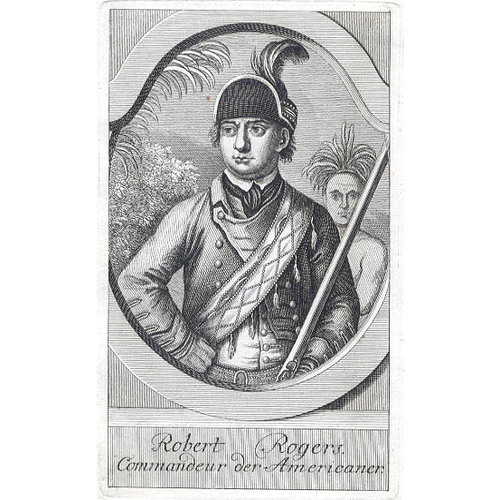

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ROGERS, ROBERT (early in his career he may have signed Rodgers), army officer and author; b. 8 Nov. 1731 (n.s.) at Methuen, Massachusetts, son of James and Mary Rogers; m. 30 June 1761 Elizabeth Browne at Portsmouth, New Hampshire; d. 18 May 1795 in London, England.

While Robert Rogers was quite young his family moved to the Great Meadow district of New Hampshire, near present Concord, and he grew up on a frontier of settlement where there was constant contact with Indians and which was exposed to raids in time of war. He got his education in village schools; somewhere he learned to write English which was direct and effective, if ill spelled. When still a boy he saw service, but no action, in the New Hampshire militia during the War of the Austrian Succession. He says in his Journals that from 1743 to 1755 his pursuits (which he does not specify) made him acquainted with both the British and the French colonies. It is interesting that he could speak French. In 1754 he became involved with a gang of counterfeiters; he was indicted but the case never came to trial.

In 1755 his military career proper began. He recruited men for the New England force being raised to serve under John Winslow, but when a New Hampshire regiment was authorized he took them into it, and was appointed captain and given command of a company. The regiment was sent to the upper Hudson and came under Major-General William Johnson. Rogers was recommended to Johnson as a good man for scouting duty, and he carried out a series of reconnaissances with small parties against the French in the area of forts Saint-Frédéric (near Crown Point, N.Y.) and Carillon (Ticonderoga). When his regiment was disbanded in the autumn he remained on duty, and through the bitter winter of 1755–56 he continued to lead scouting operations. In March 1756 William Shirley, acting commander-in-chief, instructed him to raise a company of rangers for scouting and intelligence duties in the Lake Champlain region. Rogers did not invent this type of unit (a ranger company under John Gorham* was serving in Nova Scotia as early as 1744) but he became particularly identified with the rangers of the army. Three other ranger companies were formed in 1756, one of them commanded by Rogers’ brother Richard (who died the following year).

Robert Rogers won an increasing reputation for daring leadership, though it can be argued that his expeditions sometimes produced misleading information. In January 1757 he set out through the snow to reconnoitre the French forts on Lake Champlain with some 80 men. There was fierce fighting in which both sides lost heavily, Rogers himself being wounded. He was now given authority over all the ranger companies, and in this year he wrote for the army what may be called a manual of forest fighting, which is to be found in his published Journals. In March 1758 another expedition towards Fort Saint-Frédéric, ordered by Colonel William Haviland against Rogers’ advice, resulted in a serious reverse to the rangers. Rogers’ reputation with the British command remained high, however, and as of 6 April 1758 Major-General James Abercromby, now commander-in-chief, gave him a formal commission both as captain of a ranger company and as “Major of the Rangers in his Majesty’s Service.” That summer Rogers with four ranger companies and two companies of Indians took part in the campaign on Lac Saint-Sacrement (Lake George) and Lake Champlain which ended with Abercromby’s disastrous defeat before Fort Carillon. A month later, on 8 August, Rogers with a mixed force some 700 strong fought a fierce little battle near Fort Ann, New York, with a smaller party of Frenchmen and Indians under Joseph Marin de La Malgue and forced it to withdraw.

British doubts of the rangers’ efficiency, and their frequent indiscipline, led in this year to the formation of the 80th Foot (Gage’s Light Infantry), a regular unit intended for bush-fighting. The rangers were nevertheless still considered essential at least for the moment, and Major-General Jeffery Amherst, who became commander-in-chief late in 1758, was as convinced as his predecessors of Rogers’ excellence as a leader of irregulars. Six ranger companies went to Quebec with James Wolfe* in 1759, and six more under Rogers himself formed part of Amherst’s own army advancing by the Lake Champlain route. In September Amherst ordered Rogers to undertake an expedition deep into Canada, to destroy the Abenaki village of Saint-François-de-Sales (Odanak). Even though the inhabitants had been warned of his approach, Rogers surprised and burned the village; he claims to have killed “at least two hundred” Indians, but French accounts make the number much smaller. His force retreated by the Connecticut River, closely pursued and suffering from hunger. Rogers himself with great energy and resolution rafted his way down to the first British settlement to send provisions back to his starving followers. The expedition cost the lives of about 50 of his officers and men. In 1760 Rogers with 600 rangers formed the advance guard of Haviland’s force invading Canada by the Lake Champlain line, and he was present at the capitulation of Montreal.

Immediately after the French surrender, Amherst ordered Rogers to move with two companies of rangers to take over the French posts in the west. He left Montreal on 13 September with his force in whaleboats. Travelling by way of the ruined posts at the sites of Kingston and Toronto (the latter “a proper place for a factory” he reported to Amherst), and visiting Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh, Pa) to obtain the instructions of Brigadier Robert Monckton, who was in command in the west, he reached Detroit, the only fort with a large French garrison, at the end of November. After taking it over from François-Marie Picoté de Belestre he attempted to reach Michilimackinac (Mackinaw City, Mich.) and Fort Saint-Joseph (Niles), where there were small French parties, but was prevented by ice on Lake Huron. He states in his later A concise account of North America (but not in his report written at the time) that during the march west he met Pontiac*, who received him in a friendly manner and “attended” him to Detroit.

With the end of hostilities in North America the ranger companies were disbanded. Rogers was appointed captain of one of the independent companies of regulars that had long been stationed in South Carolina. Subsequently he exchanged this appointment for a similar one in an independent company at New York; but the New York companies were disbanded in 1763 and Rogers went on half pay. When Pontiac’s uprising broke out he joined the force under Captain James Dalyell (Dalzell), Amherst’s aide-de-camp, which was sent to reinforce the beleaguered garrison of Detroit [see Henry Gladwin]. Rogers fought his last Indian fight, with courage and skill worthy of his reputation, in the sortie from Detroit on 31 July 1763.

By 1764 Rogers was in serious financial trouble. He had encountered at least temporary difficulty in obtaining reimbursement for the funds he had spent on his rangers, and the collapse of a trading venture with John Askin* at the time of Pontiac’s uprising worsened his situation. According to Thomas Gage he also lost money gambling. In 1764 he was arrested for debt in New York but soon escaped.

Rogers went to England in 1765 in hope of obtaining support for plans of western exploration and expansion. He petitioned for authority to mount a search for an inland northwest passage, an idea which may possibly have been implanted in his mind by Governor Arthur Dobbs of North Carolina. To enable him to pursue this project he asked for the appointment of commandant at Michilimackinac, and in October 1765 instructions were sent to Gage, now commanding in America, that he was to be given this post. He was also to be given a captain’s commission in the Royal Americans; this it appears he never got.

While in London Rogers published at least two books. One was his Journals, an account of his campaigns which reproduces a good many of his reports and the orders he received, and is a valuable contribution to the history of the Seven Years’ War in America. The other, A concise account of North America, is a sort of historical geography of the continent, brief and lively and profiting by Rogers’ remarkably wide firsthand knowledge. Both are lucid and forceful, rather extraordinary productions from an author with his education. He doubtless got much editorial help from his secretary, Nathaniel Potter, a graduate of the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) whom he had met shortly before leaving America for England; but Sir William Johnson’s description of Rogers in 1767 as “a very illiterate man” was probably malicious exaggeration at best. Both books were very well received by the London critics. A less friendly reception awaited Ponteach; or, the savages of America: a tragedy, a play in blank verse published a few months later. It was anonymous but seems to have been generally attributed to Rogers. John R. Cuneo has plausibly suggested that the opening scenes, depicting white traders and hunters preying on Indians, may well reflect the influence of Rogers, but that it is hard to connect him with the highflown artificial tragedy that follows. Doubtless, in Francis Parkman’s phrase, he “had a share” in composing the play. The Monthly Review: or, Literary Journal rudely called Ponteach “one of the most absurd productions of the kind that we have seen,” and said of the “reputed author”, “in turning bard, and writing a tragedy, he makes just as good a figure as would a Grubstreet rhymester at the head of our Author’s corps of North-American Rangers.” No attempt seems to have been made to produce the play on the stage.

His mission to London having had, on the whole, remarkable success, Rogers returned to North America at the beginning of 1766. He and his wife arrived at Michilimackinac in August, and he lost no time in sending off two exploring parties under Jonathan Carver and James Tute, the latter being specifically instructed to search for the northwest passage. Nothing important came of these efforts.

Both Johnson, who was now superintendent of northern Indians, and Gage evidently disliked and distrusted Rogers; Gage no doubt resented his having gone to the authorities in London over his head. On hearing of Rogers’ appointment Gage wrote to Johnson: “He is wild, vain, of little understanding, and of as little Principle; but withal has a share of Cunning, no Modesty or veracity and sticks at Nothing . . . He deserved Some Notice for his Bravery and readiness on Service and if they had put him on whole Pay. to give him an Income to live upon, they would have done well. But, this employment he is most unfit for, and withal speaks no Indian Language. He made a great deal of money during the War, which was squandered in Vanity and Gaming. and is some Thousands in Debt here [in New York].” Almost immediately Gage received an intercepted letter which could be read as indicating that Rogers might be intriguing with the French. Rogers was certainly ambitious and clearly desired to carve out for himself some sort of semi-independent fiefdom in the west. In 1767 he drafted a plan under which Michilimackinac and its dependencies should be erected into a “Civil Government,” with a governor, lieutenant governor, and a council of 12 members chosen from the principal merchants trading in the region. The governor and council would report in all civil and Indian matters direct to the king and the Privy Council in England. This plan was sent to London and Rogers petitioned the Board of Trade for appointment as governor. Such a project was bound to excite still further the hostility of Gage and Johnson, and it got nowhere. Rogers quarrelled with his secretary Potter and the latter reported that his former chief was considering going over to the French if his plan for a separate government was not approved. On the strength of an affidavit by Potter to this effect Gage ordered Rogers arrested and charged with high treason. This was done in December 1767 and in the spring Rogers was taken east in irons. In October 1768 he was tried by court martial at Montreal on charges of “designs . . . of Deserting to the French . . . and stirring up the Indians against His Majesty and His Government”; “holding a correspondence with His Majesty’s Enemies”; and disobedience of orders by spending money on “expensive schemes and projects” and among the Indians. Although these charges were supported by Benjamin Roberts, the former Indian department commissary at Michilimackinac, Rogers was acquitted. It seems likely that he had been guilty of no crime more serious than loose talk. The verdict was approved by the king the following year, though with the note that there had been “great reason to suspect . . . an improper and dangerous Correspondence.” Rogers was not reinstated at Michilimackinac. In the summer of 1769 he went to England seeking redress and payment of various sums which he claimed as due him. He received little satisfaction and spent several periods in debtors’ prison, the longest being in 1772–74. He sued Gage for false imprisonment and other injuries; the suit was later withdrawn and Rogers was granted a major’s half pay. He returned to America in 1775.

The American Revolutionary War was now raging. Rogers, no politician, might have fought on either side, but for him neutrality was unlikely. His British commission made him an object of suspicion to the rebels. He was arrested in Philadelphia but released on giving his parole not to serve against the colonies. In 1776 he sought a Continental commission, but General George Washington distrusted and imprisoned him. He escaped and offered his services to the British headquarters at New York. In August he was appointed to raise and command with the rank of lieutenant-colonel commandant a battalion which seems to have been known at this stage as the Queen’s American Rangers. On 21 October this raw unit was attacked by the Americans near Mamaroneck, New York. A ranger outpost was overrun but Rogers’ main force stood firm and the attackers withdrew. Early in 1777 an inspector general appointed to report on the loyalist units found Rogers’ in poor condition, and he was retired on half pay. The Queen’s Rangers, as they came to be known, later achieved distinction under regular commanders, notably John Graves Simcoe*.

Rogers’ military career was not quite over. Returning in 1779 from a visit to England, he was commissioned by General Sir Henry Clinton – who may have been encouraged from London – to raise a unit of two battalions, to be recruited in the American colonies but organized in Canada, and known as the King’s Rangers. The regiment was never completed and never fought. The burden of recruiting it fell largely on Rogers’ brother James, also a ranger officer of the Seven Years’ War. Robert by now was drunken and inefficient, and not above lying about the number of men raised. Governor Frederick Haldimand wrote of him, “he at once disgraces the Service, & renders himself incapable of being Depended upon.” He was in Quebec in 1779–80. At the end of 1780, while on his way to New York by sea, he was captured by an American privateer and spent a long period in prison. By 1782 he was back behind the British lines. At the end of the war he went to England, perhaps leaving New York with the British force at the final evacuation in 1783.

Rogers’ last years were spent in England in debt, poverty, and drunkenness. Part of the time he was again in debtors’ prison. He lived on his half pay, which was often partly assigned to creditors. He died in London “at his apartments in the Borough [Southwark],” evidently intestate; letters of administration of his estate, estimated at only £100, were granted to John Walker, said to be his landlord. His wife had divorced him by act of the New Hampshire legislature in 1778, asserting that when she last saw him a couple of years before “he was in a situation which, as her peace and safety forced her then to shun & fly from him so Decency now forbids her to say more upon so indelicate a subject.” Their only child, a son named Arthur, stayed with his mother.

The extraordinary career that thus ended in sordid obscurity had reached its climax in the Seven Years’ War, before Rogers was 30. American legend has somewhat exaggerated his exploits; for he often met reverses as well as successes in his combats with the French and their Indian allies in the Lake Champlain country. But he was a man of great energy and courage (and, it must be said, of considerable ruthlessness), who had something of a genius for irregular war. No other American frontiersman succeeded so well in coping with the formidable bush-fighters of New France. That the frontiersman was also the author of successful books suggests a highly unusual combination of qualities. His personality remains enigmatic. Much of the evidence against him comes from those who disliked him; but it is pretty clear that his moral character was far from being on the same level as his abilities. Had it been so, he would have been one of the most remarkable Americans of a remarkable generation.

[Robert Rogers’ published works have all been reissued: Journals of Major Robert Rogers . . . (London, 1765) in an edition by F. B. Hough (Albany, N.Y., 1883) with an appendix of documents concerning Rogers’ later career, in a reprint with an introduction by H. H. Peckham (New York, [1961]), and in a facsimile reprint (Ann Arbor, Mich., [1966]); A concise account of North America . . . (London, 1765) in a reprint (East Ardsley, Eng., and New York, 1966); and the play attributed to Rogers, Ponteach; or, the savages of America: a tragedy (London, 1766), with an introduction and biography of Rogers by Allan Nevins (Chicago, 1914) and in Representative plays by American dramatists, ed. M. J. Moses (3v., New York, 1918-[25]), I, 115–208. Part of the play is printed in Francis Parkman, The conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian war after the conquest of Canada (2v., Boston, 1910), app.B.

Unpublished mss or transcripts of mss concerning Rogers are located in Clements Library, Thomas Gage papers, American series; Rogers papers; in PAC, MG 18, L4, 2, pkt.7; MG 23, K3; and in PRO, Prob. 6/171, f.160; TS 11/387, 11/1069/4957.

Printed material by or relating to Rogers can be found in The documentary history of the state of New-York . . . , ed. E. B. O’Callaghan (4v., Albany, 1849–51), IV; Gentleman’s Magazine, 1765, 584–85; Johnson papers (Sullivan et al.); “Journal of Robert Rogers the ranger on his expedition for receiving the capitulation of western French posts,” ed. V. H. Paltsits, New York Public Library, Bull., 37 (1933), 261–76; London Magazine, or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, XXXIV (1765), 630–32, 676–78; XXXV (1766), 22–24; Military affairs in North America, 1748–65 (Pargellis); Monthly Review: or, Literary Journal (London), XXXIV (1766), pt.1, 9–22, 79–80, 242; NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), VII, VIII, X; “Rogers’s Michillimackinac journal,” ed. W. L. Clements, American Antiquarian Soc., Proc. (Worcester, Mass.), new ser., 28 (1918), 224–73; Times (London), 22 May 1795; Treason? at Michilimackinac: the proceedings of a general court martial held at Montreal in October 1768 for the trial of Major Robert Rogers, ed. D. A. Armour (Mackinac Island, Mich., 1967).

The considerable Rogers cult that has been in evidence in the United States during the last generation probably owes a good deal to K. L. Roberts’ popular historical novel, Northwest passage (Garden City, N.Y., 1937; new ed., 2v., 1937). Entries for Rogers are to be found in the DAB and DNB. J. R. Cuneo, Robert Rogers of the rangers (New York, 1959) is an excellent biography based on a wide range of sources but marred by lack of specific documentation. See also: Luca Codignola, Guerra a guerriglia nell’America coloniale: Robert Rogers a la guerra dei sette anni, 1754–1760 (Venice, 1977), which contains a translation into Italian of Rogers’ Journals; H. M. Jackson, Rogers’ rangers, a history ([Ottawa], 1953); S. McC. Pargellis, Lord Loudoun, and “The four independent companies of New York,” Essays in colonial history presented to Charles McLean Andrews by his students (New Haven, Conn., and London, 1931; repr. Freeport, N.Y., 1966), 96–123; Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (2v., Boston, 1884; repr. New York, 1962); J. R. Cuneo, “The early days of the Queen’s Rangers, August 1776–February 1777,” Military Affairs (Washington), XXII (1958), 65–74; Walter Rogers, “Rogers, ranger and loyalist,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., VI (1900), sect.ii, 49–59. c.p.s.]

Cite This Article

C. P. Stacey, “ROGERS (Rodgers), ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_robert_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_robert_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. P. Stacey |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS (Rodgers), ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |