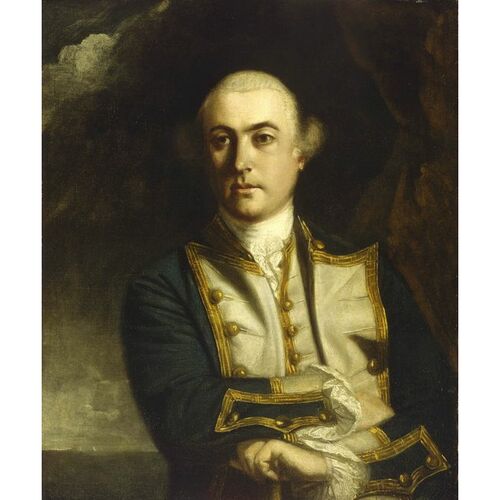

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BYRON, JOHN, naval officer and governor of Newfoundland; sometimes called Foul-weather Jack for the storms his ships so often endured; b. 8 Nov. 1723, second son of William Byron, 4th Baron Byron, and his third wife Frances Berkeley; m. 8 Sept. 1748 Sophia Trevannion, and they had two sons and seven daughters; d. 10 April 1786 in London, England.

According to contemporary accounts, John Byron entered the Royal Navy in 1731. Nine years later he sailed as a midshipman in the Wager (24 guns), one of Commodore George Anson’s squadron going to the Pacific. The Wager was wrecked on the southern coast of Chile, and after surviving this and other hardships Byron eventually found his way back to England in February 1745/46. By December he had been promoted post-captain and appointed to the Siren (24 guns), which he commanded until the end of the War of the Austrian Succession.

Byron commanded several ships during the Seven Years’ War; in 1760, in the Fame (74 guns), he was sent in command of a small squadron consisting of the Fame, Dorsetshire (70 guns), Achilles (60 guns), and Scarborough (22 guns) to Louisbourg, Cape Breton Island, to assist the garrison in demolishing the fortifications. He arrived on 24 May but on 19 June interrupted the work to go in search of a French convoy which was reported to be in the Restigouche River (N.B.) supplying an armed force on the Gaspé coast. Byron was separated from the rest of his squadron, which had been joined by the Repulse (32 guns), so that between 22 and 26 June the Fame sounded her way alone up an extremely narrow unmarked channel in the Baie des Chaleurs in search of the French vessels. Joined the following day by the rest of his ships, Byron then painstakingly worked his way into the mouth of the Restigouche, accompanied by the Repulse and the Scarborough. On the 28th the Fame destroyed a battery on the north shore which had been impeding the progress of the British ships, and on 8 July the two frigates came within range of the French force, which included the frigate Machault (32 guns) and two flutes. The Machault struck and later blew up, while the storeships were burnt. Byron’s men also burnt all the houses they could find ashore. This episode, sometimes called the battle of the Restigouche, was the last naval engagement of the Seven Years’ War in North America [see also François-Gabriel d’Angeac].

Byron returned to England in November, and in 1764 he hoisted a commodore’s broad pendant in the frigate Dolphin (24 guns) for a voyage to the Pacific in company with the sloop Tamar (16 guns). The expedition discovered several clusters of islands and returned to England in 1766 after having circumnavigated the world.

Three years later Byron was appointed governor of Newfoundland, going out in command of the Antelope (54 guns) in 1769 and the Panther (60 guns) in 1770 and 1771. He was governor at an interesting period in the island’s history, but his achievements have been overshadowed by those of his predecessor, Hugh Palliser. Byron did his best to satisfy both the Board of Trade and the inhabitants and cannot be said to have made any significant innovations of his own. Like Palliser, he received frequent complaints from both French and English about interference with each other’s fishery. Byron was, however, less severe on French vessels found fishing outside treaty limits, and his relations with d’Angeac, the governor of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, were smoother than those between Palliser and d’Angeac. Byron also turned his attention to the questions of customs and naval officers’ fees, the salmon fishery, and the seal fishery of the Îles de la Madeleine. His effectiveness as governor in 1771 was limited by his inability to visit the outports, since he had been instructed by the Admiralty to make his seamen available for the building of fortifications at St John’s. Byron was succeeded as governor in 1772 by Commodore Molyneux Shuldham.

In March 1775 Byron was promoted rear-admiral of the blue and by January 1778 had risen to the rank of vice-admiral of the blue. Four months later he was placed in command of a squadron fitting out for North America, and on 9 June he sailed, flying his flag in the Princess Royal (90 guns), in order to intercept a French fleet under the Comte d’Estaing. Byron reached New York alone on 18 August, his ships having been dispersed by storms, and then sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where the squadron was reunited on 26 September. Bad weather frustrated further attempts to find the enemy, and it was not until 6 July 1779 that Byron caught up with d’Estaing off Grenada in the West Indies, where his 21 ships fought a bold but indecisive action against 25 French vessels. He returned to England in October. In September 1780 he was promoted vice-admiral of the white, but he had no further employment before his death. His eldest son John, “a handsome profligate,” was the father of George Gordon, Lord Byron, the poet, and the sufferings of Don Juan in Byron’s poem were, according to the author, based on “those related in my grand-dad’s ‘Narrative.’”

A portrait of John Byron by Sir Joshua Reynolds hangs in the Painted Hall at Greenwich Naval College, London. Byron was author of: Byron’s journal of his circumnavigation, 1764–1766, ed. R. E. Gallagher (Cambridge, Eng., 1964); The narrative of the Honourable John Byron (commodore in a late expedition around the world), containing an account of the great distresses suffered by himself and his companions on the coasts of Patagonia from the year 1740 till their arrival in England, 1746 . . . (London and Dublin, 1768).

PRO, Adm. 1/482; 1/486, ff.165, 231–40; 1/1442; 1/1491; 51/3830; CO 194/28; 194/29, ff.28, 47–50; 194/30, ff.3, 9–12, 15, 31, 57–65; 195/9; 195/10, ff.1–105; 195/15; 195/18; 195/21; Prob. 11/1140, f.202. Knox, Hist. journal (Doughty), II, III. Charnock, Biographia navalis, V, 423ff. Colledge, Ships of Royal Navy, I. DNB. [A list of the ships Byron served in is available in the entry. w.a.b.d.] G.B., Adm., Commissioned sea officers. W. L. Clowes, The Royal Navy; a history from the earliest times to the present (7v., London, 1897–1903), III. John Creswell, British admirals of the eighteenth century; tactics in battle (London, 1972). [Creswell rehabilitates Byron’s reputation as a tactician in his analysis of the battle off Grenada, bringing in considerations which had been overlooked by Byron’s chief critics, A. T. Mahan and J. K. Laughton. w.a.b.d.] C. H. Little, The battle of the Restigouche: the last naval engagement between France and Britain for the possession of Canada (Halifax, 1962). A. T. Mahan, The influence of sea power upon history, 1660–1783 (Boston, 1890). G. J. Marcus, A naval history of England (2v., London, 1961–71), I, 439. Bernard Pothier and Judith Beattie, The battle of the Restigouche, 22 June–8 July, 1760 (Can., National Historic Sites Service, Manuscript report, no.19, [Ottawa], n.d.). [Consists of two reports, one by Beattie (1968) and the other by Pothier (1971).] Prowse, History of Nfld. W. H. Whiteley, “Governor Hugh Palliser and the Newfoundland and Labrador fishery, 1764–1768,” CHR, L (1969), 141–63; “James Cook and British policy in the Newfoundland fisheries, 1763–7,” CHR, LIV (1973), 245–72.

Cite This Article

W. A. B. Douglas, “BYRON, JOHN (Foul-weather Jack),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/byron_john_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/byron_john_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. A. B. Douglas |

| Title of Article: | BYRON, JOHN (Foul-weather Jack) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |