Source: Link

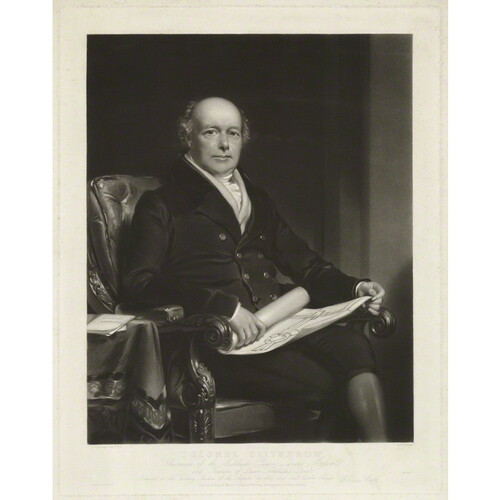

CLITHEROW, JOHN, army officer, politician, and colonial administrator; b. 13 Dec. 1782 in Essendon, England, eldest son of Christopher Clitherow and Anne Jodrell; d. 14 Oct. 1852 at Boston House, Brentford, England.

Descended from Sir Christopher Clitherow, lord mayor of London in 1635, John Clitherow entered the British army on 19 Dec. 1799 as ensign in the 3rd Foot Guards, which in 1831 became the Scots Fusilier Guards. He served in the Egyptian campaign of 1801 and on the expeditions to Hanover (Federal Republic of Germany) in 1805 and to Walcheren, Netherlands, in 1809, and was wounded twice in the Peninsular War. He attained the rank of colonel on 25 July 1821, major-general on 22 July 1830, and lieutenant-general on 23 Nov. 1841.

Clitherow arrived in British North America in March 1838 as commanding officer for the military district of Montreal. Four months later he was asked by Lord Durham [Lambton*] to serve on the Special Council after Durham had dismissed the members appointed by Sir John Colborne* and chosen men from his own civil and military entourage. Durham expressed the need for councillors free of local party ties and formed the new council largely for the purpose of sanctioning measures proposed by him to deal with the aftermath of the rebellion of 1837. Clitherow, like the four other military men on the eight-member council (including Major-General James Macdonell), felt some uneasiness at being involved, even nominally, in the civil legislative process. Durham insisted, however, that were Clitherow or the other military men to withdraw, he would be unable to carry on and, under those circumstances, Clitherow sat on the council from 9 July until 2 Nov. 1838, the day after Durham’s departure for England.

In early September 1838 Clitherow became alarmed at the frequency and nature of intelligence reports from the area near the United States border concerning intended disturbances. To ascertain the accuracy of the reports himself, he visited Île aux Noix and returned to Montreal convinced that they were greatly exaggerated. It may have been his appraisal of the area south of the St Lawrence that led Colborne, commander-in-chief of the forces in the Canadas, to underestimate the danger of insurrection at that time.

When the second uprising broke out on 3 Nov. 1838, Clitherow commanded the left wing of the army of 3,000 regulars that marched on the rebel headquarters at Napierville. Clitherow’s brigade, consisting of the 15th and 24th Foot, converged on the village on the morning of 10 November at the same time as a second brigade commanded by Macdonell. However, the rebels had dispersed before the troops’ arrival and Clitherow’s brigade proceeded to Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu) by way of Henryville while the second brigade returned to Montreal by way of Clarenceville, a sweeping movement designed to impress upon the disaffected the futility of continued resistance.

Clitherow was more at ease in performing these purely military operations, yet when called upon to assume civil and judicial duties he did so without giving offence. As senior military officer of the Montreal district, he presided at the general courts martial assembled in November 1838 to try the 108 men charged with treason in connection with the insurrection. Although these courts martial were conducted in English, which few of the prisoners understood, Clitherow appears to have acted impartially and with goodwill towards the accused. These trials engendered contemporary criticism. Some loyalists condemned them as too lenient towards the insurgents, others such as Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Grey found fault with the way they were prosecuted. During the debate on the Rebellion Losses Bill in 1849, Attorney General Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* challenged their legality. More recent scholarship has reiterated this challenge. Yet in his work on the rebellions, Gérard Filteau considers that “the military judges accomplished their duty in a spirit of justice and even . . . benevolence.”

Clitherow remained in Montreal until July 1841 when he took command of the forces in Upper Canada, with headquarters at Kingston. In his capacity as senior military officer, he was made deputy governor by Lord Sydenham [Thomson*] on 18 Sept. 1841 and prorogued the first session of the first parliament of the Province of Canada the day before Sydenham died. Clitherow continued to act as deputy governor for six days until the appointment of Sir Richard Downes Jackson* as administrator.

Little is known of Clitherow’s immediate family. In January 1809 he married Sarah Burton, and John Christie Clitherow of the Coldstream Guards, who appears to have been the only child of this marriage, served as his father’s aide-de-camp when the latter was stationed in the Canadas. Clitherow remarried in 1825, taking as his wife Millicent Pole of Gloucestershire. He inherited the family estate at Boston House when his cousin James Clitherow died in October 1841 and he returned to England in June 1842. He was succeeded as commander of the forces in Upper Canada by Sir Richard Armstrong. In January 1844 he became colonel of the 67th Foot, an appointment he held until his death. He was made a knight of the Crescent in 1845.

Clitherow was, above all, a military man, concerned about the administration, efficiency, and image of his command, so much so that officers were glad to move their regiments south of the St Lawrence River to get away from his close scrutiny. His duties on Durham’s Special Council, as president of the general courts martial, and as deputy governor were largely nominal. In Montreal he and his wife went beyond the call of duty in cultivating social links. For instance, they attended a service in the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, probably a gesture from the military towards the Montreal Jewish community which had rallied so swiftly to the loyalist coalition under Colborne during the insurrections.

PAC, MG 30, D1, 8. PRO, WO 17/1542; 17/1544–46. G. B., Army, Report of the state trials, before a general court martial held at Montreal in 1838-9: exhibiting a complete history of the late rebellion in Lower Canada (2v., Montreal, 1839). Gentleman’s Magazine, January–June 1853: 200. [Charles] Grey, Crisis in the Canadas: 1838–1839, the Grey journals and letters, ed. W. G. Ormsby (Toronto, 1964). Daniel Lysons, Early reminiscences, with illustrations from the author’s sketches (London, 1896). Montreal Gazette, 13 Nov. 1838. Montreal Transcript, 21, 28 Sept. 1841. Quebec Gazette, 16 March 1838. Times (London), 16 Oct. 1852. Boase, Modern English biog., 1: 652. Desjardins, Guide parl. DNB. G.B., WO, Army list, 1838. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 406. Filteau, Hist. des Patriotes (1938–42). Elinor Kyte Senior, British regulars in Montreal: an imperial garrison, 1832–1854 (Montreal, 1981). B. G. Sack, History of the Jews in Canada, from the earliest beginnings to the present day, [trans. Ralph Novek] (Montreal, 1945). F. M. Greenwood, “L’insurrection appréhendée et l’administration de la justice au Canada: le point de vue d’un historien,” RHAF, 34 (1980–81): 57–93.

Cite This Article

Elinor Kyte Senior, “CLITHEROW, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clitherow_john_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clitherow_john_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elinor Kyte Senior |

| Title of Article: | CLITHEROW, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |