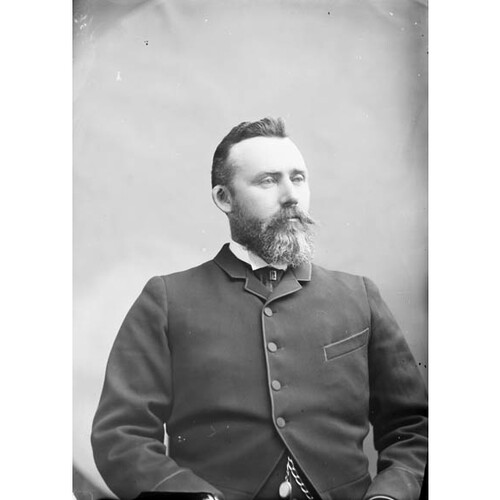

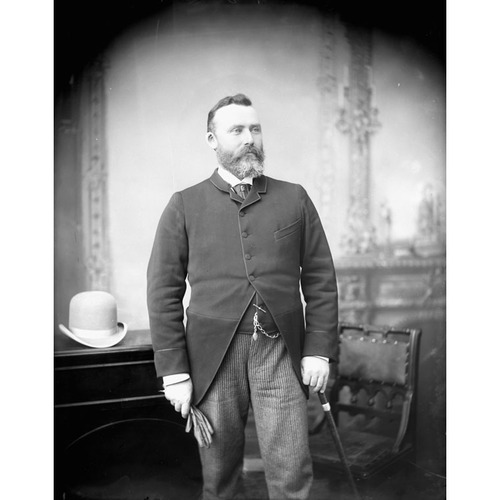

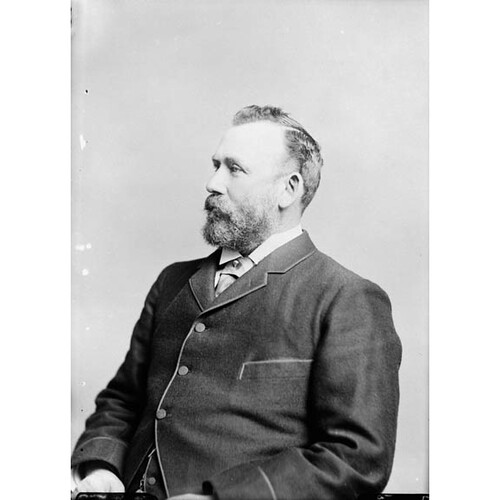

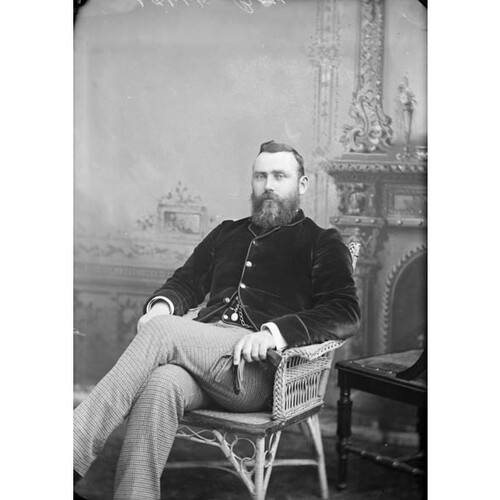

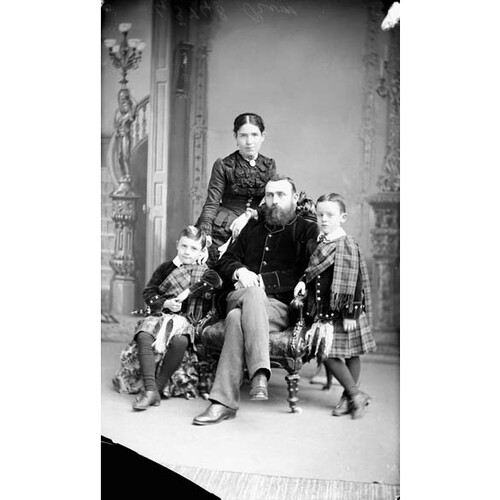

ROSS, ARTHUR WELLINGTON, teacher, office holder, lawyer, businessman, and politician; b. 25 March 1846 in Nairn, Upper Canada, eldest son of Donald Ross and Margaret —; m. 30 July 1873 Jessie Flora Cattanach, daughter of Donald Cattanach of Laggan, Ont., and they had two sons; d. 25 March 1901 in Toronto.

Arthur Wellington Ross claimed later in life that he had known firsthand the hardships suffered by those Scottish crofters who left “the smoldering ruins of the cottages in which their forefathers were born” to seek a new home in Upper Canada, only to end up “digging their grave by so doing.” His Scottish Presbyterian father, who worked a marginal farm in East Williams Township, conveyed few advantages to his son beyond a sound education. After attending the local common school, Ross left the farm for Wardsville Grammar School. A teaching career attracted him as a way out of a rural life that had brought little material success to his family. Therefore he enrolled in the Toronto Normal School, and he qualified for a first-class certificate probably about 1865 or 1866. He taught in Cornwall and so impressed trustees there that in 1868 they hired him as headmaster of the high school. In September 1871 he was made inspector of public schools for Glengarry County, a position newly created by the School Act of that year.

Rapid as his advancement was, Ross considered teaching only a stepping-stone to a more lucrative and respected profession. He continued his studies and in 1874 received a ba from the University of Toronto. He then resigned his inspectorship to be articled to an attorney and solicitor. His impatience for advancement manifested itself when he moved to Winnipeg with his younger brother William Henry Ross in early June 1877, just five months before completing his law studies. He was articled to his brother, who was already a lawyer, but because his training had been interrupted by the move, he had to obtain a special act from the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba to be admitted to the bar, in 1878. The Ross brothers practised in partnership, acting briefly as solicitors in Winnipeg for the government of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie*. Albert Clements Killam joined the practice in 1879 and, following William Henry’s death that year, Alexander Haggart was admitted as a junior partner in the firm, which became Ross, Killam, and Haggart.

Real estate speculation quickly became Ross’s major business interest. By 1882 he was among the wealthiest one per cent of landowners residing in Winnipeg: his real estate assessment that year totalled approximately $210,000 and was the eighth highest individual assessment in the city. In addition to his city property, he owned nearly the whole of the suburban area later known as Fort Rouge (Winnipeg), where he built one of the most impressive residences of the boom era. As well, he speculated in Métis scrip, lands owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company, town lots in Brandon and Edmonton, and various rural properties. In one transaction alone in 1880 he sold 25,000 acres. The Department of the Interior later believed, but could not prove conclusively, that Ross and his firm had benefited from information supplied by an employee in the office of its dominion lands branch in Winnipeg. Alexander Mackinnon Burgess*, deputy minister of the interior, reported in 1885 to his minister, Thomas White*, that “having the inside track in this way, they were able, on every occasion of receipt of a list of Half Breed allotments to be on the spot at the right time, to their own great advantage, and the disadvantage of all other speculators in the same class of claims.”

The collapse of western land values in 1882 ruined Ross. His practice, like that of other speculators, had been to purchase land with a minimum down payment and sell his holdings quickly before subsequent instalments fell due. His buyers, smaller-scale speculators themselves, engaged in a similar strategy, so that Ross had to depend on remittances from them to meet his own commitments or find buyers for the promissory notes which he accepted as security for his sales. When values dropped, he was trapped between his creditors, most notably the HBC, which relentlessly demanded payment, and his own customers, many of whom were prepared to walk away from their investments and obligations. In 1884 the HBC initiated a case in the Court of Chancery to recover properties sold on credit to Ross. The fate of the insolvent Ross became a topic of debate in the local press. The Commercial denounced him as a swindler who had engaged “in the wildest schemes of speculation with funds altogether inadequate for a tithe of his undertakings.” More sympathetic was the Daily Times, which judged Ross no more guilty than the other hapless speculators caught by an adverse turn of events. His creditors should accept a compromise. “It is unjust . . . to strike a man when he is down,” it noted. “It is not in keeping with the free air of the Northwest. It savours of the east, where usurious Shylocks are heady to grind the last dollar out of a man.”

Ross was not one to accept failure easily and he would concentrate on politics as an avenue for recovery. In the provincial general election of December 1878, he had narrowly won in the riding of Springfield as a Liberal and opponent to the government of John Norquay*. He was re-elected in the general election of 1879. In the assembly, railways in particular attracted his attention. Although he doubted whether Norquay’s policy of limited subsidies would significantly aid rail construction, he became associated with the promotion of the Manitoba and North Western Railway at some point during its history and served as its vice-president. When terms of the contract for the Pacific railway were announced by the federal government in 1880, he introduced a motion in the Manitoba assembly calling on the dominion government to cancel the agreement. Ross objected to the monopoly granted to the syndicate headed by George Stephen* and asserted that “the people of Canada were willing to pay taxes to build the road, but they did not want it run for the benefit of capitalists.” His vocal opposition, not to mention his Liberal credentials, made him attractive as a representative of western interests in the syndicate Sir William Pearce Howland assembled to tender a counter-offer for the transcontinental railway contract in January 1881. Although the bid of the Howland syndicate declared that Ross, the only westerner in the group, intended to take shares in the company should it be awarded the contract, it did not name him as a future director, nor did he deposit security for the tender.

Ross’s criticism of the Canadian Pacific Railway stood him in good stead when in 1882 he resigned from the provincial legislature to contest the riding of Lisgar for the Liberals in the federal election. Initially, he was reluctant to run since the constituency had been gerrymandered to secure it for the Conservative incumbent, John Christian Schultz*. Local opinion had been grossly offended, however, by Schultz’s failure to support the town of Selkirk as the location for the bridging of the Red River by the CPR. So determined were the Liberal organizers in Lisgar to unseat Schultz, Ross’s campaign manager later explained, that when the polls closed they “had a couple of Deputy Returning Officers with their Ballot Boxes corralled at Selkirk ready for any emergency, but thank goodness it was not necessary, [Ross] was elected fair.” In Ottawa Ross looked after the interests of his constituents as best he could, lobbying for facilities for Selkirk and enquiring about land titles as well as timber and mining locations for speculators.

But as his own affairs deteriorated, he needed to do more than provide good representation for his constituency. An opportunity presented itself in February 1884 when the CPR sought additional financial assistance from the dominion government. In a surprising turnaround Ross spoke eloquently in defence of the company, and even its monopoly, as crucial to the prosperity of the northwest and Canada, and to the growth of national sentiment in general. Ross repeated his role as a defender of the CPR the next year when the company sought parliamentary approval for another loan. Whether Ross had discussed with its officials the services he might render before making his speech in the House of Commons is not clear. But by the late summer of 1884 he was in Vancouver acting on the CPR’s behalf to assemble land for its western terminus at Granville (Vancouver). Ross also was ideally placed to speculate himself and he purchased town-site lots from the CPR. In 1886 he opened a real estate business, which was run for a short time by his brother-in-law, Malcolm Alexander MacLean*. Two years later Ross, who had divided his time between the west coast, Winnipeg, and Ottawa, moved to Vancouver, where he went into the real estate and insurance business with Henry Tracy Ceperley. The partnership lasted only two or three years, and Ross was back in the real estate business at Winnipeg in 1891.

Ross feared that his association with the CPR might jeopardize his political career, and he entered the campaign of 1887, now a Conservative, with trepidation. Consequently he pressed CPR vice-president William Cornelius Van Horne* to help get out the vote on his behalf. Van Horne instructed William Whyte*, general superintendent of the western division of the railway, to schedule special trains to carry voters to the polls and to make out spurious bills indicating that Ross had paid for the train service. Should any of the railway’s managers question these exceptional measures, Whyte was to explain that Ross had to be rewarded for helping the company “at a time [when] it was a question of the salvation or destruction of the whole enterprise.” Finally, Van Horne ordered that any man who revealed details of the arrangement “should be bounced without much ceremony.” Ross did not need to draw upon the railway’s assistance; he was re-elected by acclamation.

The eloquence of his defence of the CPR contrasted with the relative silence which attended his remaining ten years in the House of Commons. Although he spoke occasionally and briefly on issues relating to dominion lands and land grants to railways, he said nothing on such major issues as the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway]. Perhaps he could see little personal gain from debate. In fairness, he had received no encouragement from the Conservative party to speak out. Possibly anticipating the decease of Schultz with an unseemly eagerness, in 1891 he pressed John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*, a senator and lawyer for the CPR, for appointment as lieutenant governor of Manitoba. He was, he reminded Abbott, the senior western mp and he had spent more money to win his seat in the last election than all other Conservative candidates in Manitoba. “So far I have never got anything from the party and I think it is time I should be recognized.” He was not.

Little wonder Ross did not contest the election of 1896. Instead he devoted himself to new speculations. He left Winnipeg in 1896 for Toronto, where he became a broker of mining securities and general manager of the North Star Mining, Trading, and Transportation Company. His interests in the goldfields of Rossland, B.C., led him to move to nearby Columbia Gardens about 1899. It was there in January 1901 that he suffered a paralysing stroke. He returned to Toronto for medical treatment, but died of a second stroke.

In reviewing the party affiliations of the members of parliament from Manitoba in 1882, Joseph Royal, himself one of the group, maintained that “Ross was elected for Ross.” He was probably correct. Arthur Wellington Ross was one of those ambitious young men from Ontario who headed west in the 1870s to seek their fortunes. With that single purpose in mind and little concern for public opprobrium, he sought to seize opportunities, whether in business speculations or in politics.

City of Winnipeg Arch., Assessment rolls, 1882. NA, MG 26, C: 690–92; MG 28, III 20, Van Horne letter-books, 3: 571–73; 7: 628–32; 9: 208–9, 321–22, 601; 11: 414; 13: 539–40; 15: 698; 16: 538; 19: 548; 20: 280–81, 285; MG 29, E114, letter-book: 359; RG 31, C1, 1851, East Williams, dist.2: 31, 63; 1861, East Williams: 1; agricultural census: 102. PAM, MG 14, B57, letter-book 3: 111–18, 204–6, 214, 224–25; letter-book 4: 119–20, 130, 150–51, 232–33, 294–95, 302. Commercial (Winnipeg), 30 June, 14 July 1885. Daily Times (Winnipeg), 24 Dec. 1880, 9 July 1885. Manitoba Morning Free Press, 22 Jan., 12, 19, 28 Dec. 1878; 5 Feb. 1879; 25 March 1901. Winnipeg Tribune, 28 March 1901.

C. J. Brydges, The letters of Charles John Brydges, 1879–1882, Hudson’s Bay Company land commissioner, ed. Hartwell Bowsfield, intro. Alan Wilson (Winnipeg, 1977); The letters of Charles John Brydges, 1883–1889, Hudson’s Bay Company land commissioner, ed. Hartwell Bowsfield, intro. J. E. Rea (Winnipeg, 1981). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1883–85, 1887, 1890; Parl., Sessional papers, 1880–81, nos.23m–n. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Directory, Man., 1888–89, 1891, 1895–96. Man., Statutes, 1878, c.38.

Cite This Article

David G. Burley, “ROSS, ARTHUR WELLINGTON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_arthur_wellington_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_arthur_wellington_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | ROSS, ARTHUR WELLINGTON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |