As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

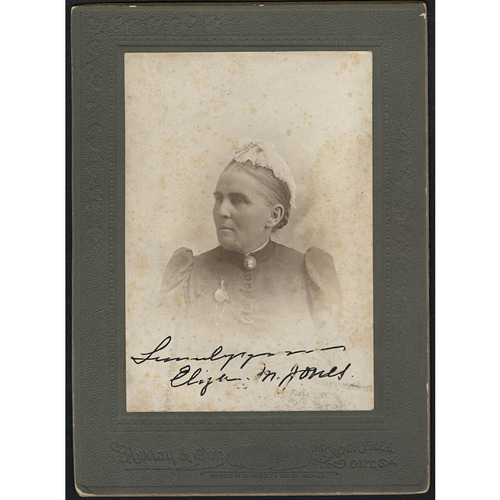

HARVEY, ELIZA MARIA (Jones), farmer, breeder, butter producer, and author; b. 24 Dec. 1838 in Maitland, Upper Canada, daughter of Robert Harvey and Sarah Glassford; m. 29 Nov. 1859, in Brockville, Upper Canada, Chilion Jones, son of Jonas Jones*, and they had three sons and four daughters; d. 6 April 1903 in Gananoque, Ont., and was buried in Brockville.

The second eldest daughter of a prominent miller, Eliza Harvey was educated in Montreal and Scotland. The premature death of her mother forced her to stay home and care for five younger brothers and sisters. It was probably on her father’s farm that she first developed her pioneering interest in dairying and animals.

In 1859 Eliza married Chilion Jones, a member of a prominent loyalist family in Brockville. The young couple moved to Ottawa, where Chilion, an architect and engineer, was working on the new Parliament Buildings [see Thomas Fuller*]. Following this project, they returned to their home, Brockville, where they had a small piece of property on the edge of town. In addition to bearing four children in the 1860s, Eliza started a small dairy operation. The property consisted of only a few acres, but she rented two small farms nearby. At first she acquired grade cattle and sold the small amount of butter they produced locally. Jones stated that it was her purchase of an outstanding Jersey-cross cow in 1873 that prompted her to breed purebred Jersey cattle. It was an inspired decision since at this time in Ontario the ideal cow was considered to be a dual-purpose animal (usually grade), which could produce both milk and beef. Jerseys were derided as small and wasteful, unfit for beef and producing an insignificant amount of cream-rich milk. Jones, though, was impressed with the quality of the butter that could be made from their milk. Over the next few years, through “hard experience,” she learned how to make rich, perfect butter at a time when much Ontario butter was judged to be fit for use only as axle grease. Most butter was produced on farms by women under difficult and often unsanitary conditions. Usually only a small amount would be made on each farm and sold to local storekeepers, who in turn sold it to customers or packed it for export, generally without regard to freshness or colour and often in dirty containers. Jones, however, prepared her butter under the cleanest conditions, sold it at a premium price to many prestigious clients in Canada and the United States, and by the 1890s was shipping over 7,000 pounds a year. Among her customers in Canada were the Rideau Club in Ottawa and the dining-cars of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Jones’s initial purchase of purebred Jerseys had been from Romeo H. Stephens of Montreal, a family friend who had established at Saint-Lambert the first noted herd in Canada with animals obtained from the Royal Herd at Windsor. With this good breeding stock as a base, she built up a large herd. Her farm was a model of “scientific agriculture” where the cattle were housed in a gas-lit barn, which also featured a steam engine to power equipment. The Jerseys were fed a carefully balanced ration to help them produce the maximum amount of milk. To help with the labour, Jones employed three men but she personally oversaw all aspects of the farm, from keeping the books to supervising the butter operation. Her husband, who had little to do with the farm, appears to have been absent much of the time managing his brother’s shovel factory in Gananoque.

In the 1880s Mrs Jones began to exhibit her cattle at fairs and exhibitions in Ontario, Quebec, and New York State. Her efforts met with unmitigated success. Her first major prize was the breeders’ cup offered by the New York cattle dealers Kellog and Company in 1886. In 1889 the Farmer’s Advocate and Home Magazine of London, Ont. [see William Weld*], put up a prize for the best three dairy cattle in the province and Jones’s Jerseys won handily. In addition, her cattle won prizes at major fairs and exhibitions in Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto, and Kingston, despite her feeling, as she wrote in 1890, that she could not “devote nearly as much time to my cattle as is supposed for my domestic and family affairs must always come first, and for this reason, [I] often find it impossible to exhibit at all.”

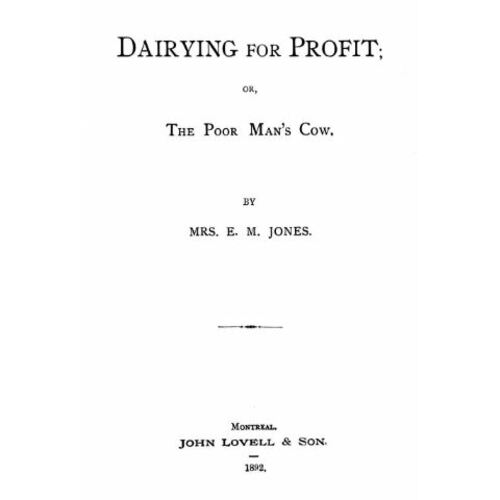

Eliza Jones sold stock to individuals and institutions all over North America, including the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph, which had an important demonstration herd. She was a member of the Canadian Jersey Cattle Breeders’ Association and a frequent contributor to agricultural periodicals such as the Farmer’s Advocate. In the winter of 1891–92 she contributed a series of articles on dairying to the Family Herald and Weekly Star of Montreal. In response to the many letters she received, she decided to collect and supplement the columns and publish them. The book, Dairying for profit: or, the poor man’s cow (Montreal, 1892), was dedicated by Jones to “the farmers’ wives of America . . . my sisters in toil.” It was an outstanding success, with over 50,000 copies alone purchased by the Ontario Department of Agriculture. The Farmer’s Advocate gave away copies as a subscription bonus and advertised it as the “best book ever written.” Jones’s fame was probably a factor in her selection as a judge of butter at the Columbian exposition in Chicago in 1893. Four years later she was hailed by the Toronto periodical Farming as the “best known dairywoman on the continent.”

In 1896, after most of her rented farmland was sold, Mrs Jones had disposed of half her herd to Benjamin Heartz of Charlottetown. She retained some of the cattle to “supply her own family.” Never one to remain inactive, however, she then devoted herself to raising and selling carriage horses and racehorses. She also began to write short stories and “light literature,” which she published in the Farmer’s Advocate.

In the fall of 1902 Jones travelled to Gananoque to be with her husband, who was in poor health. While there, she fell ill and died. She was thorough to the end: after her death the rest of her herd of Jerseys was sold at prices she had already placed on them. She was survived by her husband and by two sons and three daughters, one of whom, Elsie, was a noted horsewoman.

Further editions of Eliza M. [Harvey] Jones’s Dairying for profit: or, the poor man’s cow were published at Chicago in 1893 and Montreal in 1894; a French translation, Laiterie payante: ou, la vache du pauvre, appeared at Trois-Rivières, Qué., in 1894. She is also the author of an eight-page pamphlet, Lecture on co-operative dairying and winter dairying (Montreal, [1893]).

AO, RG 8, 1-6-B, 28: 32; RG 22, ser.179, no.3505. NA, RG 31, C1, 1871, Brockville, Ont., East Ward (mfm. at AO). Evening Recorder (Brockville), 7, 11 April 1903. Farmer’s Advocate and Home Magazine, 1890–1903. Globe, 7 April 1903. Ruth McKenzie, “Eliza Jones – Canada’s pioneer dairywoman,” Family Herald (Montreal), 25 Jan. 1968: 39–40. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Chadwick, Ontarian families, 1: 176. The dairy industry in Canada, ed. H. A. Innis (Toronto, 1937). Farming, 14: 435. R. L. Jones, History of agriculture in Ontario, 1613–1880 (Toronto, 1946; repr. Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1977). J. W. G. MacEwan, The breeds of farm live-stock in Canada (Toronto, 1941). Ontario Geneal. Soc., Leeds and Grenville Branch, Brockville cemeteries: St. Peter’s Anglican and the Old Catholic (Brockville, [1986]). Ralph Selitzer, The dairy industry in America (New York, 1976). Types of Canadian women (Morgan).

Cite This Article

S. Lynn Campbell and Susan L. Bennett, “HARVEY, ELIZA MARIA (Jones),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harvey_eliza_maria_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harvey_eliza_maria_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. Lynn Campbell and Susan L. Bennett |

| Title of Article: | HARVEY, ELIZA MARIA (Jones) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |