Source: Link

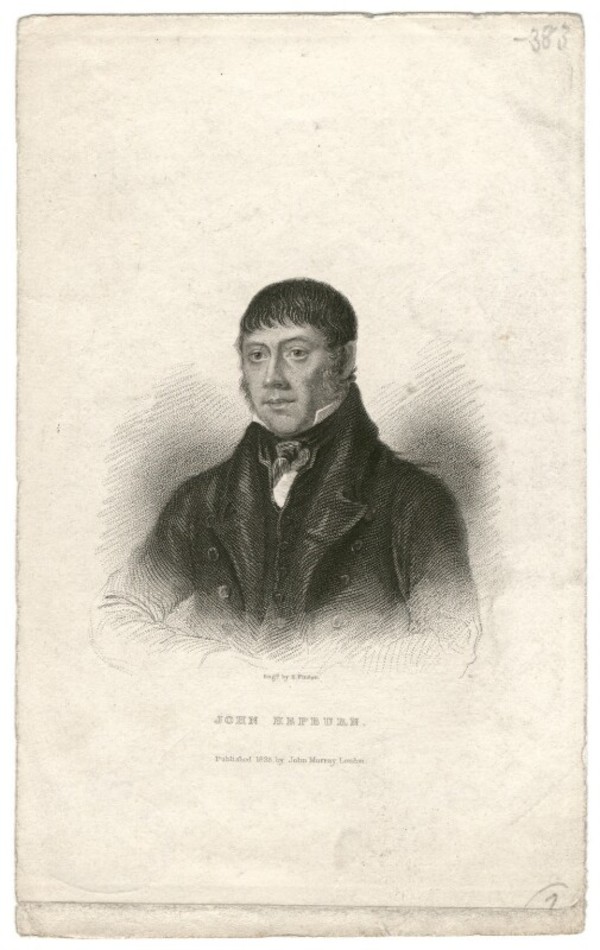

HEPBURN, JOHN, seaman and Arctic traveller; b. in 1794 at Whitekirk, East Lothian, Scotland; d. on 5 April 1864 at Port Elizabeth (South Africa).

After a little education at the local parish school, John Hepburn spent his early years as a cowherd by the Firth of Forth. In about 1810 he became an apprentice seaman, and he spent the next three years sailing between Newcastle and London. At the end of his apprenticeship, he sailed to North America on a trading vessel, and on the return voyage he was shipwrecked, taken prisoner by an American privateer, and later handed over to the Royal Navy. In 1818 he served as able seaman in the navy under Lieutenant John Franklin*’s command on the brig Trent during Captain David Buchan*’s expedition to Spitsbergen. In 1819 he was selected to accompany Franklin, Dr John Richardson, George Back*, and Robert Hood* on an overland expedition to explore the coast eastwards from Coppermine River (Northwest Territories). Although 20 Canadian voyageurs accompanied them, the officers found Hepburn indispensable and by far the most reliable, honest, courageous, and hard working of their subordinates. In 1821, when the party was struggling half-starved from the Arctic coast back to Fort Enterprise, Hepburn, though scarcely any stronger than the rest, tirelessly gathered fuel and the tripe-de-roche that served as food when the others felt too weak to do so. At Fort Enterprise only Hepburn and Richardson found strength to keep searching for food and fuel until help arrived, even though Hepburn’s limbs were then badly swollen.

On their return to England in 1822, Franklin used his good offices at the Admiralty on Hepburn’s behalf. In one recommendation he wrote that Hepburn’s conduct “during a period of extreme difficulty and distress was so humane and excellent as to merit the highest promotion that his situation in life entitles him to . . . .” As a result of Franklin’s efforts, Hepburn was promoted second master in the navy and received a comfortable situation at Leith, Scotland, in charge of a small ship that supplied naval vessels with stores. Later he was made a warder at Haslar Hospital. He remained in contact with Franklin: mutual respect and the common experience of hardship had given rise to a warm friendship between the humble seaman and his chief. When, in August 1836, Franklin became lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), Hepburn sailed with him. He had, by this time, married, but no details of his marriage are known.

In Van Diemen’s Land he first served as superintendent of government house, then as superintendent of the Point Puer convict establishment for boys. Franklin returned to England in 1844, but Hepburn seems to have remained until about 1850. The search for Franklin’s missing northwest passage expedition was at its height on his return. Lady Franklin [Jane Griffin*] insisted he take part in her second Prince Albert searching expedition: “You must not attempt to say (for I know you always think humbly of your merits) that you are not competent, for we all believe & know that you are.” But Hepburn needed no persuading and answered that “there is no employment on earth I should prefer to the forwarding of your amiable views, and I will most readily strain every nerve in my search of my worthy Chief.”

Prince Albert, commanded by William Kennedy* and with Hepburn as supercargo, sailed north from Aberdeen on 22 May 1851, and wintered at Batty Bay, Somerset Island. Hepburn had hoped to lead one of the sledging parties in spring 1852 but his health was not equal to the task. His services were therefore rather limited, but he nonetheless won the trust and admiration both of Kennedy and of Joseph-René Bellot*, the second in command. Kennedy gave Hepburn charge of the ship when the sledging parties were out, and Bellot loved to listen to Hepburn’s yarns about his earlier days with Franklin.

After the expedition’s return home in autumn 1852, Hepburn remained for some years in Britain. Anxious about his health, which had been poor since the expedition of 1819–22 and was further shaken by the second Arctic voyage, he went to the Cape of Good Hope early in 1856 to take up a government appointment. He was ill for many months before his death in 1864.

Of all the hundreds of ordinary seamen who served in the Canadian Arctic during the 19th century, Hepburn was undoubtedly the best known. He was a simple man with little education, yet he won the love and respect of many who were far above his station in life. Franklin’s devotion to him is amply illustrated; Lady Franklin, Richardson, Kennedy, Bellot, and others wrote of him with admiration and affection. It was not only courage and endurance in the field that won him such respect. He was humble and almost excessively modest: in Van Diemen’s Land, he was rather embarrassed by his elevated status and by Franklin’s ambitions for him, and Richardson wrote in 1851: “he always spoke of himself with much diffidence.” But, above all, Hepburn’s unfailing loyalty and devotion to Franklin commanded admiration. His return to the Canadian Arctic in his old age, “as the best tribute he can render, of his affection for his old commander,” was indeed a touching sequel to their long friendship.

Scott Polar Research Institute (Cambridge, Eng.), ms 248/106 (letters and notes of Lady Franklin and Sophia Cracroft, January–March 1851), pp.246, 251–53, 269;

Cite This Article

Clive A. Holland, “HEPBURN, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hepburn_john_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hepburn_john_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clive A. Holland |

| Title of Article: | HEPBURN, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | September 4, 2024 |