As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

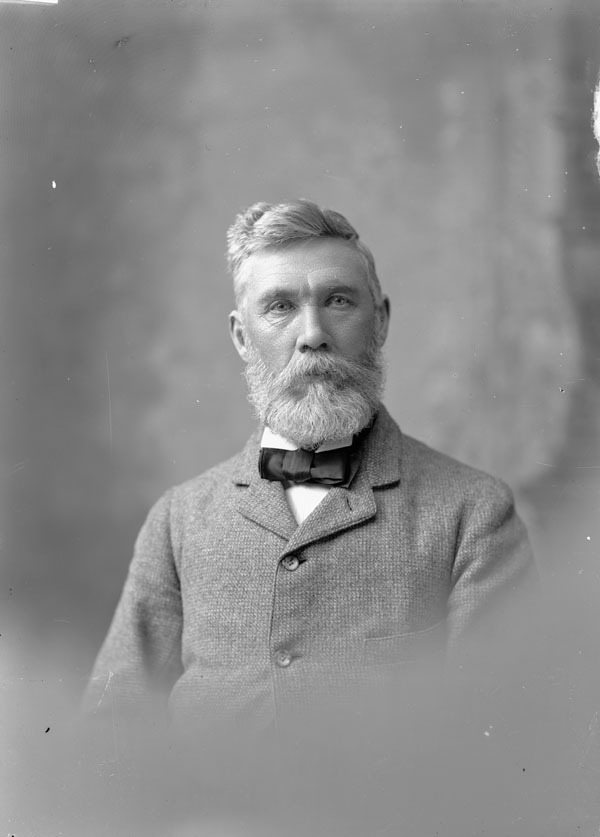

EWART, DAVID, civil servant and architect; b. 18 Feb. 1841 in Penicuik, Scotland, third son of John Ewart, a builder, and Jean Cossar; m. first 20 March 1871 Jeanne Marie Doyen (d. 11 Dec. 1885) in York, England, and they had five sons and one daughter; m. secondly 19 May 1887 Annie Sigsworth Simpson (d. 13 June 1938) in Ottawa, and they had four daughters and two sons; d. there 6 June 1921.

David Ewart was born and educated in Penicuik, south of Edinburgh. He apprenticed as a joiner in his father’s construction firm, learned architectural drawing from Edinburgh architect Walter Carmichael, and apparently studied architecture at the School of Arts in Edinburgh. By the late 1860s he was employed in Helperby, England, as clerk of works for the Myton Hall estate. In April 1871, at the age of 30 and recently married, he set sail for Canada, armed with testimonials from architects Joseph Taylor, Thomas Dickinson, and James Aitken attesting to his excellent drafting skills and industrious work habits. A friend in Montreal advised him to seek employment with the Department of Public Works in Ottawa. He approached Frederick Preston Rubidge*, the department’s assistant engineer and architect, who at that moment happened to be looking for an architectural assistant. On 16 May, only 11 days after arriving in Canada, Ewart was hired on a trial basis at $60 per month.

The engineering and architecture functions of the Department of Public Works were separated in the spring and summer of 1871. Rubidge was superannuated to make room for two new appointees, George-Frédéric-Théophile Baillairgé* as assistant chief engineer and Thomas Seaton Scott* as senior architect (a title that would be changed the following year to chief architect). In October 1871 Scott mapped out a plan for staffing his new office, envisioning a range of positions from “a thoroughly competent head assistant” to a draftsman for tracing. He had Ewart in mind as a “practical draughtsman,” one of the mid-level positions. Nevertheless, by January 1875 Ewart had become the highest-paid architectural draftsman in the office, and by 1879 he was de facto assistant chief architect.

In October 1881, ten years after being hired on trial, Ewart gained the office’s top position – albeit on an acting basis – when his minister, Sir Hector-Louis Langevin*, orchestrated Scott’s resignation-cum-retirement. At the very same moment, however, Thomas Fuller*, one of the original architects of the Parliament Buildings and then living in upstate New York, was corresponding with Samuel Keefer*, a former deputy commissioner of public works in Ottawa, to promote his candidacy as the department’s new chief architect. Keefer’s strong endorsement of Fuller was quickly acted on by Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald*, and Fuller was in place by December. Ewart reverted to his role as assistant chief architect.

Known for his business capacity, Ewart took care of a considerable amount of Fuller’s work, including office supervision and correspondence. In addition, he managed the auditing of accounts for all public buildings controlled by the federal government – the responsibilities of the chief architect’s office, unlike those of a private architectural practice, included acquisition, maintenance, and repair. The department’s deputy minister, Antoine Gobeil, singled out Ewart in 1892 as “the mainstay of the chief architect’s office. I never knew a man to work so much. He works day and night.”

Fuller retired in 1896, and approval to appoint Ewart as chief architect was finally given on 2 Nov. 1897. More than 340 new buildings and substantial renovations would be undertaken during his tenure of this office, one of the most productive eras in the history of the chief architect’s branch. The office produced a steady string of well-designed public buildings – almost every municipality of any consequence got one – and the standardized plans that emerged in this period resulted in a recognizable federal design vocabulary across the country. Ewart and his staff occasionally equalled the best work being produced in private practice, as in their Edwardian baroque design for the Vancouver Post Office (1905–10). Ewart himself designed in a very controlled, sober manner, favouring Tudor Gothic for his Dominion Archives Building (1904–6), Victoria Memorial Museum (1905–8), Royal Mint (1905–8), and Connaught Building (1913–16), all in Ottawa.

Ewart’s otherwise successful tenure as chief architect was not without low points. For example, the department (and therefore the chief architect) was found partly responsible for the collapse of an addition to the west block on Parliament Hill, and 80 feet of the central tower of the Victoria Memorial Museum had to be removed after it began to sink. The edifice Ewart thought one of his best, the Connaught Building, was criticized by his peers in the journal Construction (Toronto) as being of “puerile design and questionable construction.”

In 1903 Ewart was awarded the Imperial Service Order (one of the first in Canada) in recognition of his career in the civil service. He was also a member of the first executive council (1889) and president (1893) of the Ottawa Institute of Architects, a founding member (1889) and councillor (1891) of the Ontario Association of Architects, and a founding member and councillor (1907) of the Institute of Architects of Canada (later the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada). He retired in 1914 at age 73, but was immediately made dominion consulting architect, a position created specifically for him and one that he held at full salary until his death. A singular devotion to the Canadian civil service came to an end 50 years after it had begun when he died of a stomach malignancy at his home in Ottawa (not, as legend has it, by hurling himself from his truncated museum tower). Four of his sons worked in architecture or engineering. The eldest, John Albert, practised for 65 years, and at his death in 1964 was considered the doyen of Ottawa’s architects.

David Ewart had attained the chief architect’s office at a time when the position had, by dint of scope and volume of work, evolved from one requiring a master designer – a role so ably played by his predecessor Fuller – to one needing a master administrator. He was ideal for this work, efficiently orchestrating a sizeable office of architectural specialists to produce a high volume of very competent (and occasionally outstanding) construction within a politically demanding context. Professionally, Ewart was a capable architect of buildings; more significantly, he was an accomplished architect of the process of building.

The author wishes to thank Helen M. Lyons of Ottawa, and Susan Taylor of Vancouver, the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of the subject, respectively, for providing access to some Ewart family papers.

AO, RG 80-5-0-148, no.2023; RG 80-8-0-809, no.10392. GRO, Reg. of marriages, All Saints North Street, York, 20 March 1871. LAC, RG 11, B1(a), 591; B1(b), 725, 753; B3(a), 2922; RG 31, C1, 1901, Nepean, Ont., dist.52: 11; RG 76, C: 1(a) (mfm.). National Arch. (G.B.), HO 107 1841, Penicuik, Edinburgh County. Globe, 27 Aug. 1901. Ottawa Citizen, 3 Oct. 1881, 7 June 1921. Ottawa Evening Journal, 7 June 1921. Toronto Daily Star, 23 June 1906. Margaret Archibald, By federal design: the chief architect’s branch of the Department of Public Works, 1881–1914 (Ottawa, 1983). Can., Dept. of the Secretary of State, The civil service list of Canada . . . (Ottawa), 1898–1914; Parl., Sessional papers, 1892, no.16C: 487; 1906, no.161: 1–6. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). “A competent chief architect and representative government buildings the most pressing need in Canada’s advancement,” Construction (Toronto), 5 (1911–12), no.1: 43–44. “Proposed department building, Ottawa – a gross breach of faith with architectural profession – a beautifully symmetrical and monumental adaptation of Gothic set aside for a design characterized by critic as a ‘glorified packing box,’” Construction, 3 (1910), no.6: 72–73. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. Who’s who and why, 1915/16. Janet Wright, Crown assets: the architecture of the Department of Public Works, 1867–1967 (Toronto, 1997).

Cite This Article

Gordon W. Fulton, “EWART, DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ewart_david_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ewart_david_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon W. Fulton |

| Title of Article: | EWART, DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |