Source: Link

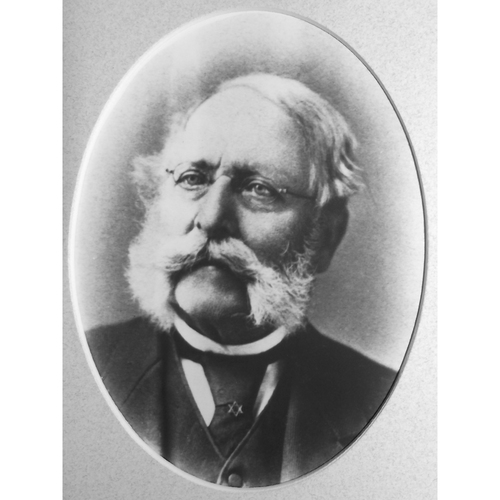

BOTSFORD, BLISS, lawyer, landowner, politician, and judge; b. 26 Nov. 1813 at Sackville, N.B., the seventh son of William Botsford*, a politician and judge, and Sarah Lowell Murray, née Hazen; m. in 1842 Jane Chapman, and they had five children; d. 5 April 1890 at Moncton, N.B .

Bliss Botsford was the grandson of both Amos Botsford*, a distinguished loyalist who served as speaker of the New Brunswick House of Assembly from its inception in 1786 until his death in 1812, and William Hazen*, a prominent pre-loyalist merchant. Little is known of Botsford’s childhood or early education; in 1829 he entered King’s College (University of New Brunswick) in Fredericton and later left without taking a degree. Following in his father’s footsteps, he studied law, under William End* of Gloucester County, and in 1838 was admitted to the bar. In 1836 Botsford moved to the Bend of Petitcodiac (Moncton) where he practised until 1870. When he arrived at the Bend it consisted of a few small shops, an inn, and less than 20 dwellings surrounded by marsh and forest. Botsford established for himself a large home with extensive grounds in the centre of the village, and as the settlement grew he began to acquire lands through purchase, mortgage, settlement of estates, and court judgements. In 1854, for example, he was assigned 100 acres of prime real estate in the town in payment of debts owed him by Jacob Trites, a grandson of the original land grantee. When the Anglican parish was established in 1851 Botsford donated land for the church and rectory and became one of the first church wardens.

Moncton, incorporated as a town in 1855, had expanded rapidly after 1850, chiefly because its shipbuilding industry was responding to the great demand for vessels caused by the Crimean War and the Australian gold-rush. By the late 1850s, however, the market for ships in Liverpool, England, was glutted and the operations of Joseph Salter, Moncton’s leading shipbuilder, were ruined in 1859. No new industry was found to replace shipbuilding, the Westmorland Bank (which was to fail in 1866) showed signs of weakness, real estate values dropped drastically, and the town debt could not be retired because many citizens were unable to pay their taxes. The completion in 1860 of the European and North American Railway from Saint John to Shediac did not offset these adverse economic factors, and the town settled into a deep depression. When Botsford was elected mayor of Moncton in March 1862 he successfully petitioned the legislature to repeal the town’s incorporation act, thus reducing expenses by eliminating salaries for town officers and spreading the tax load among citizens over the whole of Westmorland County. Moncton was not to be reincorporated as a town until 1875, when its growing importance as a railway centre caused a resurgence. In 1870 the federal cabinet approved the recommendation of the commissioners of the Intercolonial Railway that Moncton be the site of the principal workshops of the publicly owned line. The city was also the junction-point of the Intercolonial and the European and North American Railway. Despite the national depression of the 1870s, railway activity at Moncton spurred further growth.

Botsford had been an active participant in Moncton’s changing fortunes on the provincial as well as the local level. From 1851 to 1854 and again from 1856 to 1861 he had been a member of the assembly for Westmorland County, but he did not distinguish himself in the legislature. In 1865 he declared himself an opponent of New Brunswick’s entry into confederation, and after his election in March of that year he became surveyor general in the anti-confederate government of Albert James Smith. The following year Smith’s government was defeated at the polls, but Botsford was personally re-elected and from 1867 to 1870 served as speaker of the New Brunswick assembly, a post previously held by both his father and his grandfather.

Botsford’s impressive figure, well over six feet in height and more than 200 lbs in weight, coupled with personal magnetism and a vigorous and persuasive style of delivery, won for him a high place in the ranks of the legal profession. His greatest case was in 1852 when he represented Peter and John Duffy against Dr Abraham Gesner*, the celebrated geologist. On land 16 miles south of Moncton, the mineral and mining rights to which the Duffys had acquired and had then assigned to William Cairns, Gesner had discovered an outcropping of a glossy black substance with a high gas content which resembled soft coal. He called it albertite, but the Duffys claimed that the mineral was true coal and that, because of certain provincial regulations, it belonged to them. Gesner, supported by several scientists from Canada and the United States, claimed that the mineral was a new substance and that ownership was his by right of discovery. Botsford’s defence included the use of expert testimony and a strong appeal to the principle of the “right of property owners,” an argument which induced the jury to decide in favour of his clients. However, further research in later years proved that Gesner’s argument had been correct.

By 1870 Botsford was one of Moncton’s most respected citizens, and he was known for his hospitality. He was also an active freemason, and in 1870 the Royal Arch Masons named their new chapter after him. In the same year he was appointed judge of the county court for Westmorland and Albert, a post he held until his death. He was respected as a judge for his fairness, sympathetic treatment of young lawyers, logical and concise charges to juries, and the firmness of his decisions.

On 5 April 1890 Botsford was leaving his club rooms, located on the second floor of a building on Main Street, when he collapsed on the stairs and fell through a large window to the board sidewalk below. He died of massive fractures and internal haemorrhages a few hours later. On the day of Botsford’s funeral, official mourning was declared in Moncton, which was to be incorporated as a city just two weeks later.

St George’s Anglican Church (Moncton, N.B. ), “History of St George’s Anglican parish,” comp. J. J. Alexander (typescript, 1932). PANB, “This New Brunswick, a parade of places and people,” comp. Ian Sclanders (clippings from the Telegraph-Journal, Saint John, N.B., 1937–38). Westmorland County Registry Office (Dorchester, N.B.), libro GG: 536–38. Moncton Times, 20 Jan. 1885, 11 Dec. 1889, 7, 9 April 1890, 15 June 1927. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1888), 603. The register: being a list of former students and graduates of the College of New Brunswick, later King’s College, and since 1859 the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, N.B. (Fredericton, 1924). E. W. Larracey, The first hundred: a story of the first 100 years of Moncton’s existence after the arrival in 1766 of the pioneer settlers from Philadelphia, Pa. (Moncton, 1970), 122–23. L. A. Machum, A history of Moncton, town and city, 1855–1965 (Moncton, 1965), 43, 107. MacNutt, New Brunswick, 432. C. A. Pincombe, “The history of Monckton Township (ca. 1700–1875)” (ma thesis, Univ. of New Brunswick, Fredericton, 1969), 141, 152, 167–68, 206–8. Waite, Life and times of confederation, 247. J. C. Webster, A history of Shediac, New Brunswick ([Shediac], 1928), 13.

Cite This Article

C. Alexander Pincombe, “BOTSFORD, BLISS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/botsford_bliss_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/botsford_bliss_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. Alexander Pincombe |

| Title of Article: | BOTSFORD, BLISS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |