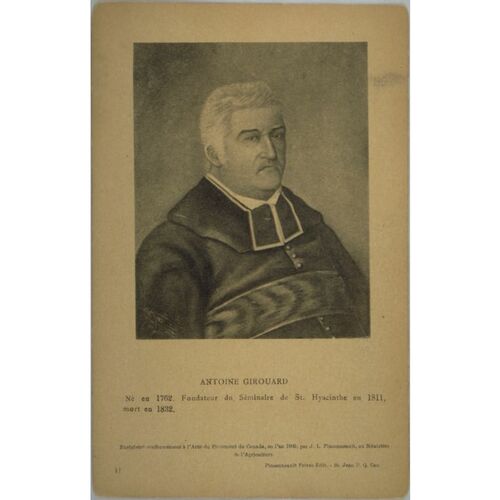

GIROUARD, ANTOINE, Roman Catholic priest and educational administrator; b. 7 Oct. 1762 in Boucherville (Que.), son of Antoine Girouard and Marguerite Chaperon; d. 3 Aug. 1832 in Varennes, Lower Canada.

Antoine Girouard, whose father had died before he was born, was a good student, first at the Collège Saint-Raphaël in Montreal from 1773 to 1780, and then in theological studies at the Grand Séminaire de Québec. He was ordained priest by the bishop of Quebec, Louis-Philippe Mariauchau* d’Esgly, in the autumn of 1785. The bishop almost immediately sent him as a missionary to the Baie des Chaleurs region. This first ministry south of the bay brought him into contact with Acadian fishermen and Indians. In the autumn of 1790 he was named parish priest of Saint-Enfant-Jésus (in Montreal) and was given responsibility as well for Saint-François-d’Assise (also in Montreal).

In September 1805 Girouard became parish priest of Saint-Hyacinthe, replacing Pierre Picard. He was 42, and had some savings. The Saint-Hyacinthe region, where the Rivière Yamaska had been settled more recently than the shores of the St Lawrence and the Richelieu, was then entering a period of rapid development. Girouard’s parish had been established in 1777 but had only acquired a resident curé in 1783; it was huge, extending to the upper reaches of the Yamaska and even into the Eastern Townships. A stone church had been built a few years earlier, to which Girouard would add a large presbytery.

But Girouard had other ideas in mind as well, specifically a plan to found a classical college. Existing institutions in Lower Canada were the Séminaire de Québec, the Collège Saint-Raphaël, and, since 1803, the Séminaire de Nicolet. The parish priest of Saint-Denis on the Richelieu, François Cherrier*, set up a boys’ school with a boarding establishment in 1805, but it lasted only a few years. By 1809 Girouard was asking Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis to send him a Latin teacher. Classes were held in the sacristy, and later in the parishioners’ room in the presbytery. Girouard soon tried to persuade the bishop that a building should be put up. He believed the need existed, and he had the essential resources, the support of local seigneurs, and the access to voluntary labour for transporting materials. At first Plessis thought premature competition would be created with the Séminaire de Nicolet, which still had to secure. the teachers, pupils, and conditions that would permit it to make ends meet. But Girouard insisted, wrote letter upon letter, particularly in 1810, and late that year Plessis gave in to his pleas. He was given permission to build, although he was to proceed gradually and bear in mind the establishment at Nicolet.

The site of the college, in the village of Saint-Hyacinthe, was given to Girouard in 1810 by seigneurs Hyacinthe-Marie Simon, dit Delorme, Pierre-Dominique Debartzch*, and Claude Dénéchaud*. In addition Girouard bought land which provided wood and hay and could one day be developed for the benefit of the college. For a few years the parish priest became an entrepreneur, buying materials and even overseeing work in progress. Sometimes he secured exemption from seigneurial dues. A few donations were obtained from priestly friends. He was able to buy cheaply the house that had been built by Picard, and he considered putting the pupils in it temporarily but had to rent it to the army during the War of 1812. Throughout this period the college was being built on plans drawn up by Abbé Pierre Conefroy*. It was completed in 1816 and comprised a main building 88 feet by 50 with three storeys, and two wings 24 feet square of the same height as the main building. In 1816 also, Girouard, who for some years had wanted to encourage the founding of a girls’ boarding-school, welcomed into the Maison Picard the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, who opened a school in it in August.

In 1818 Girouard requested a principal be named for the classical college, and Joseph-Philippe Lefrançois was appointed the following year. Although freed from officially directing the institution, Girouard remained its owner, and since there was no bursar, he carried out most of the administrative tasks until 1826. The few grants given by the government were made out to him. In such matters as the appointment of teachers or disciplinary rules for the pupils, the principal and the founder were rather strictly subject to ecclesiastical authority. The general direction of the college was thus defined through a shifting balance among the bishop, the principal appointed by him, and Girouard. Girouard had several advantages: unlike the bishop, he had some experience of the local situation and unlike the principal he had a permanent position. There were six principals in succession in the period 1819–31.

The college had its ups and downs but nevertheless expanded. In 1822 it had about 50 boarders, as many day pupils, and a staff of nine teachers and regents. But when in 1824 authority over the parish and the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe was transferred from Quebec to Montreal, at the time the diocese of Montreal was taking shape, Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue* asked the college to limit itself to teaching the lower forms. Girouard, who saw his project threatened just as it was growing rapidly, respectfully refused. The college first admitted pupils to every year of the classical program in 1826.

In his work as an educator Girouard thought he had “many enemies, even within the clergy,” and at the same time “many friends, even among the laity” and “among those most enlightened.” He was especially proud of being able to count on the financial and moral support of an association for improving educational opportunities in the Rivière Chambly area, which had been formed in 1821 on the initiative of Charles de Saint-Ours; with 21 members, including Plessis, the organization over a period of eight years gave the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe the funds to educate some 30 pupils. Its goal was to help “children of worthy habitants chosen and recommended by the parish priests” to become “either priests or well-educated citizens . . . two aims advantageous to the country.”

As priest, Girouard was also in charge of a large parish. Although its territory had been reduced by the formation of three other separate parishes – Saint-Damase in 1817, Saint-Césaire in 1822, and Saint-Pie in 1828 – his parish had 3,792 inhabitants in 1831, 1,100 of them in the village itself. Girouard seems to have resigned himself to the creation of these new parishes. For example, in the case of Saint-Pie he was willing to contribute lands of which he was the owner, but he insisted on keeping a wooded property so its yield could be used by the college.

Girouard’s relations with the family of Saint-Hyacinthe’s seigneurs apparently were cordial. Before becoming seigneur in 1814, Jean Dessaulles had been the seigneurial agent, and in this capacity he had dealt with the original gift of land for the college. In 1820, when writing to Joseph Papineau* in Montreal to order wine, Girouard suggested that it could be delivered to him through Dessaulles’s good offices. The seigneur and the parish priest were among those elected in 1829 and 1830 under the Syndics Act to promote primary education in Lower Canada.

But Girouard’s relations with important people in his parish were far from cordial when the question of the appointment of churchwardens had to be dealt with. According to his successor, from 1820 Girouard was under pressure to let the habits à poches (justices of the peace, notaries, doctors, merchants, and persons of independent means) attend the meeting held each year to decide who would replace the outgoing churchwarden. In December 1830 a lawsuit was even brought against him for having called a meeting of the churchwardens, both old and new, rather than one of prominent parishioners. The time had come for confrontation on the issue [see Louis Bourdages].

In 1823 Girouard had made a request to Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*] for the incorporation of the college, and to this end he had prepared a deed of conditional gift of his property to the future corporation. Bishop Plessis headed the list of members, whereas Bishop Lartigue’s name was conspicuous by its absence. But the following year, at the request of Plessis, despite his own reservations Girouard had to replace the name of the principal, Jean-Baptiste Bélanger, with that of Lartigue, the superior of the college, in the draft deed. Lartigue advised Édouard-Joseph Crevier, whom he appointed principal in 1825, to consult Girouard when necessary and to treat him with deference. With the next principal, Thomas Maguire*, Girouard’s relations were rather bad. Throughout this period the question of the incorporation of the college dragged on.

In response to a suggestion from Bishop Lartigue, Girouard drew up his will in 1830, bequeathing the equivalent of 11,000 livres in money and vestments to the parish church. He named Lartigue, “not in his capacity as a bishop but as a private individual,” sole legatee of all his personal and real estate. In May 1832 Girouard asked the bishop to relieve him of his parish charge, being “entirely confident that in appointing his successor the bishop will take into consideration the interests of his college, and even that on this point he will perhaps go so far as to deign to yield to the preferences of an old man who no longer has any thought but to desire what God desires. “Girouard and his bursar expressed themselves in favour of Crevier, who was then priest of the parish of Saint-Luc, on the Rivière Richelieu, and who, after teaching philosophy at the Séminaire de Nicolet, had been principal of the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe from 1825 till 1827, and then bursar of the institution and Girouard’s curate for a while.

On the way back from a trip to Saint-Luc, Girouard went to visit his friend François-Joseph Deguise, the parish priest at Varennes; it was there that on 3 Aug. 1832 he died. At that time plans for enlarging the college were already under discussion. In keeping with Girouard’s wish, Lartigue made over to the corporation of the college – legal status finally came in 1833 – all the assets from the founder’s estate. Now firmly established and well endowed, the college was on its way to a sound future. As for the parish, Crevier would have to stand up to its prominent residents, and in particular many problems would be brought up over the rebuilding of the church. In Girouard’s obituary in La Minerve of 9 Aug. 1832 Joseph-Sabin Raymond*, who had been a pupil at the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe, rightly noted that death had just deprived “religion of a worthy minister, the country of a generous citizen, and education of a zealous advocate.” On the day of the funeral “stores were closed, work sites shut down” in Saint-Hyacinthe.

Antoine Girouard in a way was representative of the rural priests of the period 1800–30, an age when the initiatives of the Catholic clergy in Lower Canada met with less outright opposition than in the subsequent period. But beyond this, the founding of the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe was one of the bases for the development of the religious and educational institutions in that area. This development would contribute to the growth of the town, and, leaving its mark on Saint-Hyacinthe’s specific character, would account for its important intellectual role in the 19th century. Girouard was remembered personally as a robust, active, determined, and unaffected man.

ANQ-M, CE1-22, 7 oct. 1762. ASSH, Sect.A, sér.A. J.-S. Raymond, Discours prononcé à la translation du corps de messire Girouard, au séminaire de St-Hyacinthe, le 17 juillet 1861 (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., 1861). La Minerve, 9 août 1832. Allaire, Dictionnaire, vol. 1. Richard Chabot, Le curé de campagne et la contestation locale au Québec (de 1791 aux troubles de 1837–38): la querelle des écoles, l’affaire des fabriques et le problème des insurrections de 1837–38 (Montréal, 1975). C.-P. Choquette, Histoire du séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe depuis sa fondation jusqu’à nos jours (2v., Montréal, 1911–12). Jean Francœur, “Saint-Hyacinthe, esquisse de géographie urbaine” (thèse de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1954). P.-A. Saint-Pierre, Messire Antoine Girouard (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1938). É.-P. Chouinard, “L’abbé Joseph-Mathurin Bourg,” BRH, 6 (1900): 8–20. Lionel Groulx, “Les fondateurs de nos collèges,” Rev. nationale (Montréal), 11 (1929), no.12: 5–8; 12 (1930), no.1: 7–11.

Cite This Article

Jean-Paul Bernard, “GIROUARD, ANTOINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_antoine_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_antoine_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Paul Bernard |

| Title of Article: | GIROUARD, ANTOINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |

![Antoine Girouard [image fixe] Original title: Antoine Girouard [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.7491.jpg)