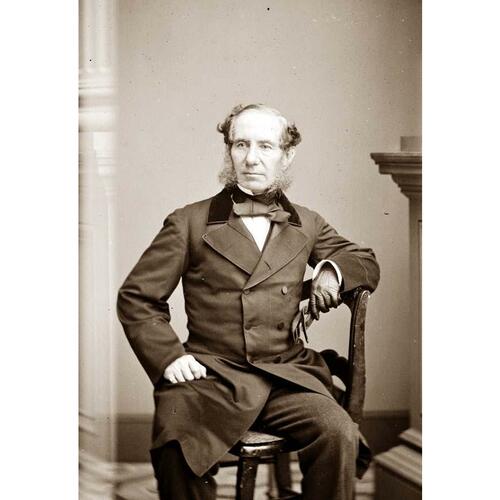

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ARCHIBALD, Sir EDWARD MORTIMER, lawyer and office-holder; b. 10 May 1810 at Truro, N.S., fifth son among 15 children of Samuel George William Archibald* and Elizabeth Dickson; m. 10 Sept. 1834 Katherine Elizabeth Richardson, and they had two sons and six daughters; d. 8 Feb. 1884 in London, England.

From the time that the Archibald family settled at Truro in 1762, it was prominent in the public life of Nova Scotia, particularly in the fields of law and politics. Edward Mortimer Archibald was to follow in this tradition. He attended private elementary schools at Truro and was enrolled in the newly established Halifax Grammar School when his father moved to Halifax to assume the offices of attorney general and surrogate of the Vice-Admiralty Court of the province. Edward was later a pupil at Thomas McCulloch*’s Pictou Academy before entering his father’s office to study law. In 1831 he was called to the bar of Nova Scotia. On 10 October of that year he was appointed chief clerk and registrar of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland on the resignation of his brother Charles Dickson*. Edward did not arrive in St John’s to assume office, however, until 8 Nov. 1832. He immediately began to practise as a barrister and attorney and so quickly demonstrated his competence that when, toward the end of 1833, there was a temporary vacancy in the Supreme Court, Governor Thomas John Cochrane* appointed Archibald acting assistant judge. He held that position through the ensuing term and during the midsummer term of 1834, discharging his duties efficiently.

Archibald had arrived in Newfoundland on the eve of the inauguration of representative government and he was to be close to the storm-centre of the tumultuous political events that led to responsible government in 1854. His role in these events was a significant one, not only because the judiciary was so closely involved with the politics of the early assemblies, but also because he held the additional office of clerk of the General Assembly.

Archibald became involved in the quarrel that erupted in January 1833 between the House of Assembly and the Council over the latter’s power to amend revenue bills. He drew up the case for the assembly which, being sustained, led to the resignation of Chief Justice Richard Alexander Tucker*, president of the Council. His clerkship of the assembly being by crown appointment, it was inevitable that Archibald should eventually find it impossible to maintain a balance between loyalty to the executive and to the House of Assembly, both of which he was required to serve. The assembly’s attitude towards Archibald cooled in 1837 when he was compelled to deny to a committee of the whole house access to certain documentary evidence that he had originally promised to produce and that, in its opinion, would have strengthened the case for the dismissal of Chief Justice Henry John Boulton*. The reason for Archibald’s change of mind is apparent in a memorandum addressed to the assembly by Governor Henry Prescott* which stated categorically that “neither Mr. Archibald nor any other public functionary is at liberty to produce documents . . . committed to his charge without direction from the Executive Government.” Although the radical chairman of the committee, John Valentine Nugent*, excused Archibald on the grounds that he was undoubtedly acting upon orders from the chief justice, the house, as a matter of principle, demanded and secured the right thereafter to appoint its own officers. Later that year Archibald’s appointment as clerk of the General Assembly was terminated at his own request because he believed that he would find it impossible to tolerate the decided conflict of interest that would continue to exist.

In 1838 Archibald was again involved, though not directly this time, in a serious quarrel concerning the privileges and prerogatives of the House of Assembly. The culmination of the quarrel was the celebrated Kielley v. Carson case. Archibald assisted Mr Justice George Lilly* in preparing his dissenting opinion to the decision of the Supreme Court in support of the House of Assembly. Lilly’s opinion was upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council which in 1843 reversed the decision and established, finally and authoritatively, the rule respecting the proper powers of colonial assemblies in the following terms: the House of Assembly of Newfoundland was “a local Legislature with every power reasonably necessary for the proper exercise of their functions and duties, but they have not what they have erroneously supposed themselves to possess – the same exclusive privileges which the ancient Law of England has annexed to the House of Parliament.”

Because of Archibald’s assistance to Lilly in 1838, his name was brought to the favourable attention of Lord Glenelg at the Colonial Office, and he thus added to his reputation for acumen and ability. Perhaps as a direct result, Archibald was summoned to appear before the imperial parliament in 1841 to give evidence upon the working of colonial constitutions. At the same time he was invited by the Colonial Office to assist in developing a new constitutional form for the government of Newfoundland that would avoid the seemingly inevitable deadlock between council and assembly which had rendered the 1832 model unworkable. The result was the Amalgamated Legislature, inaugurated in 1842 with Archibald as its chief clerk. Furthermore, in November 1841 he had been elevated to the office of attorney general for the colony, a position which gave him a seat in the Council and which he held concurrently with the office of clerk of the Supreme Court until his retirement and departure from Newfoundland in 1855.

Despite his Presbyterian upbringing, Archibald, while still a young law clerk in Halifax, had recognized the social advantages of regular attendance at the Anglican St Paul’s Church. By 1840 he had become a pillar of the Anglican establishment in St John’s. The position he had now attained in the political and social community of Newfoundland moved him even closer to the centres of conservatism and weakened what little sympathy he had possessed for those who were, with increasing frequency, designated in his correspondence as “rads.” Nevertheless, he did not display that intransigent opposition to the idea of responsible government manifested by some of his colleagues, nor did the assembly ever come to regard him as one of its bitter enemies. Indeed, during the final negotiations of 1854 that led to responsible government, he joined with the Newfoundland colonial secretary, James Crowdy*, in urging and persuading the Council to accept the necessity of a representation bill which the Liberals in the House of Assembly, led by Philip Francis Little*, were determined to pass as the first act of the newly constituted legislature after responsible government.

Earlier in 1854 Archibald, along with William Bickford Row*, had argued in London the Council’s case against responsible government, and the representation bill in particular; Hugh William Hoyles, representing the Central Protestant Committee, also fought the bill in London. It has been suggested, perhaps unkindly, that Archibald had been persuaded to modify his position by the promise of a substantial pension. Possibly he was sufficiently pragmatic to be willing to face the inevitable. In any event, stating that he could not continue to work with the type of radical who would control the executive government of Newfoundland after 1855, he submitted his resignation late in 1854 (effective the next year); he also refused a proffered seat on the bench, accepted his pension and a cb, and returned to the family home at Truro.

Although Archibald had perhaps intended to return to the private practice of law, he did not find the quiet life of a small town congenial. Consequently when he was offered the post of British consul at New York in 1857 he seized the opportunity with alacrity. For the next 26 years he held that position and in 1871 assumed additional responsibilities when he was named consul general for New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. He performed his job skilfully and tactfully, particularly during the Civil War and throughout the heyday of Fenian activity. When he reached the “compulsory” retirement age of 70, Archibald was asked to remain and did so for an additional three years. He asked and was granted permission to retire on 1 Jan. 1883.

With a pension and a kcmg as rewards for his labours, Archibald again sought a quiet retirement, this time in Brighton, England. Once again he was unable to endure the peace and accepted a business appointment in London, but while house-hunting in that city contracted pneumonia and died.

Sir Edward Mortimer Archibald’s correspondence as British consul at New York with reference to negotiations for the renewal of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States is published in Nfld., House of Assembly, Journal, 1866, app.: 787–92. Archibald published a Digest of the laws of Newfoundland . . . (St John’s, 1847; repr. 1924).

PRO, CO 194, 1832–55. Nfld., Blue book, 1832–51; Executive Council, Minutes, 1848–55; House of Assembly, Journal, 1832–55. Newfoundlander, 1833–55. Patriot (St John’s), 1834–55. Public Ledger, 1832–55. E. J. Archibald, Life and letters of Sir Edward Mortimer Archibald, K.C.M.G., C.B.; a memoir of fifty years of service (Toronto, 1924). Gunn, Political hist. of Nfld. Wells, “Struggle for responsible government in Nfld.”

Cite This Article

Leslie Harris, “ARCHIBALD, Sir EDWARD MORTIMER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archibald_edward_mortimer_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archibald_edward_mortimer_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Leslie Harris |

| Title of Article: | ARCHIBALD, Sir EDWARD MORTIMER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |