Source: Link

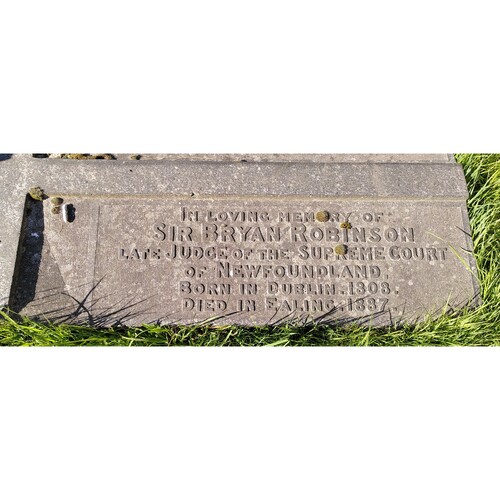

ROBINSON, Sir BRYAN, lawyer, politician, office-holder, and judge; b. 14 Jan. 1808 in Dublin (Republic of Ireland), youngest son of the Reverend Christopher Robinson, rector of Granard, County Longford, and Elizabeth Langrishe, daughter of a prominent Irish politician; m. 20 Aug. 1834 in London, England, Selina Brooking, and they had at least four daughters and one son; d. 6 Dec. 1887 in Ealing (now part of Greater London).

Bryan Robinson attended school in Castleknock, County Dublin, and entered Trinity College, Dublin, in October 1824. He left in 1828 before graduating and joined the staff of Admiral Thomas John Cochrane*, governor of Newfoundland. He was soon appointed sheriff of the Labrador coast, where his brother Hercules had served as a naval officer. On 4 May 1831 in Halifax he was admitted to practise as a barrister and attorney and at 23 began a legal career in Newfoundland that would span half a century. By March 1834 Robinson had been appointed master in chancery to the Legislative Council at St John’s. In this newly created post, he would serve as a link with the assembly, give legal advice, and draft bills until 1858, except from 1842 to 1848 during the life of the Amalgamated Legislature.

Robinson attained prominence in August 1838 as a result of an altercation between assemblyman John Kent* and surgeon Edward Kielley* outside the house. Brought before the assembly on a speaker’s warrant for having allegedly committed a breach of its privileges, Kielley was arrested for contempt, and retained Robinson as counsel. Robinson believed the issue was whether there was “a body of men in this colony who are above the law” and contended that the power claimed by the six-year-old assembly was unwarranted, needless, and contrary to common law. When Judge George Lilly*, finding Robinson’s arguments “learned and very able,” discharged Kielley, the assembly took the unprecedented step of having both Lilly and the sheriff put under arrest. Robinson then, on behalf of Kielley, sued Speaker William Carson*, Kent, and other assemblymen for £3,000 for assault and false imprisonment. The judgement, delivered by the Supreme Court judges before a crowded court-room on 29 Dec. 1838, relied on the exercise of similar powers to commit for contempt by the other British North American assemblies and went against Kielley.

The case of Kielley v. Carson aroused wide concern. The largely Protestant mercantile community in St John’s, mindful that the assembly had succeeded in having Chief Justice Henry John Boulton* removed from office in August of that year, was alarmed at the attack on Kielley and on the judiciary’s independence; it was already extremely concerned at the influence exerted by the Roman Catholic clergy in political affairs [see Edward Troy*]. During the trial Robinson had claimed that if the assembly’s position was upheld, its direct interference in the courts was clearly to be feared. The St John’s Chamber of Commerce petitioned for government by governor and council; merchants in Liverpool, England, called for troops to be sent; and British newspapers joined those in Newfoundland in taking up the case. With the merchants’ support, Robinson went to London to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. After two hearings the committee delivered on 11 Jan. 1843 a precedent-setting opinion in Robinson’s favour, finding the assembly to be a local legislature with every needed power but lacking the exclusive privileges of the British parliament.

In the mean time, Robinson had won some important cases including in 1838 a libel action against Robert John Parsons, publisher of the Patriot, which had hinged on Parsons’ claim that his publication of an assembly report was privileged and not subject to the courts. In June 1840 Robinson had been appointed, with Hugh Alexander Emerson and Edward Mortimer Archibald, to a commission to study the application of English criminal law to Newfoundland. Its report, which Governor Sir John Harvey* commended for able exposition, was received by the Amalgamated Legislature in March 1843. By this time Robinson had become the member for Fortune Bay, having been successful in the December 1842 elections. Robinson soon roused controversy in the legislature; in 1843 his bill to establish a Protestant and a Roman Catholic college was denounced by non-Anglican Protestants as a Church of England measure and had quickly to be dropped. In addition, Harvey’s proposal to appoint him to the Executive Council “on grounds of his talents, influence, and disposition to serve the government” met with the opposition of Chief Justice John Gervase Hutchinson Bourne*, with whom Robinson was involved in a personal conflict. Robinson had complained to the Colonial Office in February 1843 about Bourne’s prejudiced conduct as a judge and about his ignorance of law. For his part, Bourne alleged that Robinson and James Crowdy* had assisted Harvey financially and in return had received improper financial reward. Robinson refuted the charge to the satisfaction of the Colonial Office and on 8 August entered the council, on which he was to serve for some five years. Bourne, on the other hand, was dismissed from office in May of the following year.

Robinson played an active role in many debates and committees of the legislature. He helped prepare and presented bills for improving the administration of justice and the St John’s police. In 1844 he sought to protect the Newfoundland fisheries from French encroachment through measures severely restricting the export of bait and illicit trade in it. Hence, when the assembly sent a delegation to England in 1857 to have the Fishery Convention with France annulled, he was chosen as the Commercial Society’s delegate and provided useful legal assistance; Britain dropped the convention and pledged herself to respect Newfoundland’s views. Convinced that the colony was “the key to the western world,” Robinson wanted Newfoundland to attain her rightful position among the commercial countries of the world. He took a keen interest in developing steam communications between Newfoundland, Great Britain, and the United States, and in promoting St John’s as a port of call for steamers.

By nature a conservative, Robinson, in the legislature’s debate of February 1846, denounced Kent’s resolutions for responsible government as ambiguous and contradictory. He contended party government was unsuited to Newfoundland: it lacked an aristocracy, an influential press, and the means of communication to modify local forces and “blend the feeling of the country into one general sentiment.” His amendments emphasized the governor’s responsibility to the sovereign for the acts of his government, and the accountability of the executive councillors, as individuals, to the people. Kent’s resolutions, however, carried by one vote.

During the 1840s and the 1850s Robinson also served on the Board of Commissioners of Roads for St John’s (in 1843 and 1851), on the Board of Health for the city (in 1847 and 1849), and as a justice of the peace. Appointed a qc on 13 Dec. 1844 and treasurer of the law society for some years, he served as acting solicitor general in 1845, 1847, and 1849, and acting attorney general in 1854. Through his private practice he became the most prominent barrister in St John’s and in 1849 won an important civil rights case, Hanrahan v. Barron and Doody, which established a fisherman’s right to put a lien for wages on the proceeds of a voyage that had been transferred from the planter to the supplying merchant. This judgement was confirmed by the law officers of the crown in 1850. On 4 July 1858 he was appointed 2nd assistant judge of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland, where he would sit for nearly 20 years.

Robinson’s judicial decisions on a wide variety of property and contract cases reveal his innate conservatism, an understanding of the mercantile community, and a belief in the importance of the rule of law to both persons and commerce. He emphasized the need for the courts to adhere to the principles and precedents of British law. If judges bent “the established rule of law” to meet a personal sense of the hardship of a given transaction, the uncertainty resulting would, he thought, be disastrous in a commercial community; they must “apply the law with a steady hand.” While he denounced the local system of credit as hazardous to merchants, demoralizing to planters, and “pestilent” for the fishermen, he insisted creditors should be “enabled to put the law in force against their debtors where the debtor has property”; otherwise no merchant would be reckless enough to issue supplies. For the peace of society “the rules which govern the disposition of property should be settled, and not fluctuating.” Outrages on property or peace must be firmly met, otherwise “capital and industry would speedily seek a more secure and congenial domicile”; hence he refused bail in the case of the Queen v. Gorman et al., which arose from an electoral riot in Harbour Main in 1860.

As a judge Robinson showed an unquestioned ability to reason from general principles in a wide perspective, taking equity, common sense, and possible consequences into account. A man with a marked spirit of independence, he frequently gave dissenting judgements. His decisions show considerable understanding of people and realities, conciliatoriness, and compassion. He also believed that a judge should play an active role. Accused in 1869 by the attorney general of invading the jury’s province in the trial of Berney v. O’Brien and Company, Robinson replied that one of a judge’s most important functions was “to assist a jury in arriving at a correct conclusion by telling them plainly what are his views respecting the proper inferences to be drawn from given facts.” In the spring of 1870 Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter* and Edward Evans sought court restraint of a house committee appointed to investigate their election. In a judgement with a curiously modern ring, Robinson, ruling against the committee, asserted that Supreme Court judges had a “sacred duty . . . to interpose the shield of the law between public bodies and private individuals whenever judicial power is illegally claimed by the strong over the weak”; he argued that such a tribunal exercising independent authority was essential to secure respect for persons and property and the benefits of British law.

Robinson was appointed in March 1874 chairman of a three-man royal commission of inquiry which had been established by the House of Assembly to investigate the administration of the public accounts in the previous eight years. The propriety of a judge’s serving on such a body was challenged and the commission was denounced by Robert John Pinsent* as likely to be a “political engine.” Its reports, based on broad investigations and carried in part in the Royal Gazette, revealed that certain checks on accounts had been removed and public moneys misappropriated under the previous government of Charles James Fox Bennett. As a result, the government established tighter control of the Board of Works, and the findings were used to help Carter defeat Bennett in the November elections. The following year the assembly put pressure on Robinson to release his notes of the commission’s work. He declined, insisting that evidence had been given neither under oath nor in the knowledge it could be made fully public; he asserted that if a royal commission retroactively assumed such power it could be an “engine of oppression” since it might place the reputations of individuals beyond the courts’ protection. He also stated that the public trusted his impartiality. In November 1874 he had in fact been commended by the governor, Sir Stephen John Hill*, for his assiduity and ability in discharging his duties on the commission.

Robinson always had broad interests in the community and local organizations. He served on the executive of the Benevolent Irish Society several times in the early 1830s, was active for many years in the Newfoundland Church of England Asylum for Widows and Orphans, and took the lead in organizing relief and work for the poor in 1869 after the assembly had discontinued its assistance. A staunch Anglican and warden of the parish of St John’s in 1843, he remained interested in the Newfoundland Church Society for almost 30 years, sometimes serving on its management committee; within it he assisted Bishop Edward Feild*, who became a close friend. He was named to the Protestant Board of Education in 1852, and as a director of the Church of England branch of the St John’s Academy in 1855. Elected for the Cathedral of St John the Baptist, he was a valuable member of the first diocesan synod of Newfoundland in 1873 and was one of the five laymen appointed to the diocesan executive committee. Robinson also took a lively part in St John’s social and intellectual life, sitting on committees to organize celebrations for the completion of the Atlantic cable in 1857 and the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1860. He also gave public lectures to local societies.

Seriously interested in his country’s agricultural development, Robinson served in the Agricultural Society at St John’s for many years and was either its president or vice-president for much of the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. He owned a farm and won prizes for his crops. Under his presidency the society issued in 1850 a pamphlet to promote agriculture in which Robinson expressed high hopes for Newfoundland; he felt that the island, geographically at the same latitude as Canada and France, could and should become self-sufficient in food production and hence he pressed for local agricultural societies and increased assembly grants, to provide good seed, implements, and advice. Late in 1877 Robinson retired to England. Knighted at Windsor Castle on 12 December, he went to live with his daughters at Ealing where he remained active in Anglican concerns, especially the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

Over the years he had received many tributes to his legal ability, impartiality, dedication to duty, and sound judgement. A handsome man with full beard and heavy brows, serious mien, and an air of distinction, Robinson was one of the most polished speakers of the time. Early in his career, he made his name through passionate defence of the liberty of the individual, and, imbued with a strong sense of the heritage of British laws and institutions, he continued to stand up for the civil rights of individuals against unwarranted intrusions by the assembly and bureaucratic bodies. Convinced the courts must protect property and commerce, he also showed special concern for the rights and needs of both the employed and the poor. Robinson devoted his life to fulfilling his vision of Newfoundland as a thriving society with British institutions and a self-reliant economy.

The reports: decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland (St John’s), 2 (1829–45)–6 (1874–84). Novascotian, 5 May 1831. Public Ledger, 1828–77. Royal Gazette (St John’s), 1828–77. Times (London), 13 Dec. 1877, 9 Jan. 1878. Times and General Commercial Gazette (St John’s), 1838–17 Dec. 1877, 4 Jan. 1888. Frederic Boase, Modern English biography . . . (6v., Truro, Eng., 1892–1921; repr. London, 1965), III: 221. DNB. Gunn, Political hist. of Nfld. Prowse, Hist. of Nfld. (1895). Malcolm MacDonell, “The conflict between Sir John Harvey and Chief Justice John Gervase Hutchinson Bourne,” CHA Report, 1956: 45–54.

Cite This Article

Phyllis Creighton, “ROBINSON, Sir BRYAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 5, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robinson_bryan_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robinson_bryan_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phyllis Creighton |

| Title of Article: | ROBINSON, Sir BRYAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 5, 2025 |