it: a private syndicate or the municipal government. Citing Massachusetts’s successful development of Boston’s Back Bay, Davidson proposed a rationale that would dominate the board’s campaign to revamp the local port authority, and result in the formation of the Toronto Harbour Commissioners in 1911 and the start of reclamation in 1914.

Davidson recognized not only the city’s responsibility to provide the infrastructure necessary to support a growing population and economy, but also the need to place its administration in the hands of technically qualified people. This group did not include members of city council, particularly “the ward politicians, the ringsters, and the nominees of societies who exercise the rule over us.” Davidson was chafed by the fact that it cost more to administer Toronto in 1890 than it did to run the province. His efforts to advance the cause of municipal reform by supporting the mayoralty campaign of Edmund Boyd Osler* in 1891–92 met with considerable criticism, notably from the Toronto News. “An educated public opinion we have not got,” Davidson replied, “neither can we look for it until the ratepayers come to regard the city’s business as their business. And, so I emphasize the importance of the consideration of questions of city government upon the Board of Trade.” Such remarks illustrate the enduring perception of the board’s membership that the interests of Toronto should be closely allied with those of its merchant community.

Support for this point of view was reflected in several attempts to have Davidson stand for the mayor’s office, as well as for seats in the provincial and federal legislatures on behalf of the Liberal-Conservatives. Business considerations and a dislike of notoriety underlay his refusal, but on occasion he did foray into public life. In the municipal election campaign in December 1894 and January 1895, he was chairman of the Citizens’ Civic Reform Committee. In addition, he, Joseph Wesley Flavelle*, and John Alexander Murray were appointed liquor-licence commissioners for Toronto on 3 April 1905 by the provincial government of James Pliny Whitney*. Responsible for supervising the granting and renewal of liquor licences and the enforcement of liquor laws, they produced grim reports of intoxication and fraud, and announced their intention of rigidly enforcing the laws. Any progress was dashed when they resigned on 28 Nov. 1905 after their staff of inspectors, all Liberal appointees, had been replaced by Conservative supporters. The local prominence of Davidson and the others helped to stoke the ensuing debate over patronage, one of the worst moments of the Whitney administration’s first year.

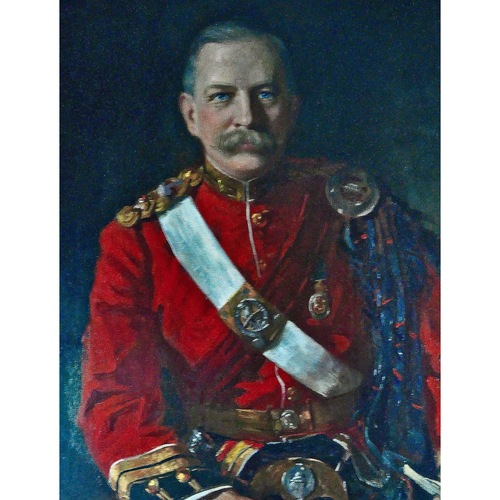

For all that Davidson avoided life in the public eye, he felt comfortable in a military career that was long and distinguished. His training had begun in Britain with two years in the 7th Aberdeenshire Rifle Corps, followed by time in the 15th Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps (London Scottish) and in the “Uxbridge Yeomanry” (probably the Middlesex Yeomanry Cavalry). Upon arriving in Canada, he joined the 10th Battalion of Infantry (Royal Regiment of Toronto Volunteers); he served with it for six years, rising to the rank of captain. His career took a marked turn in the summer of 1891, when representatives of local Scottish societies met to make plans for a Highland battalion similar to Montreal’s 5th Battalion of Infantry (Royal Scots of Canada). As the organizing committee continued to pressure the federal government to approve the unit, Davidson’s name was put forward as commander by Alexander Fraser*, secretary of the Gaelic Society of Toronto. Davidson accepted the tentative offer in July, and was added to the committee to consider a name and uniforms for the unsanctioned unit. His suggestion of the “Queen’s Highlanders” was rejected by the Department of Militia and Defence, which instead offered the unit a vacant number in the infantry list. The 48th Battalion of Infantry (Highlanders) was gazetted on 16 October; Davidson’s provisional appointment of 20 November as lieutenant-colonel commanding was confirmed on 25 March 1892. At Fraser’s suggestion the unit chose kilts of Davidson tartan in his honour.

The regiment prospered under Davidson’s care. On 16 March 1898, having reached his service limit, he relinquished command and accepted the position of honorary lieutenant-colonel. He assumed command of the Toronto-based 16th Infantry Brigade in 1905. The promotion in 1907 of Sir Henry Mill Pellatt* to the rank of colonel commandant of the 2nd Regiment (Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada), over 140 senior officers on the active list, resulted in much debate and was reputedly a factor in Davidson’s resignation from the infantry that year.

Davidson’s endeavours had brought him considerable respect and influence by the beginning of the 20th century. His opinions were sought by the press on matters ranging from increases in salaries for mps and judges in 1905 to imperial naval defence in 1909. He served as president of the St Andrew’s Society and the Sons of Scotland, and was chairman of the board of managers at St Andrew’s Church (Presbyterian) for several years. He also served as treasurer of the Toronto Humane Society and vice-president of the St John Ambulance Association. But just as he found himself in increasing demand outside his professional circles, he was struck by cancer and died in April 1910, within a year of diagnosis. The funeral service at St Andrew’s was attended by Lieutenant Governor John Morison Gibson*, city officials, and officers from all the units in the Toronto garrison, and crowds gathered in the streets to witness the military procession to Mount Pleasant Cemetery. As the guard of Highlanders passed by, onlookers saw a long line of Davidson kilts, which today perpetuate the memory of John Irvine Davidson.

St Andrew’s Church (Presbyterian) (Toronto), Reg. of marriages, no.745 (mfm. at AO). Evening Telegram (Toronto), 30 April 1910. News (Toronto), 1891–92. Toronto Daily Star, 29 April 1910. Armstrong and Nelles, Revenge of the Methodist bicycle company. Michael Bliss, A Canadian millionaire: the life and business times of Sir Joseph Flavelle, bart., 1858–1939 (Toronto, 1978). Canada Gazette, July–December 1891: 978; January–June 1892: 2001. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1901–10. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Directory, Toronto, 1875–1911. Alexander Fraser, The 48th Highlanders of Toronto, Canadian militia; the origin and history of this regiment and a short account of the Highland regiments from time to time stationed in Canada (Toronto, 1900). Hist. of Toronto. Frances Nordlinger Mellen, “The development of the Toronto waterfront during the railway expansion era, 1850–1912”

Cite This Article

Michael B. Moir, “DAVIDSON, JOHN IRVINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davidson_john_irvine_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davidson_john_irvine_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael B. Moir |

| Title of Article: | DAVIDSON, JOHN IRVINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |