As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

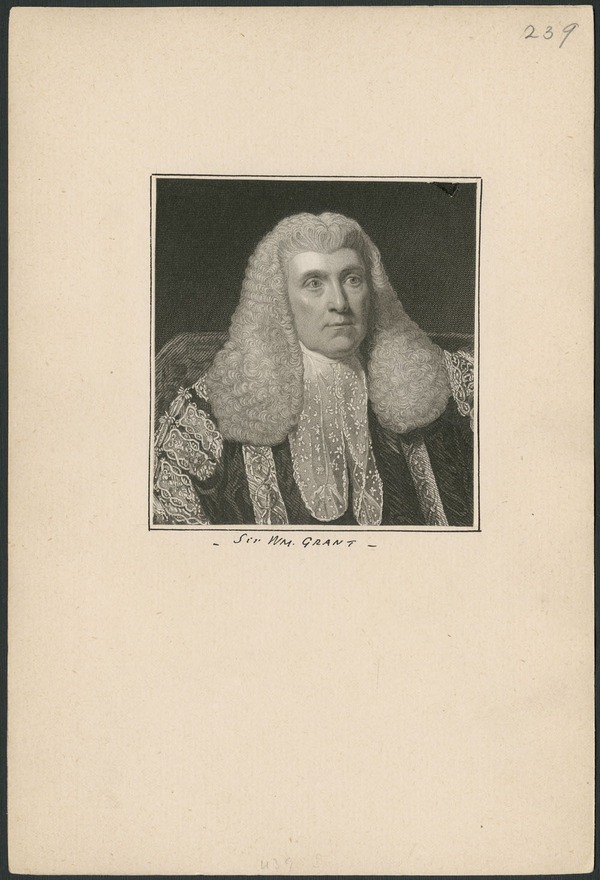

GRANT, Sir WILLIAM, lawyer, militia officer, and office holder; b. 13 Oct. 1752 in Elchies, Scotland, son of James Grant, a farmer and customs collector; d. unmarried 23 May 1832 in Dawlish, England.

William Grant studied first at Elgin, Scotland, and subsequently at King’s College in Aberdeen. Then he did Roman law for two years at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. Admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in London as a law student on 30 Jan. 1769, he was called to the bar on 3 Feb. 1774.

Grant arrived at Quebec in 1775. When the Americans invaded that year [see Benedict Arnold*; Richard Montgomery*], he participated in the defence of the town, taking command of a corps of volunteers. Following the departure for England in 1775 of the attorney general, Henry Kneller*, Grant was chosen to assume the post temporarily and on 10 May 1776 Governor Guy Carleton* appointed him to it officially. The right of appointment, however, rested with the crown. Consequently Carleton asked his lieutenant governor, Hector Theophilus Cramahé*, to write to Lord George Germain, the secretary of state for the American colonies, recommending Grant. In his letter of 18 Aug. 1776, Cramahé put forward Grant’s great qualities and his knowledge of the French language and law. In the mean time Germain had chosen James Monk for the office. When he learned this in May 1777, Carleton could not conceal his dissatisfaction, particularly since the rebuff over Grant had been preceded by that over judge John Fraser, and thus was the second case of the sort to come up in a short period. On 23 May he wrote to Germain emphasizing that he had “turned out of their Employments two men of Abilities and good Character.” Then he added: “I am at a loss to know, after the fate of these gentlemen, how I can even talk of rewarding those who have preserved their Loyalty without an Appearance of Mockery. Of this you may be assured that such things will occasion no small exultation among the King’s enemies.” Nevertheless, Grant’s office had been lost to Monk.

During his brief term as attorney general Grant had drawn up three ordinances to give the province its first regular judicial system since the Quebec Act: the ordinance of 25 Feb. 1777 establishing civil courts in the province, another adopted the same day establishing procedures in these courts, and a third, of 4 March, setting up criminal courts. In drawing up these measures Grant took inspiration from a plan prepared by Chief Justice William Hey* before he left for England in 1775. By their terms the province was divided into the districts of Quebec and of Montreal, as it had been prior to the Quebec Act.

The judicial structure for dealing with criminal cases was not greatly altered. The only change was to give the limited powers of bailiffs to militia captains. Justices of the peace had always had broad powers of first instance deriving much more from their commission than from an ordinance. The Court of King’s Bench remained a court of first instance, with full authority. There was again provision for convening assize courts.

By contrast, the judicial system for civil cases underwent major change. The Court of King’s Bench ceased to have jurisdiction in this field. The Court of Common Pleas in each district became the only one to exercise complete authority in all civil suits of first instance. The same laws were to be applied in all courts; these consolidated the regulations laid down by the Quebec Act and the ordinances of the governor and the Legislative Council. The bailiffs’ limited field of jurisdiction disappeared. There was no longer any provision for the appointment of judges to settle suits of minor importance. In respect of appeals the powers of the governor and the Legislative Council were widened. The decisions of the Court of Common Pleas of each district could be taken to the Court of Appeals, which was composed of the governor and the legislative councillors, in cases involving more than £10 sterling or “the taking or demanding any Duty payable to His Majesty, or to any Fee of Office or Annual Rents, or other such like Matter or Thing, where the Rights in future may be bound.” Finally, decisions from this court could be appealed to the Privy Council in London in cases where more than £500 sterling was in dispute or “where the Rights in future may be bound.” As for civil procedure, it was mixed, being partly French and partly English. In addition English rules of evidence were introduced in commercial matters.

On 25 Oct. 1778 Grant left Quebec and returned to Britain, where he was to have a remarkable career as a lawyer, politician, and judge. As legal counsel, he agreed in 1787 to undertake the defence in England of the judges of the Court of Common Pleas in the District of Quebec, who had been subjected to an investigation by Chief Justice William Smith* following charges brought against them by Monk.

In 1790 Grant was consulted by Prime Minister William Pitt about the reforms needed in the government of the province of Quebec, and he became a protégé of the famous politician. In June of that year he was elected to the House of Commons for the borough of Shaftesbury. The following year he took an energetic part in the discussion on the Constitutional Act. When he was called to serve as judge of the high court sessions at Carmarthen in 1793, he had to give up his seat in parliament. In February 1794 he was elected for the borough of Windsor, and that year he was appointed the queen’s solicitor general.

From June 1796 till September 1812 Grant represented the Scottish county of Banffshire. Two years after this term in the house began, he accepted the office of chief justice of the district of Chester. He was appointed solicitor general in the Pitt government on 18 July 1799 and retained the office until Pitt’s resignation in February 1801. In 1799 also he was knighted.

On 21 May 1801 Grant became a member of the Privy Council. Six days later he was appointed to the important office of master of the rolls, which he held until he retired on 23 Dec. 1817. He was elected rector of King’s College, Aberdeen, in 1809. Grant died on 23 May 1832 at Dawlish. His decisions had strongly influenced the development of equity in English law. Sir Samuel Romilly, the noted jurist, praised “his eminent qualities as a judge, his patience, his impartiality, his courtesy to the bar, his despatch, and the masterly style in which his judgments were pronounced.”

PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 12: 173; 13: 160, 180; 14: 264; 19: 266; RG 4, B8, 28: 56. Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1759–91 (Shortt and Doughty; 1918). Quebec, Legislative Council, Ordinances, 1777, c.1, c.2, c.5. Quebec Gazette, 29 Oct. 1778. F.-J. Audet et Fabre Surveyer, Les députés au premier parl. du Bas-Canada, 231. DNB. A. W. P. Buchanan, The bench and bar of Lower Canada down to 1850 (Montreal, 1925), 71, 73, 75. John Campbell, The lives of the chief justices of England, from the Norman conquest till the death of Lord Tenterden (5v., Long Island, N.Y, 1894–99), 4: 460. William Holdsworth, A history of English law, ed. A. L. Goodhart et al. (7th ed., 15v., London, 1956), 13: 278, 501, 578, 656–62. H. M. Neatby, The administration of justice under the Quebec Act (London and Minneapolis, Minn., [1937]), 31, 37–40, 259–60, 351; Quebec, 162–63. W. R. Riddell, The bar and the courts of the province of Upper Canada or Ontario (Toronto, 1928), 27. H. S. Smith, The parliaments of England from 1715 to 1847, ed. F. W. S. Craig (2nd ed., Chichester, Eng., 1973), 12, 91, 622–23.

Cite This Article

Jacques L’Heureux, “GRANT, Sir WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grant_william_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grant_william_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques L’Heureux |

| Title of Article: | GRANT, Sir WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |