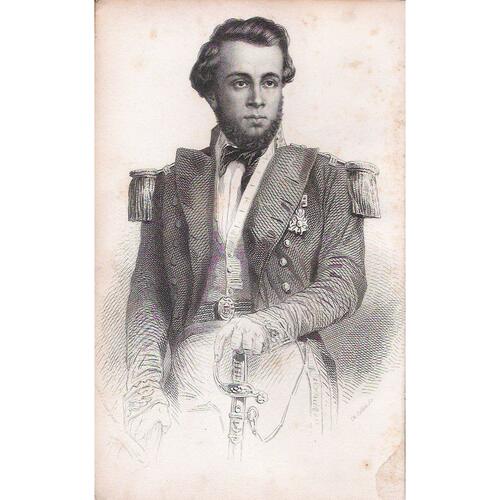

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BELLOT, JOSEPH-RENÉ, naval officer, explorer, and author; b. 18 March 1826 in Paris, one of about seven children of Étienne-Susanne-Zacharie-Brumaire Bellot, a smith and farrier, and Adélaïde-Estelle Laurent; d. unmarried 18 Aug. 1853 in Wellington Channel (N.W.T.).

The Bellot family moved from Paris to Rochefort when Joseph-René was five years old. He did well in school and his teacher, impressed by his talent, persuaded the mayor that the municipality should subsidize his entry into the college at Rochefort, where he received an education that would have been beyond his father’s limited means. The city of Rochefort continued to support him financially when, on 10 Nov. 1841, he entered the École Navale at Brest. He passed out from there on 1 Sept. 1843 and spent the following six months aboard vessels in the port of Brest.

In June 1844 Bellot embarked as naval cadet on the corvette Berceau for a voyage to the Indian Ocean. During this tour of service he was seriously wounded in a joint Anglo-French naval strike against the port of Tamatave in Madagascar on 15 June 1845, and for his part in this action he was nominated a knight of the Legion of Honour on 2 Dec. 1845. After a brief service aboard the frigate Belle-Poule in 1846, Bellot returned to France and was promoted sub-lieutenant on 1 Nov. 1847. Following a two-year tour of duty aboard the corvette Triomphante he returned to Rochefort on 25 Aug. 1850.

During a period of inactivity following his return to France, Bellot developed an interest in the search for Sir John Franklin*, lost in the Arctic since 1845. Until 1850 the search efforts had been sustained exclusively by the English-speaking world and Bellot felt that the concern of the French, and of seamen everywhere, should also be demonstrated. In mid March 1851 he wrote letters to Lady Franklin [Griffin*], who was then organizing her second private search expedition, and to William Kennedy*, the Canadian fur trader who was to command it, expressing his sympathy and volunteering his services. His application, though strongly supported by his own superiors and by the French ambassador in London, was at first opposed by Lady Franklin’s advisers at the Admiralty, who had misgivings that the presence of a foreign officer on a British ship might lead to problems of discipline and rank. Kennedy, on the other hand, favoured Bellot’s appointment, if only for his skills as a navigator. Finally, on 1 May, shortly before the search vessel, Prince Albert, was due to sail, he and Lady Franklin sent Bellot a cautious invitation to meet them.

Bellot impressed Lady Franklin at once and she confirmed his appointment after their first interview. Moreover, by the time the ship sailed from Stromness, in the Orkney Islands, on 3 June 1851, he had won the confidence and affection of all around him. Franklin’s niece, Sophia Cracroft, wrote that “we are really very fond of him – his sweetness & simplicity & earnestness are most endearing.”

The apprehension voiced by Lady Franklin’s advisers was further dispelled when the expedition reached the Arctic, for Bellot had an early opportunity to demonstrate his authority over the British crew in Kennedy’s absence. On 9 September Kennedy took a small landing party ashore at Port Leopold, on the northeast coast of Somerset Island (N.W.T.), and during his absence the ice carried the ship away to the south. Failing in his efforts to hold the ship in the vicinity of Port Leopold, Bellot was forced to put into Batty Bay, about 50 miles to the south, from which point he immediately set out on foot with a rescue party. Bad weather forced him to return to the Prince Albert, where preparations were made for another attempt. After a second failure Bellot finally led a successful rescue party overland to Port Leopold and back in mid October.

Kennedy began his sledging operations on 5 Jan. 1852. Bellot accompanied him on a preliminary outing to Fury Beach, and they were again together on the expedition’s main sledge journey, leaving on 25 February. This trek of 1,100 miles was one of the longest accomplished during the Franklin search. They travelled south to Brentford Bay, where they discovered Bellot Strait, separating Somerset Island from Boothia Peninsula. Having reached Peel Sound, Bellot and Kennedy continued west and crossed Prince of Wales Island before making their way back to Peel Sound and heading north to Cape Walker. Returning to the Prince Albert, they followed the north and east coasts of Somerset Island back to Batty Bay, arriving on 30 May. This journey, particularly the discovery of Bellot Strait which revealed the northernmost point of the American continent, was the highlight of the expedition. On 6 August they set sail for Great Britain. Having made a brief stop at Beechey Island, the Prince Albert arrived safely at Aberdeen on 7 October.

The voyage had entirely vindicated Kennedy’s initial support for Bellot. He had brought with him all the “vivacity, intelligence & good humour of a French officer” for which Kennedy had hoped, and their combined skills in sledge travel and navigation had made them excellent travelling companions. Bellot’s participation in the expedition was also widely acclaimed as a symbol of Anglo-French friendship; he was named a foreign corresponding fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and upon his return to France he learned of his promotion to lieutenant, dated 3 Feb. 1852. From Paris he maintained a regular correspondence with Lady Franklin, whom he now regarded with almost filial affection, telling her of his efforts to persuade his own government to send out a search expedition. Those efforts having failed, he sent Lady Franklin a request, on 1 April 1853, to join Captain Edward Augustus Inglefield’s Phoenix expedition and upon her recommendation was accepted by the Admiralty without question.

Inglefield was to deliver supplies and dispatches to Sir Edward Belcher*’s search expedition of five ships, then wintering at various sites in the Arctic. The Phoenix reached one of the ships, the supply vessel North Star, at Beechey Island on 8 Aug. 1853, and four days later Bellot set off on foot with four men to deliver messages to Belcher, then in Wellington Channel. On 17 August Bellot and two of the men drifted away from the shore on an ice floe. They made a shelter for the night and the next morning Bellot went out to examine the ice. One of the men went out to join him, but found only his stick on an adjacent floe; Bellot had apparently fallen between floes and drowned.

During Bellot’s short period of Arctic service, his simple kindness and energetic devotion to a foreign cause had inspired the deep affection of Lady Franklin, the admiration of Kennedy, and the trust and friendship of all his shipmates. When news of his death reached Europe, that same affectionate esteem was demonstrated by a much wider community. Subscribers on both sides of the Channel, led by the personal initiative of Emperor Napoleon III, contributed to the financial relief of his impoverished family; the city of Rochefort erected a memorial to him; and his many admirers in Britain raised an obelisk in his honour outside Greenwich Hospital, on the south bank of the Thames. Bellot’s narrative of the 1851–52 expedition, Journal d’un voyage aux mers polaires, was published posthumously in 1854 and was followed, in 1855, by an English translation.

Joseph-René Bellot is the author of Journal d’un voyage aux mers polaires exécuté à la recherche de sir John Franklin, en 1851 et 1852 . . . précédé d’une notice sur la vie et les travaux de l’auteur par M. Julien Lemer (Paris, 1854; nouv. édit., Oxford, 1907), an English translation of which was published under the title Memoirs of Lieutenant Joseph René Bellot . . . with his journal of a voyage in the polar seas, in search of Sir John Franklin, [ed. Julien Lemer] (2v., London, 1855). Another French edition later appeared under the title Voyage aux mers polaires à la recherche de sir John Franklin . . . , intro. Paul Boiteau (Paris, 1880).

Scott Polar Research Institute (Cambridge, Eng.), ms 248/107, 1 March–30 May 1851; ms 248/247/23, 30 May–4 June 1851; ms 248/348/1–5, 1852–53; ms 248/349, 30 Oct. 1852; ms 887; “Encyclopedia arctica,” ed. Anne Fraser and Mical O’Maher (ms, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1974) (mfm.). G.B., Parl., Command paper, 1854, 42, [no.1725]: 101–331, Papers relative to the recent Arctic expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin and the crews of H.M.S. “Erebus” and “Terror.” William Kennedy, A short narrative of the second voyage of the “Prince Albert,” in search of Sir John Franklin . . . (London, 1853). Memoir of the late Lieutenant Bellot . . . to accompany his engraved portrait; from the original picture, painted expressly for Lady Franklin, by Stephen Pearce, and engraved by James Scott (London, 1854). Maurice Hodgson, “Bellot and Kennedy; a contrast in personalities,” Beaver, outfit 305 (summer 1974): 55–58. Mary Kennedy, “Lieutenant Joseph René Bellot, knight of the Legion of Honour,” Beaver, outfit 269 (June 1938): 43–45. F. J. Woodward, “Joseph René Bellot, 1826–53,” Polar Record (Cambridge), 5 (January 1947–July 1950): 398–407.

Cite This Article

Clive Holland, “BELLOT, JOSEPH-RENÉ,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 7, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bellot_joseph_rene_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bellot_joseph_rene_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clive Holland |

| Title of Article: | BELLOT, JOSEPH-RENÉ |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | April 7, 2025 |