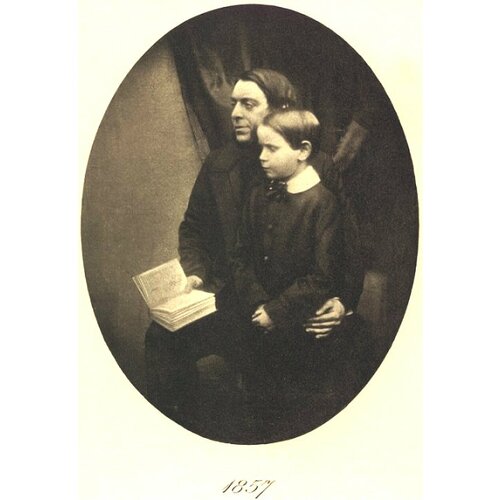

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

GOSSE, PHILIP HENRY, naturalist and religious writer; b. 6 April 1810 in Worcester, England, second of four children of Thomas Gosse, miniature portrait painter, and Hannah Best, domestic servant; m. first in 1848 Emily Bowes (d. 1857), and they had one son; m. secondly in 1860 Eliza Brightwen; d. 23 Aug. 1888 at St Mary Church, near Torquay, England.

Philip Henry Gosse was educated at local schools in Poole, Dorset; he especially valued the classical training he received from 1823 to 1824 at a nearby boarding-school in Blandford. “From infancy my tastes were bookish,” he recalled, and so when he left school at 15 his academic interests did not end. He developed a delight for the study of natural history long before his formal education ceased and throughout his life he was an adherent of the natural theology tradition. As well he was influenced by his father’s strong belief in evangelical Christianity, and inherited from him a keen interest in painting and drawing. After quitting school Gosse held a number of odd jobs until 1827 when a clerkship was obtained for him in the counting-house of Slade, Elson and Company in Carbonear, Nfld.

Arriving in Newfoundland in June 1827, Gosse found a colony divided into two warring classes, merchants and fishermen [see William Carson*]. This tension was exacerbated by the concomitant local and historical hostility between English Protestants and Irish Catholics, each vying for the upper hand in light of the prospect of representative government. Nevertheless, Gosse was able to pursue his chores at the counting-house, outfitting and tallying the catch of the seal fleets in March and April and the cod trade in June and October as well as copying letters and ledgers the rest of the year. This activity left plenty of spare time and Gosse participated in the local intellectual life, which included a book club and a debating society.

The year 1832 was Gosse’s annus mirabilis. Though his first few years in Newfoundland had been pleasant his life lacked direction. In May 1832 he purchased George Adams’ Essays on the microscope (London, 1787) which served to focus his hitherto diffuse though eager interest in natural history. Then in the next month a letter from home announcing that his sister Elizabeth was on the verge of death stirred his conscience and raised the issue of his relationship with God once again, resulting in an evangelical conversion. Thus Gosse commenced the two activities which dominated the remainder of his life, the study of nature and the practice of evangelical Christianity.

In November 1832 Gosse began systematically to collect insects and to enter scientific observations in journals. Extracts from his meteorological record were published in the Conception-Bay Mercury. In the following summer he commenced filling a volume (“Entomologia Terrae Novae”) with coloured drawings of butterflies, moths, beetles, and other insects; despite an unusually high level of scientific accuracy, it has remained unpublished. Meanwhile, he had joined the Methodist society in Carbonear, read the theological works of John and Charles Wesley, become a member of the chapel choir, participated in public prayer-meetings, and was eventually persuaded to act as a local preacher with Philip Tocque* and others.

In June 1835 Gosse left Newfoundland. He had fulfilled the terms of his indenture at the countinghouse, and the mounting tension between the Irish Catholics and English Protestants following the granting of representative government in 1832 was making life unbearable for him. Moreover, he had “pretty well exhausted Entomology in Newfoundland; it was a cold barren unproductive region.” One of Gosse’s close friends, George Edward Jaques, and his wife had heard some “very flaming accounts” about Canada and were intent on moving there. Gosse decided to join them and together they purchased 110 partially cleared acres just north of Compton, Sherbrooke County Lower Canada.

For the next three years Gosse worked his 60 acres of the land in the face of constant hardship. Although Compton was situated in an area reputed to be rich agriculturally, the short seasons often forced settlers to work at trades more profitable than farming; in the winter months Gosse taught school to supplement his; income. Jaques and Gosse farmed separately and without the help of agricultural labourers who were in short supply; through inexperience, they grew crop which were sold only with difficulty. In spite of an initial wave of optimism it soon became apparent that the experiment was a failure, and Gosse left the colony in March 1838, spending seven months in Alabama before returning to England early in 1839. Except for an 18-month sojourn in Jamaica he remained in England for the rest of his life.

During his years in Canada Gosse’s spiritual life was at a low ebb, with nourishment coming only from the irregularly held Methodist services in Compton and the winter prayer-meetings. On the other hand, his scientific pursuits gradually became “from the mere salt, the condiment, of life, almost its very pabulum.” He was often seen in the field collecting insects, and people spoke of him as “that crazy Englishman who goes about collecting bugs.” During his first winter in Canada he had assembled his scientific journals and composed “The entomology of Newfoundland,” apparently the companion to the volume of illustrations. Although excerpts from these journals were subsequently published, Gosse realized that the book itself was unworthy of publication and it remained in manuscript. Modest recognition was given to his scientific pursuits in 1836 when he was elected a corresponding member of two societies to which he sent papers, the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec and the Natural History Society of Montreal. In May 1837, after five years of accumulating data, Gosse decided to bring his observations together into a general work on Canadian natural history. Three years later, The Canadian naturalist: a series of conversations on the natural history of Lower Canada was published in London, with his own illustrations.

In the years that followed Gosse wrote more than 40 books and pamphlets as well as 230 articles on religious and scientific themes. As a naturalist he is best known for his original, often pioneering, works on invertebrate marine zoology, ornithology, rotifera, and lepidoptera. He was the foremost popularizer of natural history in mid-Victorian England, and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1856. His religious works, in which he was deeply influenced by the Plymouth Brethren, include prophetic, hortative, and exegetical essays, as well as attempts to resolve the conflict between religion and science.

Gosse made no impact on the religious life of either Newfoundland or Canada. In the history of entomology in Newfoundland, however, he occupies a special place, for in a day when the colony did not possess any men of science, scientific institutions, or even cabinet collections, he was the first person systematically to investigate and to record the entomology of that island. No such status can be assigned to his Canadian investigations, especially since he himself recognized his deficiency in the systematic knowledge of natural history. The Canadian naturalist, presented as a conversation between a father and son, was old-fashioned in format and addressed to a popular rather than to a learned audience. Yet Gosse brought together much accurate and original information about the flora and fauna of the Eastern Townships, focusing his attention on ecology rather than taxonomy, and the book and its illustrations were well received. “[From] this book,” Charles James Stewart Bethune* wrote in 1898, “many Canadian entomologists of note received their first lessons, and learned the names of some of our common butterflies and moths.”

Gosse was the author of The Canadian naturalist: a series of conversations on the natural history of Lower Canada (London, 1840; repr. Toronto, 1971); “List of butterflies taken at Compton, in Lower Canada,” Entomologist (London), 1 (1840–42): 137–39; “Notes on butterflies obtained at Carbonear Island, Newfoundland, 1832–1835,” Canadian Entomologist (London, Ont.), 15 (1883): 44–51; “On silk produced by diurnal Lepidoptera,” Intellectual Observer (London), 10 (1866–67): 393–94; “The Y-shaped organ of Papilio larvæ,” Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip (London), 8 (1871): 224. For other works by Gosse and a study of his life see D. L. Wertheimer, “Philip Henry Gosse: science and revelation in the crucible” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1977).

National Museums of Canada Library (Ottawa), P. H. Gosse, “Entomologia Terrae Novae,” c.1835. PAC, MG 24, 163. PANL, T. B. Browning papers, Sketchbook of Newfoundland scenes, apparently by William Gosse. S. H. Scudder, “Gosse’s observations on the butterflies of North America,” Psyche (Cambridge, Mass.), 3 (1881): 245–47. R. B. Freeman and Douglas Wertheimer, Philip Henry Gosse: a bibliography (Folkestone, Eng., 1980). E. W. Gosse, Father and son; a study of two temperaments (London, 1907); The life of Philip Henry Gosse, F.R.S. (London, 1890). C. J. S. Bethune, “The rise and progress of entomology in Canada,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., 4 (1898), sect.iv: 155–65. F. A. Bruton, “Philip Henry Gosse’s entomology of Newfoundland; introductory note,” Entomological News (Philadelphia), 41 (1930): 34–38. T. W. Fyles, “A visit to the Canadian haunts of the late Philip Henry Gosse,” Entomological Soc. of Ont., Annual report (Toronto), 23 (1892): 22–29.

Cite This Article

Douglas Wertheimer, “GOSSE, PHILIP HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gosse_philip_henry_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gosse_philip_henry_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Douglas Wertheimer |

| Title of Article: | GOSSE, PHILIP HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |