As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

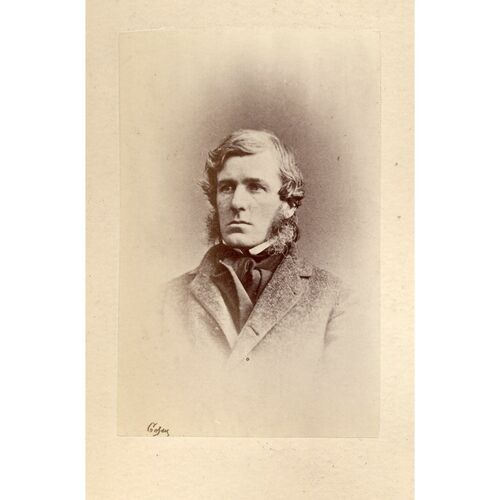

BILLINGS, ELKANAH, lawyer, journalist, official paleontologist of the Geological Survey of Canada, and member of the Natural History Society of Montreal; b. 5 May 1820 at Gloucester, U.C., son of Bradish Billings and Lamira Dow; d. 14 June 1876 at Montreal, Que.

The Billings family was Saxon by name and English by origin. It moved from New England into Canadian territory at the end of the 18th century, after the War of American Independence. Elkanah Billings was therefore the first of the line to be born in Canada. His maternal ancestors came from Wales; they had lived in the United States before establishing themselves in Canada with the loyalists.

Elkanah Billings was born on his father’s farm at Gloucester. At the gates of Ottawa, an urban centre named Billings’ Bridge recalls the site of the Billings’ family home. The second son of a family of nine children, but coming from a well-to-do and socially privileged environment, Billings received an extensive education. He first attended the schools at Gloucester and Bytown (Ottawa), then, after a break of four years, the St Lawrence Academy, at Potsdam, New York State. In 1839 he registered as a student at the Law Society of Upper Canada, and in the autumn of 1844 was allowed to practise law. On 31 July of the following year he married Helen Walker Wilson, the sister of a Toronto colleague.

The young lawyer carried on his profession, alone or in partnership with Robert Hervey, at Bytown until 1849, then at Renfrew. He returned to Bytown on 10 June 1852 and opened a new office. But he soon abandoned law and found his real vocation in geology and its auxiliary, paleontology. In the autumn of 1852 he apparently became editor of the Ottawa Citizen, a position he may have occupied until 1855. While he was publishing in the columns of the Citizen articles of a popular scientific nature relating to geology, and acquiring a basic knowledge of physics, trigonometry, and zoology, Billings was studying the fossils preserved in the rock formations along the banks of the Rideau River. At the same time he was collecting the Crinoidea, Cystoidea, and Asteroidea of which he was later to offer a rich collection to the museum of the Geological Survey of Canada.

On 7 Jan. 1854 Billings made his official début in the scientific world: he was appointed a member of the Canadian Institute of Toronto. In the same year he published his first paleontological study in the institute’s journal: “On some new genera and species of Cystidea from the Trenton limestone.” In 1855, for the universal exposition in Paris, he wrote an essay entitled Reddit ubi cererem tellus inarata quotannis, which won him a prize of $100. February 1856 was witness to an epoch-making event in the life of Billings and in the history of scientific research in Canada. The young paleontologist launched the first number of a monthly review, the Canadian Naturalist and Geologist, in which for 20 years he was to publish his scientific studies. He immediately won the admiration and support of experts, and particularly of Sir William Edmond Logan, the director of the Geological Survey of Canada. The latter applied to the Canadian government for the services of Billings, who on 1 Aug. 1856 became the official paleontologist for the surveys, with residence at Montreal. Except for a few months which he devoted to a study trip in England and Paris between February and June 1858, Billings spent the rest of his life studying and describing the fossils preserved in the museum of the survey. He communicated to researchers the results of his intelligent and persistent labour, namely 93 articles in the Naturalist, the official reports of the Geological Survey of Canada, and studies published by the Canadian Journal . . . , the American Journal of Science and Arts of New Haven, and the Geological Magazine of London.

At the time when Billings joined the Geological Survey of Canada in 1856, to become its first paleontologist, paleontology was a recent branch of knowledge. To appreciate his contribution to science, two things must be remembered: Georges Cuvier and Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck [Monet] had died 25 years earlier, and it was only three years later, in 1859, that Charles Darwin published On the origin of species by means of natural selection . . . , a work that was to revolutionize the contemporary scientific world. Billings was therefore a pioneer. He was not alone, however; other names were already adding lustre to the paleontology of invertebrates: Joachim Barrande, James Hall, Jacob Green, Carl Eduard von Eichwald, James de Carle Sowerby, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, and Roderick Impey Murchison, to mention only a few.

Billings had grasped immediately the importance of biology and geology for satisfactory work in paleontology. Moreover, he was a born naturalist, as is evidenced by his numerous monographs, particularly those describing recent animals, such as the bear, wolf, stag, otter, carcajou, caribou, lynx, beaver, and a number of birds. All these works appeared between 1855 and 1857. During the same years Billings also published numerous articles describing the fossils of Trenton (Ordovician), Potsdam (Cambrian), and Niagara (Silurian). He himself collected many of these fossils, including those of Trenton from the regions of Ottawa and Montreal, those of Niagara in the southwest of Ontario, and those of Potsdam from the border region near Montreal and the state of Vermont.

When one looks at Billings’ work, one is astonished at its extent. He has to his credit more than 200 articles, totalling some 3,000 pages. Among his important works must be cited some 500 pages of paleontology, which are contained in the famous Report of the Geological Survey presented by Logan in 1863 and known under the title of Geology of Canada, and his writings on the Paleozoic and Silurian fossils. It was the fossils of the Paleozoic age that he described in particular. To the description of the Silurian of Anticosti Island, which appeared about 25 years after Murchison’s authoritative work on the Silurian of Great Britain, and which W. H. Twenhofel was to utilize much later for his classic work on Anticosti Island, must be added those of the Silurian of Port-Daniel (Gaspé Peninsula, Quebec) and of Arisaig (Nova Scotia), and of the Devonian of Gaspé. If Billings described above all the fossils of the Paleozoic period and particularly those of the east of Canada, it was because Logan had first established its geology. However, Billings was not prevented from describing the corals of the Canadian west, or from touching on the Mesozoic period of British Columbia, and the Tertiary, even the Quaternary eras, when he described the mammoth and the mastodon. But in the case of the Paleozoic period he described fossils belonging to all zoological groups: brachiopods, cephalopods, pelecypods, gasteropods, trilobites, annelids, Bryozoa, echinoderms, Porifera, and Cœlenterata. He created hundreds of new species and dozens of new genera, consequently modern treatises on paleontology, particularly those of North America, quote him abundantly.

Billings always described new species and new genera in a concise and exact manner. Knowing what written material was available, he made all the necessary comparisons with the species already described and known, according to modern rules of the subject, but he also knew how to stress any truly distinctive feature. In dealing with the group of the echinoderms, when he described a whole new fauna of Crinoidea, Cystoidea, and Blastoidea, he perhaps best displayed his qualities as an observer and a scrupulously careful analyst. On occasion, he knew how to defend his opinions. When Addison E. Verrill and W. H. Niles, in a statement to the Boston Natural History Society, asserted that Billings had seen a family relationship between the genus Pasceolus, which he had created, and the Sphœronites, he replied: “Mr. Niles is quite mistaken in supposing that I ever believed in the Ascidian affinities of the Sphaeronitidae. I was the first to point out the occurrence of that family in the palæozoic rocks of America. I discovered and described the genera Comarocystites, Amygdalocystites and Malocystites. In all that I have written on the subject I cannot find a single remark from which it could be supposed that I ever entertained such an idea.”

He was conscious of very modern problems in paleontology, such as one related to systematics. “I think . . . the number of species is becoming so great that, sooner or later, Conocephalites will be broken up into a number of genera.” He was already giving thought, therefore, to the tendencies of what are called, in the jargon of the science, the “lumpers” and the “splitters.” Finally, he concerned himself with stratigraphic correlations and synchronism, for example when he compared the Silurian of Anticosti Island with that of Great Britain, or the calcareous rocks of Pointe de Lévy with the groups of Potsdam (Cambrian), Chazy, and Black River.

Elkanah Billings died on 14 June 1876 at Montreal, after suffering for three years from a severe illness, Bright’s disease. His name was known to the scientific world: he had been a member of the Geological Society of London since 1858, and had been awarded medals by the International Exhibition of London in 1862 and by the Natural History Society of Montreal and the universal exposition in Paris in 1867. The journal Billings had founded, which he had kept supplied with his scientific studies for 20 years, survived him. An achievement that his critical eye, his researcher’s mind, and his love of science and of the soil of Canada had rendered imposing and durable continued to perpetuate his memory.

In his report for 1876–77, the director of the Geological Survey of Canada, Alfred Richard Cecil Selwyn*, underlined Billings’ disappearance thus: “. . . the country has . . . been deprived of the services of one who had for more than twenty years ably and efficiently fulfilled the duties of this important branch [paleontology] of the Geological Survey.”

A complete list of Billings’ writings while he was a member of the Geological Survey of Canada will be found in D. B. Dowling, General index to the reports of progress, 1863 to 1884 (Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, 1900). However, his most important works are the following: Elkanah Billings, Catalogues of the Silurian fossils of the Island of Anticosti, with descriptions of some new genera and species (Geological Survey of Canada, Montreal, London, New York, and Paris, 1866); Palaeozoic fossils (2v., Montreal, 1865–74). Canadian Naturalist, (Toronto and Montreal), 1856–76. [Logan et al.], Geology of Canada.

Canada, Geological Survey, Report of progress for 1876–77 (Montreal, 1878). Gazette (Montreal), 15 June 1876. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire, I, 185. R. I. Murchison, The Silurian system, founded on geological researches in the counties of Salop, Hereford, Radnor, Montgomery, Caermarthen, Brecon, Pembroke, Monmouth, Gloucester, Worcester, and Stafford; with descriptions of the coalfields and overlying formations (2v., London, 1839). W. H. Twenhofel, Geology of Anticosti Island (Geological Survey of Canada Memoir, 154, Ottawa, 1927). H. M. Ami, “Brief biographical sketch of Elkanah Billings,” American Geologist (Minneapolis), XXVII (1901), 265–81. J. F. Whiteaves, “Obituary notice of Elkanah Billings, F.G.S., paleontologist to the Geological Survey of Canada,” Canadian Naturalist and Quarterly Journal of Science (Montreal), new ser., VIII (1878), 251–61.

Cite This Article

Andrée Désilets and Yvon Pageau, “BILLINGS, ELKANAH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/billings_elkanah_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/billings_elkanah_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrée Désilets and Yvon Pageau |

| Title of Article: | BILLINGS, ELKANAH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |

![[Elkanah Billings, F.R.G.S.] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Elkanah Billings, F.R.G.S.] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.4077.jpg)