As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

BAIRD, NICOL HUGH, engineer and inventor; b. 26 Aug. 1796 in Glasgow, son of Hugh Baird and Margaret Burnthwaite; m. 21 Sept. 1831 in Montreal Mary White, daughter of Andrew White*, and they had four sons and four daughters; d. 18 Oct. 1849 in Brattleboro, Vt.

Relatively little is known about Nicol Hugh Baird’s early life. At about the age of 16 he went to Russia where he spent several years with his uncle Charles Baird, founder of a machinery works at St Petersburg. Around 1816 Nicol returned to Scotland where he continued his training under his father, a canal engineer and builder. Following Hugh Baird’s death in 1827, Nicol unsuccessfully sought a situation in the army and an appointment as a surveyor. In the spring of 1828, having obtained letters of recommendation from the Duke of Montrose and Thomas Telford, a prominent British engineer, he departed for the Canadas.

Baird’s letters brought him quick employment. On 5 July he was received by the governor-in-chief, Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay], who the next day ordered him to proceed to the Rideau Canal. Eight days later, at Bytown (Ottawa), arrangements were made for him to replace John Mactaggart* as clerk of works on the canal. A demanding supervisor, Baird quickly impressed his superiors with his talents. During his four years on the Rideau he became interested in the problems of bridge building in the Canadas and devised a plan for a “suspension wooden bridge,” for which he received a patent in 1831. In September 1832, apparently with Lieutenant-Colonel John By’s support, he was commissioned by the provincial government to survey the mouth of the Trent River and design a bridge to span it. His professional status was recognized in Great Britain in February 1831, when he was admitted to the Institution of Civil Engineers, of which Thomas Telford was chairman.

In the spring of 1833 the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Sir John Colborne*, responding to local pressure to develop internal navigation in the Newcastle District, commissioned Baird to undertake a survey and prepare estimates for canals between the Bay of Quinte and Presqu’ile Bay and from the mouth of the Trent River to Rice Lake. In 1835, assisted by Frederick Preston Rubidge*, he prepared a report on the practicability of a canal between Rice Lake and Lake Simcoe. The report emphasized not only the local advantages of a line of navigation between lakes Ontario and Huron but also the commercial and military advantages that would be gained for the colony as a whole. In 1836 Baird was given the opportunity to carry out his plans when he was employed as superintending engineer by both the commissioners for the improvement of the Trent River and the commissioners for the inland waters of the Newcastle District.

Under Baird’s supervision, work along the waterway progressed slowly, hindered by the rebellion of 1837–38 and by the province’s financial difficulties in the late 1830s. Finally, in 1841 the government, on the recommendation of Hamilton Hartley Killaly*, concluded that the completion of the entire canal between Trent Port (Trenton) and Lake Simcoe was unwarranted. An expedient similar to one proposed by Baird in his 1835 report was adopted instead. Works that were well under way were to be completed and Scugog and Rice lakes, which formed parts of the canal route, connected to Lake Ontario by a road. Under the united province’s Board of Works, formed in 1841, Baird oversaw the implementation of this scheme. With the exception of a brief period in 1842, he was employed continuously on the Trent works until October 1843.

Like many engineers of the period, Baird was inclined to over-extend himself by undertaking a number of tasks at one time. In January 1835 he examined the feasibility of constructing a canal to join Lac Saint-Louis and Lac Saint-François on the St Lawrence River. The following year he was approached by William Hamilton Merritt* to become the engineer of the Welland Canal but he demanded a salary that Merritt considered excessive. When the House of Assembly passed an act in 1837 requiring that two practical engineers do a study of the route for an enlarged Welland Canal, Baird and Killaly were chosen. Jointly they prepared a report that was presented to the assembly in February 1838. As well, Baird was involved in the survey and construction of Windsor (Whitby) harbour, improvements to Cobourg harbour, the survey of a Cobourg–Peterborough railway, the construction of Presqu’ile Point lighthouse, and the preparation of a report for the Gananoque and Wiltsie Navigation Company [see John McDonald*]. For a brief period in 1840 he was engineer of the Chambly Canal but was dismissed in November of that year.

Early in 1840 Baird was requested by Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson to prepare a report outlining his views on water communications in Canada. He argued that the Welland and St Lawrence systems were of great importance to Canadian commerce. He felt that locks there should equal in size those of the Rideau Canal in order to accommodate large sailing vessels as well as the medium-sized steamers that made up most of the traffic on the Great Lakes. Baird saw a two-fold advantage in his system. Sailing-craft were “less subject to monopolies by wealthy Companies by whom alone Steamer transportation can be expected to be carried on.” Competition between sail and steam would reduce freight rates. At the same time, with passage possible for larger vessels, lake-craft would be able to reach the West Indies and return without breaking bulk.

Despite these views, Baird soon turned his attention to finding a means of modifying steam-vessels so that they could more easily navigate existing locks. He devised a scheme for a “sweeping paddle wheel,” for which he obtained an Upper Canada patent in 1842. Each of his two side-mounted paddle-wheels was narrower than normal, thus reducing the vessel’s width, and each had a deeper stroke, thereby imparting greater speed and stability. Baird’s proposal to have this design tested on a naval steamer had been resisted in 1841 by Williams Sandom*, the British captain commanding on the Great Lakes. However, his successor, William Newton Fowell*, was receptive and in 1845 the Admiralty authorized the alteration of the Mohawk at Penetanguishene to utilize Baird’s paddle-wheels. With them the vessel was able to come down through the Welland Canal and so “supervise the whole of the Lakes.”

With fewer opportunities for engineering work in the late 1830s and early 1840s, Baird became increasingly concerned about both recognition in the Canadas of British-born engineers and competition from Americans. When the commissioners of the Cornwall Canal explained that they had employed an American to supervise the works because there were “no Engineers in the Country known to them,” Baird wrote testily in 1840 or 1841 that he would not “yield an iota of Superiority to any Engineers from the United States.” He proceeded to draft an open letter to the Montreal Gazette showing that he was fully qualified to undertake the work.

During this period Baird ran up considerable debts, to George Strange Boulton* and John Redpath* among others, and seems to have alienated a number of people. H. H. Killaly continued to befriend him, offering advice to help him avoid mistakes, but even he was moved to warn Baird’s wife not to put money or property into his hands. When the Trent works was transferred in 1843 to district engineers, under the Board of Works, Baird was passed over for a junior person. Following his departure from the Newcastle District in October of that year, Baird was unable to obtain full-time employment for some time. In June 1845 he was re-employed by the board, possibly through Killaly’s influence, to lay out and superintend the construction of the Arthabaska Road, joining Quebec and Melbourne. He was also to undertake the improvement of the Kennebec Road, from Quebec to the Maine border. Baird completed the surveys by the end of the year and until the summer of 1848 supervised construction of the roads. During the following summer he was briefly employed with an American engineer examining the proposed route for a railway linking Montreal and Burlington, Vt. He was apparently unemployed at the time of his death in October 1849.

Baird’s most significant contribution lies in the development of early canal and road systems in Upper and Lower Canada. Associated most frequently with local works, he none the less had the opportunity to contribute to the development of major navigation systems such as the Rideau, Trent, and Welland canals. Until some time in the early 1840s he had access to those in office, who appear to have sought and respected his opinions about public works. Baird’s other, and perhaps greater, contribution is the volume of the historical record he left. Its completeness offers a rare opportunity to study early engineering in Canada.

AO, MS 393. Institution of Civil Engineers (London), Minute-book, no.242 (membership record of N. H. Baird, 8 Feb. 1831). PAC, RG 1, L3, 54: B17/183; RG 5, A1: 59532–33, 59542, 67405–8, 103137–54, 130725–27; RG 11, A2, 94, nos.449, 3344; 100; A3, 115: 175; RG 43, CII, 1, 2434. “Mortality schedules of Vermont, no.3: census of 1850,” comp. Carrie Hollister (typescript, Rutland, Vt., 1948; copy at Vt. Hist. Soc., Montpelier), 7. U.C., House of Assembly, App. to the journal, 1836, 1, no.12; Journal, app., 1833–34: 154–61. The valley of the Trent, ed. and intro. E. C. Guillet (Toronto, 1957). Montreal Witness, Weekly Review and Family Newspaper, 5 Nov. 1849. Patents of Canada . . . [1824–55] (2v., Toronto, 1860–65), 1: 389.

Cite This Article

John Witham, “BAIRD, NICOL HUGH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baird_nicol_hugh_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baird_nicol_hugh_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | John Witham |

| Title of Article: | BAIRD, NICOL HUGH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |

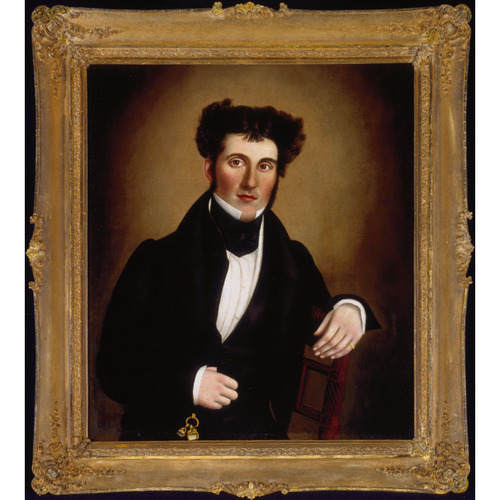

![Portrait de Nicol Hugh Baird (1796-1849) [huile sur toile, document iconographique]. Original title: Portrait de Nicol Hugh Baird (1796-1849) [huile sur toile, document iconographique].](/bioimages/w600.7777.jpg)