Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

McCORMICK, ROBERT, naval surgeon, Arctic explorer, and naturalist; b. 22 July 1800 at Runham, near Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England, the only son of Robert McCormick, rn; d. 25 Oct. 1890 at Wimbledon (now part of Greater London), England.

Robert McCormick spent his childhood near Great Yarmouth and was educated by his mother and sisters. His father, a naval surgeon, had encouraged young Robert to become a naval executive officer, but his death in the wreck of the Defense in December 1817 left his son without the necessary influence and means. In 1821 Robert decided to enter the Royal Navy as a surgeon. He was accepted as an apprentice by the famous Sir Astley Paston Cooper, originally from Norfolk, and after study in London at Guy’s and St Thomas’s hospitals he became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons on 6 Dec. 1822. In 1823, as assistant surgeon, he was assigned to the flagship Queen Charlotte.

McCormick’s first duty was in the Caribbean where he served until 1825 when he contracted yellow fever and was invalided home. He then spent two years as medical officer to shore stations. McCormick’s first experience in the Arctic was in 1827 with William Edward Parry* aboard the Hecla to Spitsbergen, although he was not a member of Parry’s unsuccessful polar sledge party. He contributed significantly to the expedition by keeping the crew healthy and by studying the plants, animals, and geology of Spitsbergen. Following the expedition he was promoted to the rank of surgeon on 27 Nov. 1827.

After a year on half pay, McCormick was assigned to the Hyacinth and Caribbean duty, but in 1830 he was again invalided home, from Rio de Janeiro. Posted once more to the Caribbean, he suffered yet another attack of yellow fever, for which he was sent home in 1834. For the next four years he was unattached except for one month aboard the Terror in relief of ice-bound whalers.

In 1839 McCormick successfully applied for duty with the expedition of James Clark Ross* to the Antarctic as surgeon and zoologist aboard the Terror. The expedition was out from September 1839 until September 1843 and did important work in all branches of science in the Antarctic, Australia, and New Zealand. The large collections of zoological materials were worked up later, however, not by McCormick, but by John Edward Gray and Sir John Richardson*, on orders from the Admiralty after the task had remained undone for some time after the expedition. McCormick apparently lacked the drive and skill, and also the scientific ability, to cope with the massive collections. He did gain some recognition with election in 1844 as an honorary fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. In 1845 McCormick received what he thought was a life appointment as a surgeon to the yacht William and Mary, but to his dismay the commission was changed and he was assigned to the Woolwich Dockyard, east of London. Even in this post he was disappointed; he was superseded in 1849.

McCormick was a proponent of the search for Sir John Franklin*, and was one of the first to lay detailed plans for it before the Admiralty and the House of Commons. He advocated the use of small boats and sledges to explore Wellington Channel and then go south to Boothia Peninsula and King William Island. His suggestions, well based on Arctic and Antarctic experience, were unofficial, coming from a medical officer and not a line officer, and were rejected. (Francis Leopold McClintock* was later to prove him correct.)

In 1851, however, McCormick was appointed surgeon on the North Star in the search fleet of Sir Edward Belcher*; in February 1852 William John Samuel Pullen received the command of the North Star. At last McCormick’s life-long ambition was realized: during this expedition he became officer in command of a party. In August and September 1852 he explored the Wellington Channel, in a boat named Forlorn Hope, covering 240 statute miles. He did not find any trace of Franklin’s ships, Erebus and Terror, but did map the east side of the channel and establish the probability of a connection between Baring Bay and Jones Sound, virtually proving that Franklin had proceeded westward from Beechey Island.

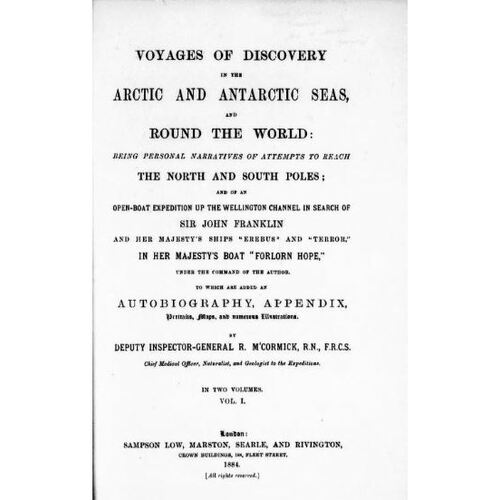

McCormick was awarded the Arctic Medal in 1857. In 1859 he was finally promoted deputy inspector-general, his last rise in rank. He was placed on the retired list in 1865, and in 1876 received a Greenwich Hospital pension of £80 per annum through the good offices of his friend, the medical director-general, Sir Alexander Armstrong*, himself an old Arctic hand. In 1884 McCormick published Voyages of discovery in the Arctic and Antarctic seas, and round the world. Despite excellent illustrations, sound scholarship, and an interesting narrative, it came too late to arouse much interest for most of the information was already well known and the incidents were too remote for acclamation.

McCormick, in fact, spent the last 20 years of his life in relative obscurity. He had failed either to reach the top in the naval medical service or to become a distinguished biologist. He displayed stamina and competence in exploration but had little opportunity to engage in it except, perhaps, during the North Star expedition. His troubles in the Admiralty have been attributed to a lack of tact and a strong individualism which resulted in frequent disagreements with each of the medical directors-general of his time, especially Sir William Burnett. The yellow fever he contracted and his dislike of small ships led him to avoid assignments to the Caribbean, even to the point of insubordination. However, these characteristics do not explain the scientific failure. McCormick was on good terms with many influential scientists of the day, including Sir John Barrow, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, and Sir Charles Lyell, and had opportunities to make his mark, but he did not display the single-mindedness, patience, and learning which in these years gave men like Hooker and Francis Beaufort distinguished careers.

McCormick’s name was given to several natural features: in the Antarctic, to Cape McCormick by Ross; in the Arctic, to McCormick Bay by Beaufort and McCormick Inlet by McClintock; and in northwest Greenland, to a valley. McCormick was proud of having his portrait painted in 1853 by Stephen Pearce, one of a series planned on the commanders in the Franklin search. He thought it a harbinger of a distinguished future, but, in the event, the Forlorn Hope was his first, last, and only command.

Robert McCormick was the author of Narrative of a boat expedition up the Wellington Channel in the year 1852 . . . (London, 1854) and Voyages of discovery in the Arctic and Antarctic seas, and round the world . . . (2v., London, 1884).

PRO, ADM 11/104. H. Berkeley, “Naval biography: Deputy Inspector-General Robert McCormick, R.N., F.R.G.S.,” Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine (London), new ser., 1 (1889): 607–11. Frederic Boase, Modern English biography . . . (6v., Truro, Eng., 1892–1921; repr. London, 1965), II: 576. DNB. [V. G. Plarr], Plarr’s lives of the fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, ed. D’Arcy Power et al. (2v., Bristol, Eng., and London, 1930), I: 100. Arctic Pilot (London), III (5th ed., 1959): 295, 575, 595, 631. J. J. Keevil, “Robert McCormick, R.N., the stormy petrel of naval medicine,” Royal Naval Medical Service, Journal (London), 29 (1943): 36–62.

Cite This Article

Robert E. Johnson, “McCORMICK, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccormick_robert_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccormick_robert_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert E. Johnson |

| Title of Article: | McCORMICK, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |