![Description Photograph of George Dixon Date Prior to 1909 Source Richard Kyle Fox (1909), The life and battles of Jack Johnson, New York: R.K. Fox, p. 32, OCLC 8613940, http://openlibrary.org/books/OL25127378M/The_life_and_battles_of_Jack_Johnson Author unattributed Other versions [1]

This is a retouched picture, which means that it has been digitally altered from its original version. Modifications: cropped, adjusted levels, removed minor artifacts, slight sepia. Modifications made by Scewing. The original can be found here. Azərbaycanca | Беларуская (тарашкевіца) | Català | Česky | Dansk | Deutsch | Zazaki | English | Esperanto | Español | Eesti | فارسی | Suomi | Français | Galego | Hrvatski | Magyar | Հայերեն | Italiano | 日本語 | ქართული | ភាសាខ្មែរ | 한국어 | Kurdî | Македонски | മലയാളം | Bahasa Melayu | Plattdüütsch | Nederlands | Polski | Português | Română | Русский | Slove Original title: Description Photograph of George Dixon Date Prior to 1909 Source Richard Kyle Fox (1909), The life and battles of Jack Johnson, New York: R.K. Fox, p. 32, OCLC 8613940, http://openlibrary.org/books/OL25127378M/The_life_and_battles_of_Jack_Johnson Author unattributed Other versions [1]

This is a retouched picture, which means that it has been digitally altered from its original version. Modifications: cropped, adjusted levels, removed minor artifacts, slight sepia. Modifications made by Scewing. The original can be found here. Azərbaycanca | Беларуская (тарашкевіца) | Català | Česky | Dansk | Deutsch | Zazaki | English | Esperanto | Español | Eesti | فارسی | Suomi | Français | Galego | Hrvatski | Magyar | Հայերեն | Italiano | 日本語 | ქართული | ភាសាខ្មែរ | 한국어 | Kurdî | Македонски | മലയാളം | Bahasa Melayu | Plattdüütsch | Nederlands | Polski | Português | Română | Русский | Slove](/bioimages/w600.2776.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

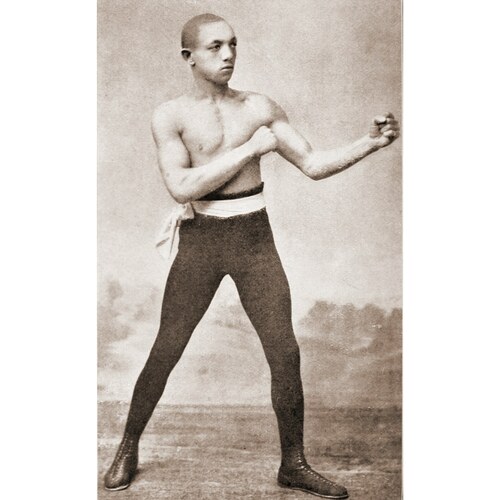

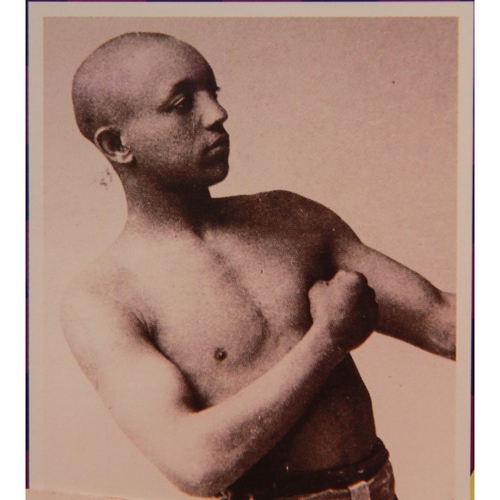

DIXON, GEORGE (Little Chocolate), boxer; b. 29 July 1870 in Halifax; m. Kitty O’Rourke, the sister of his manager; d. 6 Jan. 1908 in New York City.

George Dixon was born in the north end of Halifax. As a boy he was apprenticed to a photographer, and he became interested in boxing because local boxers came to his employer to sit for publicity photographs. His first fight, and his first knockout, took place in 1886. Shortly thereafter he moved to Boston to box. In 1887 he won twice, and the next year won five and drew six of eleven fights. During the latter half of the 19th century a fighter could compete in two weight classes at the same time, and Dixon took the opportunity to box in the bantamweight and the featherweight classes. He would today probably be considered a bantamweight.

At this period there appears to have been less consciousness of race among the lighter classes of boxers than among heavyweights [see George Godfrey], for Dixon was soon accepted as a worthy competitor. He came to notice after a series of battles with Hank Brennan, known as “the pride of Boston.” In February 1890 Dixon achieved wide recognition when after 70 rounds, the longest fight of his career, he drew with Cal McCarthy, bantam- and featherweight champion of the eastern United States. On 27 June Dixon and Nunc Wallace, the British bantam- and featherweight champion, fought in London, England. At the end of 18 rounds Wallace’s seconds acknowledged defeat.

The victory over Wallace gave Dixon a strong claim to the world bantamweight title, but he believed that before he could be recognized as champion he had to defeat three boxers with chances as good as his. In October 1890 he beat the first, Johnny Murphy, the Rhode Island featherweight champion, in a bout which lasted 40 rounds. In the 40th round, an account noted, Murphy’s body “looked as though it had been flayed.” Dixon had barely a scratch. Dixon met McCarthy again on 31 March 1891 for a purse of $4,000, and in the 22nd round McCarthy gave in, after having been knocked down several times. And then in San Francisco on 28 July Dixon knocked out Abe Willis, the Australian bantamweight champion, in five rounds, to become world bantamweight champion, the first black and the first Canadian to win a world boxing title.

The claim by Dixon that he was also world featherweight champion because he had beaten Wallace and McCarthy was not fully accepted. In order to silence his critics, on 27 June 1892 Dixon fought Fred Johnson, the new British featherweight champion, and won in 14 rounds. Six weeks later he opposed the amateur Jack Skelly in New Orleans in a bout which was advertised as being for the featherweight championship of the world, and he won easily in eight rounds to collect a purse of $17,500 and his second title.

Only 5 feet 3 1/2 inches tall and seldom weighing more than 120 pounds, Dixon was a formidable boxer because of his speed, agility, and power; his left-hand punches were considered especially dangerous. Moreover, he is credited with introducing innovations to fight training. Just before Dixon’s bout with Willis a reporter wrote that Dixon was believed by many to be “the best, self-trained man that ever stepped into the ring” and described his new training routine, in which “he uses a small pair of dumbbells, and with either hand he faces an imaginary opponent. As he feints and ducks before the ‘spook’ enemy, he advances on one and then the other foot.” The technique is today called shadow-boxing. Dixon is also thought to have been the first boxer to use the modern punching-bag, which is suspended from the ceiling.

The statistics of Dixon’s career still command attention. He often had between six and ten contests a year, and although many were short, four or five rounds, between 1896 and 1899 he was in 12 bouts of 20 and six of 25 rounds, and in 1903 he had three of 20 and three of 15. On several occasions Dixon travelled across the United States accepting challenges from all comers; in a week of one of these exhibitions he had 22 fights, a number very few modern boxers could match. Mainly because the number of exhibition fights cannot be determined, it is not known how many times Dixon boxed as a professional. His manager claimed that he was in at least eight hundred contests, and it has been suggested that there may have been as many as one thousand. These figures give Dixon one of the most impressive boxing records to date.

Dixon retired as a bantamweight in 1892 without being beaten as champion, but he lost his featherweight crown on 4 Oct. 1897 to Solly Smith in 20 rounds. Smith having lost the title himself the next year to Dave Sullivan, Dixon fought Sullivan on 11 Nov. 1898 and won when Sullivan was disqualified after his seconds entered the ring illegally. Dixon gave up the championship for good on 9 Jan. 1900 in New York City to Terry McGovern. Although he maintained a strong following, from then on he increasingly drew or lost against opponents he would easily have defeated in his younger days. He retired in 1906 after losing a 15-round contest.

Dixon estimated that boxing had earned him $250,000, but like many who suddenly acquire wealth he was unable to keep it. He liked to wear good clothes, entertain lavishly, and gamble, and he also gave generously to charities. By the end of his career he was practically penniless and had been reduced to fighting for small sums in order to make ends meet. During the last two years of his life he drank heavily. “A wasted and worn figure,” according to an obituary, he died two days after being admitted to New York’s Bellevue Hospital. His body was on view in an athletic club for two days before being sent to Boston for burial. Dixon was elected to the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame in 1955, and the next year he was nominated to the American Ring Hall of Fame. In 1968 a north-end Halifax recreation centre was named after this outstanding Canadian boxer, perhaps the best the country has produced.

The assistance of Wilfred McCluskey of Charlottetown and Barry Cahill of the PANS in the preparation of this biography is gratefully acknowledged.

Photographs of George Dixon appear in Canada’s sporting heroes and Sweat and soul (cited below). A play about his life, Shine boy, written by George Boyd, was presented in Halifax in 1988.

A lesson in boxing (n.p., 1893), a 15-page pamphlet “by George Dixon, champion featherweight of the world,” is preserved in the Library of Congress, Washington, and listed in the National union catalog.

PANS, MG 1, 783, file 4; MG 9, 43: 352. Acadian Recorder, 27 Oct. 1890; 1 April, 29 July 1891; 28 June, 7 Sept. 1892; 12 Nov. 1898; 10 Jan. 1900. Daily Patriot (Charlottetown), 7 Jan. 1908. Halifax Herald, 7 Jan. 1908. N. S. Fleischer, Black dynamite, the story of the negro in the prize ring from 1782 to 1928 (5v., New York, 1938–47), 3: 1–127. J. N. Grant, Black Nova Scotians (Halifax, 1980), 39. C. R. Saunders, Sweat and soul (Hantsport and Dartmouth, N.S., 1990), 20–27, 35, 45. S. F. Wise and Douglas Fisher, Canada’s sporting heroes (Don Mills [Toronto], 1974), 144–45.

Cite This Article

In collaboration, “DIXON, GEORGE (Little Chocolate) (1870-1908),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 13, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dixon_george_1870_1908_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dixon_george_1870_1908_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration |

| Title of Article: | DIXON, GEORGE (Little Chocolate) (1870-1908) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | November 13, 2024 |