Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

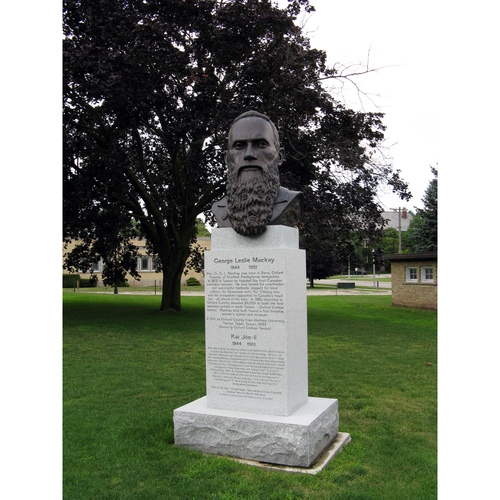

MACKAY, GEORGE LESLIE, educator, Presbyterian missionary, dentist, anthropologist, and author; b. 21 March 1844 in Zorra Township, Upper Canada, youngest of six children of George MacKay, a farmer, and Helen Sutherland; m. May 1878 Tui Chang-mia, and they had a son and two daughters; d. 2 June 1901 in Tamsui (Tanshui, Republic of China).

Raised in an Oxford County community that had been transported virtually intact from Sutherlandshire, Scotland, George Leslie Mackay inherited both the martial spirit of his grandfather, who had fought at Waterloo, and the strict Calvinist Presbyterianism which produced a host of ministers in the MacKay clan. After primary education in Zorra and at the Woodstock Grammar School, he taught for two years, and then in 1865–67 took arts at Knox College, Toronto, where he gained a reputation as a diligent eccentric. “He sometimes lost control of himself and became painfully violent. . . . He could scarcely be described as social,” recalled kinsman Robert Peter MacKay, later secretary of the Foreign Missions Committee of the Presbyterian Church in Canada (Western Division). After graduating from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1870, Mackay took postgraduate studies in Edinburgh under Alexander Duff, the famous missionary “apostle to India.”

While in Scotland, Mackay was designated by the FMC in Canada as its first foreign missionary, to China. The Presbyterian Church was not fired with missionary zeal, and many ministers regarded him as “an excited young man”; he in turn placed them in the “ice age” of the church. He was ordained on 19 Sept. 1871 and left Toronto one month later, “like Abraham, not knowing whither he went.” His passport was his inscribed Bible. After six months visiting the English Presbyterian missions in the Chinese port of Shantou and in south Formosa, he “occupied” his field, the northern half of the island. Setting up headquarters in a stable in the port of Tamsui, he wrote, “Here I am in this house, having been led all the way from the old homestead in Zorra by Jesus, as direct as though my boxes were labelled, ‘Tamsui, Formosa, China.”‘

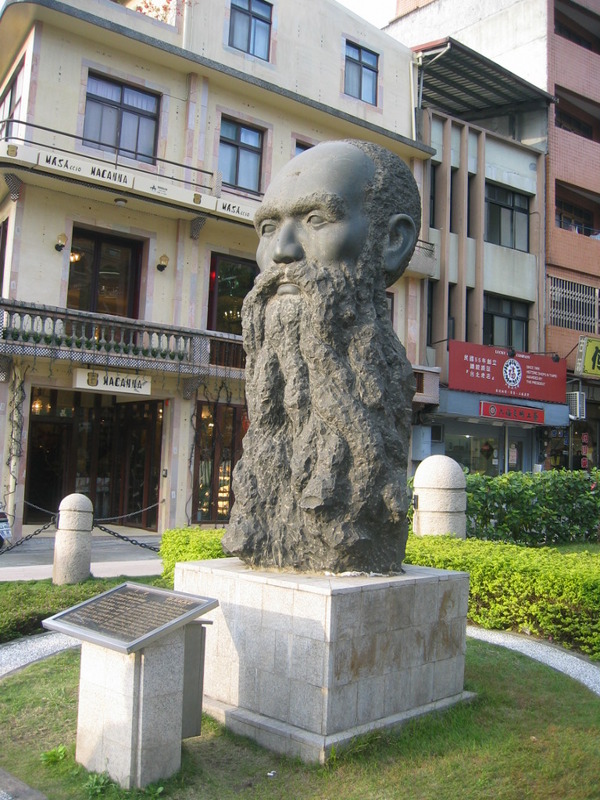

From the beginning Mackay avoided the small European community, preferring the company of herdsboys, who taught him the language of the common people. Within a month he had made his first convert, an educated Chinese named Giam Cheng-hoa, known to Canadians as A Hoa, who became his constant companion and official assistant. Gradually they gathered a “peripatetic school” of trainees who would travel through the mountain villages in a procession headed by Mackay with his pith helmet and long black beard.

In Formosa, as in the missions in mainland China, Mackay faced unremitting hostility from the xenophobic Chinese, particularly the scholar gentry, who would foment riots to evict him. Consequently his early converts were illiterate, rural outcasts, considered as traitors to their country and to their families for giving up their ancestral religion. Mackay made perilous trips into the mountains to convert the headhunters, but only among the Pe-po-hoan, the Sinicized aboriginals who saw the missionary as a potential protector, did he have any success. In order to attract people, he developed what other missionaries described as “peculiar” methods, the most distinctive of which was itinerant dentistry. He and his helpers would take their stand in an open place and, after singing and preaching, offer to extract teeth loosened by tropical diseases. “The Bible and the forceps went together,” Mackay later stated, claiming he had extracted 40,000 teeth in 30 years. By 1888 he had 16 chapels and 500 converts among the native Taiwanese. This attainment, of course, made him doubly suspect to the Chinese, and later the Japanese, officials.

Another example of Mackay’s “going native” was his marriage to a Pe-po-hoan, which caused considerable controversy in Canada and in the foreign community on Formosa. Noting that few native women attended mission services, Mackay hoped his marriage would open their hearts and homes. He never thought about marrying a Canadian, he wrote in defence of his actions, “I am thinking how I can do most for Jesus.” Minnie Mackay, as she was prosaically called, proved to be a power in the mission. During the Mackays’ furlough in Canada in 1881–82 – his first in ten years – she helped raise $6,125 in Oxford County for the construction of Oxford College in Tamsui. It opened to great fanfare, and was soon part of a complex of residences, school buildings, a church, and a hospital that would not have been out of place in small-town Ontario. Mrs Mackay became matron of the girls’ school.

Mackay’s relations with his fellow Canadian missionaries show his dark side. The qualities that made him a missionary entrepreneur also constituted an explosive egomania, and his dealings with the first three of his associates were marked by discord. The FMC was led to question “whether Dr Mackay is in his right mind. . . . Who counts the teeth he pulls, and what [do] those thousands of teeth carefully treasured have to do with counting up spiritual results?” Only William Gauld, the fourth colleague, managed without friction, and he became Mackay’s chosen successor.

During the French blockade of Formosa in the undeclared Sino-French war of 1884–85, the Chinese took advantage of Mackay’s evacuation to attack the Christians and demolish the chapels. On his return Mackay demanded “ten thousand Mexican dollars” in compensation, enough to build imposing stone churches with steeples that would tower over the one-storey village houses. “We cannot stop the barbarian missionary,” the people complained.

In trips throughout his tropical isle, Mackay gathered specimens of local flora and fauna, which formed the basis of a museum at Oxford College. Other artefacts collected by Mackay on Formosa became part of the collections of the ethnology department of the Royal Ontario Museum. From far Formosa: the island, its people and missions, which he wrote during his second – and last – furlough in 1894–96, is typical of the best missionary ethnography: pious denunciations of heathenism mixed with vivid descriptions of local history, geography, and native customs, all told as a thrilling adventure story.

During his first furlough Mackay had been granted an honorary dd by Queen’s College, Kingston; in his second he was elected to the highest honour the church could bestow, moderator of the General Assembly. The “ice age” had thawed, and the Presbyterian Church now had missions in China, India [see Agnes Maria Turnbull], Trinidad, and the Canadian west. Mackay, as the church’s pioneer foreign missionary and a diligent propagandist, was in large part responsible for this new missionary enthusiasm. While he was in Canada in the 1890s, Japan annexed Formosa. Although Mackay at first welcomed the Japanese – any government was better than the Chinese – their presence complicated mission matters because Japanese was now the official language. Despite their overt friendliness, the Japanese saw Mackay’s mission as a Chinese, and therefore potentially subversive, institution. “Hatred for the Japanese,” Mackay wrote, “induced friendliness to the religion of the foreigner.”

Although Mackay had suffered from meningitis and malaria, he died in 1901 of throat cancer. For 30 years, Mackay, along with A Hoa and Minnie Mackay, had virtually constituted the north Formosan mission. He proved that one missionary could run an educational, medical, and evangelistic mission on a “shoe-string budget,” aided by an army of paid evangelists and female catechists (in his case, at 60 stations). Until 1949 Canadian Presbyterians were the only Protestant missionaries in the north half of Formosa. Mackay remains important in the history of Formosa as a founder of modern schools and hospitals there. His name lives on through the Mackay Memorial Hospital in T’aipei, one of the most important on the island. The original building of Oxford College is now a museum dedicated to the life of George Leslie Mackay, “the black bearded barbarian.”

George Leslie Mackay’s book, From far Formosa: the island, its people and missions, edited by James Alexander Macdonald*, was published at Toronto in 1896 (copyright 1895) and went through several editions.

NA, RG 31, C1, East Zorra Township, pt.1, dist.1: 19 (mfm. at AO). Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto), Ethnology dept., artefacts collected by G. L. Mackay in Formosa. UCC-C, 122/7; Biog. file; Photograph Coll. A. J. Austin, Saving China: Canadian missionaries in the Middle Kingdom, 1888–1959 (Toronto, 1986). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). A. H. Ion, The cross and the rising sun: the Canadian Protestant missionary movement in the Japanese empire, 1872–1931 (Waterloo, Ont., 1990). James Johnston, China and Formosa: the story of the mission of the Presbyterian Church of England . . . (London, 1897). Marian Keith [M. E. Miller (MacGregor)], The black bearded barbarian: the life of George Leslie Mackay of Formosa (Toronto, 1912). R. P. MacKay, Life of George Leslie Mackay, d.d., 1844–1901 (Toronto, 1913). Some things that should be known to the ladies of the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society in Canada (14-page pamphlet, Hong Kong, 1888; copy in UCC-C, 122/7, file 15).

Cite This Article

Alvyn J. Austin, “MACKAY, GEORGE LESLIE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackay_george_leslie_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackay_george_leslie_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alvyn J. Austin |

| Title of Article: | MACKAY, GEORGE LESLIE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |