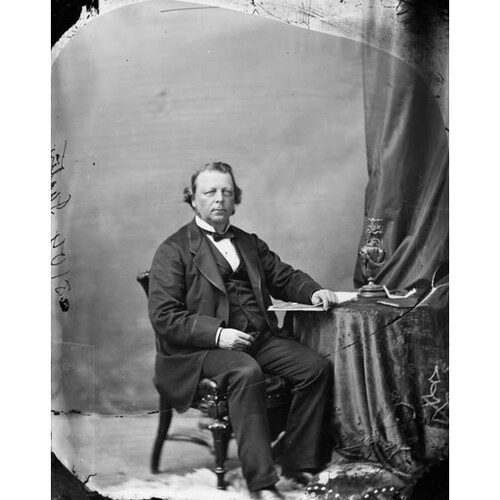

FOSTER, ASA BELKNAP, railway contractor and politician; b. at Newfane, Vermont, 21 April 1817, son of Stephen Sewell Foster*, a physician and politician, and Sally Belknap; d. at Montreal, Que., 1 Nov. 1877.

Asa Belknap Foster came with his parents to Frost (near Waterloo, Lower Canada), in 1822 and was educated in the village. In 1837 he returned to the United States where he joined his uncle, S. K. Belknap, a railway contractor, and for 15 years built railways in New England. He married Elizabeth Fish of Hatley, Lower Canada, in 1840; they had ten children.

Foster returned to Canada in 1852 and settled in Waterloo. He became both a merchant and an immensely successful contractor, building railways throughout Quebec and bordering areas. Foster served as president of the South Eastern Counties Junction Railway (later the South Eastern Railway), vice-president and managing director of the Canada Central Railway, managing director of the Brockville and Ottawa Railway, and director of the Bedford District Bank, and he attained prominence in Montreal business circles.

Foster entered politics in 1858 as a follower of George-Étienne Cartier when he was elected in a by-election to the Legislative Assembly for Shefford. He had received the support of Lucius Seth Huntington*, a Liberal, both of them being opposed to the custom of non-resident members in the Eastern Townships. Huntington was elected for Shefford when Foster resigned in 1860 to run for the Legislative Council. Acclaimed for Bedford, Foster held the seat until 1867 when he entered the dominion Senate. Also in 1867 he was chosen the first mayor of the municipality of Waterloo, and from 1857 to 1869 was a lieutenant-colonel in the Shefford militia.

Foster was involved in the “Pacific Scandal,” partly through his friend, George W. McMullen, the Canadian-born businessman from Chicago. McMullen, acting for a group of American businessmen bitter over their exclusion from the transcontinental railway company being formed in Canada in 1872, attempted to redeem some of the money they had advanced through Sir Hugh Allan* to the Conservatives (including Sir John A. Macdonald* and Cartier) during the 1872 election. The expedient tried was blackmail: on 31 Dec. 1872, McMullen visited Macdonald and demanded business concessions connected with the railway in exchange for not publishing incriminating documents concerning the 1872 campaign. Macdonald refused. Charges of corruption based on the documents were soon after made in the House of Commons by Huntington and the documents were later published.

Foster had been aware of the dealings between Allan and Macdonald and Cartier in 1872, and revealed this knowledge in a letter meant for publication which he wrote to McMullen, who was being much abused, in July 1873. The angry Conservatives assumed that it was Foster who gave McMullen’s evidence, which helped to destroy Macdonald’s government, to his friend Huntington and the Liberals. Foster, a provisional director of Allan’s Canada Pacific Railway, refused to testify – as did the Liberals – before the royal commission investigating the scandal.

Belief in the apostacy of the Conservative senator was intensified by two agreements made by the new Liberal government under Alexander Mackenzie* in 1874 and 1875 under the authority of the Canadian Pacific Railway act of 1874. The first agreement, with the Canada Central Railway of which Foster was a leading figure, provided a subsidy of $12,000 per mile for the construction of the link between the village of Douglas, near Renfrew, Ontario, and the Georgian Bay branch of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The latter was to be constructed, under the second agreement, from Lake Nipissing to Georgian Bay. Although it was to “be considered as forming part of the Canadian Pacific Railway,” it would “upon its completion be the property of the Contractor. . .”; the subsidy per mile was $10,000 and 20,000 acres of land. Senator Foster thus contracted to build and operate some 200 miles of line, from the C.P.R. terminus at Lake Nipissing to Georgian Bay as well as into the Ottawa valley. According to Alexander Mackenzie these lines would provide “the most direct line from . . . Georgian Bay to Montreal . . . .” Provision was made for cooperation between Foster’s system and such north-south lines as the Northern Colonization Railway (which formed part of the Canada Central Railway) and the Kingston and Pembroke Railway. Foster had earned the epithet: “Canadian Railway King.”

The Conservatives were convinced that these railway transactions were venal. Senator Robert Read charged: “Now what is this for? Simply to pay the Northern Pacific [to which McMullen was connected] for their assistance through McMullen to defeat the late Government, and also Mr. Foster for the part he took in that transaction.” According to J. G. Haggart*: “It was a notorious fact that the information used to turn out the late Government was furnished by the Hon. A. B. Foster, and everybody in the country expected that [he] would receive his reward . . . And he did.”

By the mid-1870s Foster was in financial trouble. In 1871 he had purchased major portions of the Brockville and Ottawa Railroad and of the Canada Central. He also bought a huge quantity of rails. His debt of $2,000,000 was to be paid in instalments, but by 1877 he was bankrupt, and at the insistence of the American competitors of his South Eastern line in Vermont he was briefly imprisoned in Vermont for debt. So vicious was competition, that in 1877 parts of that line were sabotaged and had to be “guarded by a sheriff and posse.” The bankrupt promoter died of heart disease at Montreal. He had resigned his seat in the Senate in 1875, ending an undistinguished legislative career.

The Montreal Gazette commented: “He devoted himself to the construction of railways with an ardor which did not spring from any mere desire of pecuniary profit, but from enthusiasm in his profession.” This assessment can be faulted without accepting the strictures of the Conservatives. Nineteenth-century railway promotion in Canada reveals little selfless idealism; David Mills* pointed out that “Corruption taints the majority of railroad enterprises from their inception to completion.” Evidence in this area concerning Asa Belknap Foster is both documentary and circumstantial; he sometimes used the aphorism: “It is no good having friends if you can’t use them.” He was doubtless not an untypical railway man, although his career juxtaposes failure and success in an unusually dramatic manner.

PAC, MG 26, A (Macdonald papers), 125. Canada, House of Commons, Debates, 1877; Sessional Papers, VIII (1875), pt.8, no.44. Gazette (Montreal), 1877. Globe (Toronto), 1873, 1877. Montreal Witness, 1877. Can. biog. dict., II, 75–76. Can. directory of parliament (Johnson). Can. parl. comp., 1873. Dom. ann. reg., 1878. Creighton, Macdonald, old chieftain. H. A. Innis, A history of the Canadian Pacific Railway (Toronto, 1923; Toronto, 1971). Gustavus Myers, History of Canadian wealth (Chicago, 1914). J. P. Noyes, Sketches of some early Shefford pioneers ([Montreal], 1905), 7–90.

Cite This Article

Donald Swainson, “FOSTER, ASA BELKNAP,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/foster_asa_belknap_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/foster_asa_belknap_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald Swainson |

| Title of Article: | FOSTER, ASA BELKNAP |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |