BRILLANT, JEAN (baptized Jean-Baptiste-Arthur), telegraph operator and army officer; b. 15 March 1890 in Assemetquagan (Routhierville), Que., son of Joseph Brillant, a railway maintenance worker, and Rose-de-Lima Raiche; d. 10 Aug. 1918 in France.

Born in a tranquil village with an Algonkin name in the Matapédia valley, Jean Brillant seemed destined for a quiet and uneventful existence. Things turned out otherwise, however, for his life proved short and full of action, and came to a sudden end on the battlefield. The military always had a certain attraction for the Brillants. The family in Canada were descended from Olivier Morel* de La Durantaye, who came to New France with the Régiment de Carignan-Salières and was an outstanding officer. Jean Brillant’s great-grandfather Henri de Boisbrillant de La Durantaye served as a lieutenant in the 1st Battalion of Cornwallis, and a great-uncle, Octave de Boisbrillant, was an ensign in the 1st Battalion of Rimouski militia. Jean’s elder brother, Jules-André*, was a prominent businessman, member of the Legislative Council, and honorary colonel of the Fusiliers du Saint-Laurent.

Jean Brillant was still young when he volunteered for service with the 89th (Temiscouata and Rimouski) Regiment (from 1920 the Fusiliers du Saint-Laurent). In 1916, eager to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force, he apparently declared he had already served 13 years with this unit. At that time he held the rank of lieutenant. According to Léopold Lamontagne, the historian of the 89th, Brillant had studied at the College of St Joseph in Memramcook, N.B., and then at the Séminaire de Rimouski in 1904–5. He later worked as a telegraph operator for a railway.

For Lieutenant Brillant, 1916 was a turning-point. During the previous year the 22nd Battalion, which was the only French Canadian infantry unit to serve on the battlefield in World War I, had suffered heavy losses and it urgently required reinforcements. Major Philippe-Auguste Piuze believed he could help meet this need by raising a battalion himself in the lower St Lawrence and Gaspé region, which he knew well since he had lived and worked there. Like a number of other people with similar ambitions [see Onésime Readman], he asked the minister of militia and defence, Sir Samuel Hughes*, for authorization, which was granted on 10 Jan. 1916. Thus Piuze set out to organize the 189th Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He appealed to the 89th Regiment, with which he had served, and Brillant, who was still with it, decided to go with him.

On 20 March 1916 Brillant left his job as a telegrapher. After about six months’ training in Valcartier, he embarked for England with the 189th on 27 Sept. 1916; on 6 October, the day his unit disembarked in Liverpool, he was assigned to the 69th Infantry Battalion. He left for France on 27 October and there he joined the 22nd Battalion, which was bringing its ranks up to strength and reorganizing at Bully-Grenay.

The winter following Brillant’s arrival at the front was quite calm. The 2nd Division, which included the 22nd, remained opposite Liévin, in northeastern France, where the German army undertook no significant moves. The allies did make a few small advances here and there, but that was about all. Brillant had to spend long hours and weeks in muddy, insalubrious trenches which made life miserable. On 12 Dec. 1916 in a letter to his family he confided in a matter-of-fact way, “I’ve been in the trenches for a month and a half; we can’t wait to see the Boches.” Three days later he noted, “Our front is frustratingly quiet.” In March 1917 he complained, “It isn’t always much fun to spend a whole night without moving when the weather is cold and damp, but nobody as yet notices these things. What makes me suffer even more is to go for a long time without taking my boots off.” Indeed, the greater part of 1917 seems to have been rather disappointing for Brillant. From 9 to 14 April 1917 he took part in the attack on Vimy Ridge, but a few days later he had to be hospitalized. On 20 April he wrote to his father: “I’m in the hospital with trench fever. I hasten to add that this disease is nothing to be alarmed about, a little fever and a great weariness in the legs, which sometimes makes it impossible to walk.” He also had the opportunity to take a course and to visit Calais, Boulogne-sur-Mer, and Paris, but he was back in hospital in July, this time at Étaples, south of Boulogne, with a more serious ailment. He did not return to his unit until 19 September, after an absence of two months.

But 1918 was very different from the first full year Brillant had spent in France. The war had begun to show him its true face. He had already lived through some painful experiences and was expecting more. On 1 May he wrote to an uncle: “We are busier and busier. Great things are in preparation for the near future. What blood and suffering this terrible war costs. There may be a certain pleasure in the soldier’s art, capturing a long-desired objective, working out tactics, but these considerations always go hand in hand with pain and tears.” Less than a month later, during the night of 27–28 May, when he was in the vicinity of Boiry-Becquerelle about 110 miles north of Paris, Brillant was called to help silence an outpost defended by two machine-guns and about 50 men. Leading a group of volunteers, he charged the enemy position, cut through the barbed wire protecting it, and, under heavy fire, continued his advance. Within reach of his objective, he noticed a handful of men trying to escape. He set out in pursuit, caught up with them, put four out of action himself, and captured a fifth, who was brought back to the battalion’s lines and provided valuable information. Remaining in action that day despite his wounds, Brillant would be awarded the Military Cross for bravery on 16 Sept. 1918.

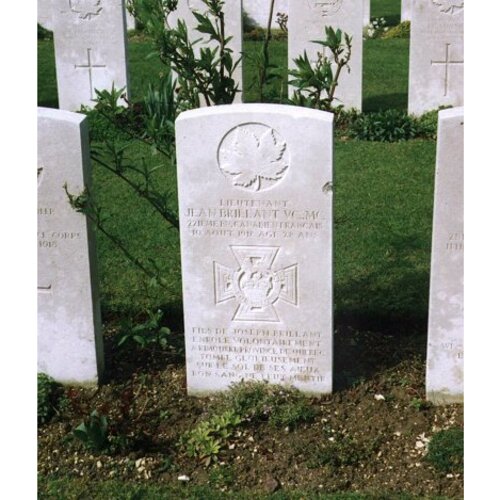

The battle of Amiens in August gave Brillant another chance to distinguish himself. On 8 August, as the advance began, he saw a machine-gun holding up his company’s left flank; he rushed and captured it himself and killed two machine-gunners. Although his left arm was injured, he refused to be evacuated and he returned to action the next day. Commanding two platoons in a skirmish with bayonets and grenades, he took 15 machine-guns and 150 prisoners. This time he was wounded in the head, but he again refused to leave his company and was soon leading a charge against a four-inch field gun firing point-blank on his unit. Hit in the abdomen by shrapnel, he persisted to the best of his ability in advancing towards his objective until, exhausted, he finally collapsed, never to rise again. For a few hours he clung to life in a field hospital, but he died the next day, 10 Aug. 1918. He was only 28. “For most conspicuous bravery and outstanding devotion to duty,” on 27 September he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest British decoration. His remains lie in the Australian military cemetery at Villers-Bretonneux, east of Amiens.

The name of Lieutenant Jean Brillant is kept alive in various ways and many places: he is commemorated at Quebec in the museum of the Royal 22nd Regiment, in Montreal by the Parc Jean-Brillant, in Valcartier at the Canadian Forces Base, and also in Rimouski, Sainte-Foy, and a number of publications. With Corporal Joseph Kaeble, whose life was like his, Brillant stands as one of the most illustrious Canadian soldiers of World War I.

ANQ-BSLGIM, CE1-28, 18 mars 1890. Arch. de la Régie du Royal 22e Régiment (Québec), Dossiers hist. du personnel, 7105 (Jean Brillant). NA, RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 1069. London Gazette, 16, 27 Sept. 1918. Le Progrès du Golfe (Rimouski, Qué.), 20 déc. 1918, 15 févr. 1935. L’Amicale du 22e Inc. (Québec), 1 (1947), no.9: 3; 2 (1948), no.8: 11; 4 (1950), no.10: 46; 7 (1953), no.5: 13; 8 (1954), no.10: 21; 9 (1955), no.11: 7; 10 (1956), no.3: 2; 18 (1964), no.11: 5; no.12: 14. Le capitaine Jean Brillant, c.v., c.m. (Rimouski, 1920). Joseph Chaballe, Histoire du 22e bataillon canadien-français . . . (Montréal, 1952). La Citadelle (Québec), 10 (1974), no.4: 3. “Commémoraison de Vimy; remise d’un drapeau et dévoilement d’une plaque à Jean Brillant, v.c., m.c.,” La Citadelle, 25 (1989), no.1: 12–13. J.-P. Gagnon, Le 22e bataillon (canadien-français), 1914–1919; étude socio-militaire (Québec et Ottawa, 1986). Léopold Lamontagne, Les archives régimentaires des Fusiliers du Saint-Laurent (Rimouski, 1943), 143–46. G. C. Machum, Canada’s V.C.’s; the story of Canadians who have been awarded the Victoria Cross . . . (Toronto, 1956). Nicholson, CEF. J. G. Scott, “Uncommon valour: Canadian winners of the Victoria Cross,” Then and Now (Ottawa), 4 (1994), no.4: 30–31. Valiant men: Canada’s Victoria Cross and George Cross winners, ed. John Swettenham (Toronto, 1973).

Cite This Article

Jacques Castonguay, “BRILLANT, JEAN (baptized Jean-Baptiste-Arthur),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brillant_jean_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brillant_jean_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Castonguay |

| Title of Article: | BRILLANT, JEAN (baptized Jean-Baptiste-Arthur) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |