As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

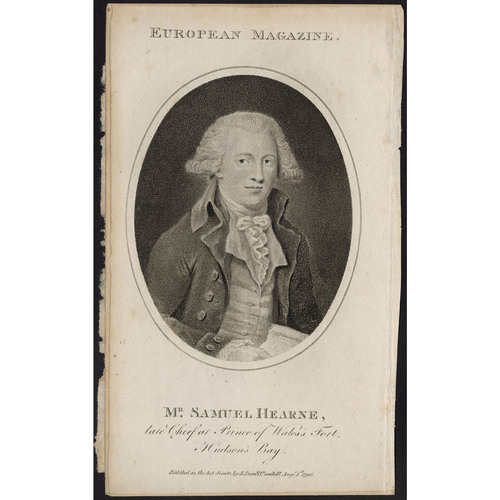

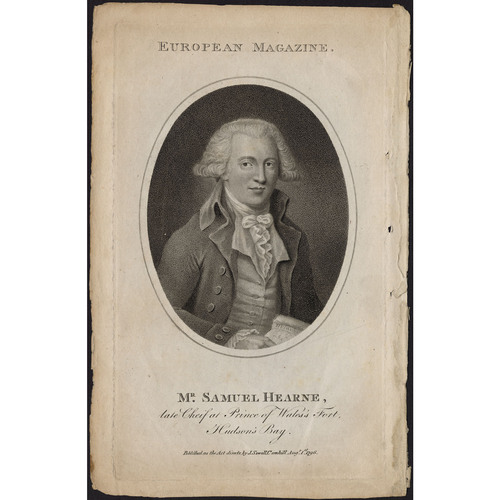

HEARNE, SAMUEL, explorer, fur-trader, author, and naturalist; b. 1745 in London, England, son of Samuel and Diana Hearne; d. November 1792 in London.

Samuel Hearne’s father, who had shown energy and imagination as managing engineer of the London Bridge Water Works, died in 1748. Mrs Hearne then took her son and daughter to Beaminster, in Dorset. After some elementary education, Hearne joined the Royal Navy in 1756 as a servant to Captain Samuel Hood. He saw considerable action during the Seven Years’ War, including the bombardment of Le Havre, France. He left the navy in 1763, and his activities during the next three years are unknown. In February 1766 he joined the Hudson’s Bay Company as a mate on the sloop Churchill, which was then engaged in the Inuit trade out of Prince of Wales’s Fort (Churchill, Man.). Two years later he became mate on the brigantine Charlotte and participated in the company’s short-lived black whale fishery.

In the mid 18th century the HBC was heavily criticized for not fulfilling its charter responsibilities to explore. The company’s enthusiasm for exploration had waned after the tragic ending in 1719 of James Knight*’s expedition, remains of which were discovered by Hearne on Marble Island (N.W.T.) in 1767. Probes by sea for a northwest passage out of Hudson Bay, such as that conducted by Christopher Middleton* in 1742, had run into dead ends. Nonetheless, an incentive for further exploration remained in the long reputed presence of pure copper in the remote northwestern interior. In 1762 Moses Norton sent two Indians, Idotliazee and another (probably Matonabbee), to explore to the northward of Churchill. On their return in 1767 they reported the existence of “a River whch Runs up between 3 Cooper mines . . . and is a very Plentifull Country of ye Best of furrs,” and they brought a sample of the ore. Norton went to England in 1768 and persuaded the company’s London committee to authorize the sending of a European to pin down the mines’ location and to report on the navigability of the adjacent river (Coppermine River, N.W.T.). The company hoped that the mines would prove large enough to provide “handy lumps” of copper to ballast its supply ships returning from the bay; at the very least, the overland journey would be a kind of propaganda tour to encourage distant tribes to trade at Churchill. Somewhat to his surprise, Hearne was “pitched on” as the proper person to head the expedition. He was young and fit and had a reputation for snowshoeing. He had improved his navigational skills by watching the astronomer William Wales, who had spent the 1768–69 season at Prince of Wales’s Fort.

Norton insisted on planning Hearne’s first two attempts to reach the Coppermine. Unfortunately, his choice of Indian guides was less than astute. The first, Chawchinahaw, was told to conduct Hearne to Matonabbee somewhere in the “Athapuscow Indians country” but abandoned him shortly after they started out on 6 Nov. 1769. The second attempt began on 23 Feb. 1770 with Conneequese, who claimed to have been near the Coppermine River. He got lost after months of arduous travel northwards into the bleak Dubawnt River country (N.W.T.), and he could not even prevent passing Indians from robbing Hearne and his two Home Guard Crees The accidental breaking of Hearne’s quadrant simply confirmed the futility of proceeding.

Upon returning to Prince of Wales’s Fort on 25 Nov. 1770, Hearne greatly provoked Norton by refusing to use any of his guides again. Norton did not, however, allow this animosity to “interfere with public business,” and he provided Hearne with all necessary supplies and accepted his choice of Matonabbee as guide. Matonabbee’s appointment was most auspicious. He had been to the Coppermine, had recently met and developed a liking for Hearne, and was devoted to the mission. More important, as a leading Indian he had great prestige among the Chipewyans and the Athabascan Crees and had developed as well a relatively organized pattern of movement between the trade posts on the coast and the interior. Hearne simply attached himself to Matonabbee’s “gang,” which included his six wives and from time to time picked up other Indians.

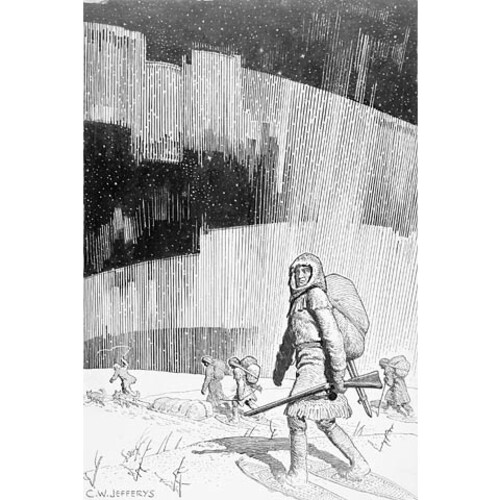

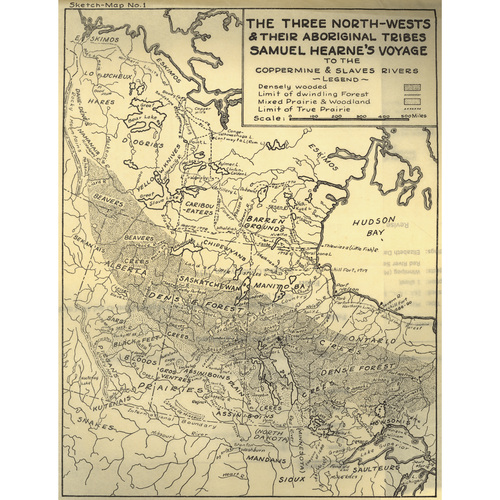

The third expedition left Prince of Wales’s Fort on 7 Dec. 1770. The hardships Hearne faced on this as well as the two previous expeditions can scarcely be exaggerated. Since the tiny canoes used by the Indians were suitable only for crossing rivers, Hearne and his companions had to make their way by foot across trackless wastes. Hearne himself was burdened by a 60-pound pack made awkward by a quadrant and its stand. Snowstorms hit viciously even in July and he frequently had no tent or dry clothes. On the barren lands it was “either all feasting, or all famine.” Although he became accustomed to eating caribou stomachs and raw musk-ox, he drew the line at lice and warbles; after long fasts eating caused him “the most oppressive pain.” Eventually he learned what the Indians already knew from experience – that travel was possible only by patiently following the seasonal movements of buffalo and caribou, their only source of food. Hearne’s success as an explorer was largely the result of his adaptation to their way of life and movement.

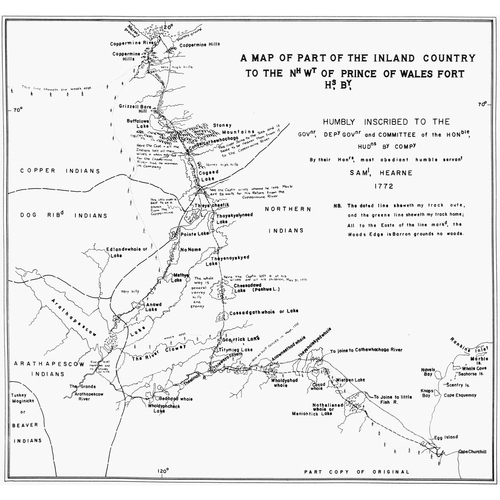

After travelling westward to Lake Theleweyaza-yeth (probably Alcantara Lake, N.W.T.), Hearne and his companions headed north and reached the Coppermine River on 14 July 1771. He quickly saw that shoals and falls made the river useless for navigation. Hearne had been ordered “to smoke your Calimut of Peace,” but when Matonabbee’s men came across a band of Inuit he was forced to take part in the preparations for their massacre. His protests were derided, and to avoid his companions’ contempt he had to arm himself. During the massacre he “stood neuter in the rear,” but an Inuit girl was speared so close to him “that it was with difficulty that I could disengage myself from her dying grasps.” He named the place Bloody Falls and could never “reflect on the transactions of that horrid day without shedding tears.” Continuing his survey of the river another eight miles, he came to the partially frozen Arctic Ocean on 17 July – the first European to reach it overland in North America. The Indians then took him 30 miles south to one of the copper mines. Hearne was totally disillusioned when an intensive search of the area yielded only one four-pound lump of copper. The Indians, anxious to get to Cogead (Contwoyto) and Point lakes, where their wives awaited them, doubled the pace of their return journey, causing Hearne to lose his toenails and suffer excruciating pain. In midwinter he became the first European to see and cross Great Slave Lake. The expedition arrived back at Prince of Wales’s Fort on 30 June 1772, in time to meet the supply ship from England.

The results of his 32 months of travel were, Hearne recognized, “not likely to prove of any material advantage to the Nation at large, or indeed to the Hudson’s Bay Company.” Nevertheless, his failure to find an east-west waterway crossing his northern route was important in casting doubt on its existence. Despite his careful attempt at calculation of the latitude at Congecathawhachaga (near Kathawachaga Lake, N.W.T.) on 1 July 1771, he placed the mouth of the Coppermine River 200 miles too far to the north, but the error reinforced his important conclusion that there was no northwest passage via Hudson Bay. It was on the basis of this judgement that Captain James Cook was told not to begin a serious search for a passage from the Pacific side until reaching 65°N latitude. The geographer Alexander Dalrymple nevertheless still believed in the existence of a northwest passage, and in pointing out some of Hearne’s exaggerations he discredited his standing as an explorer for years to come.

Following his travels Hearne served briefly as mate on the Charlotte but, despairing of the coastal trade, he requested “some Principal station in the land service.” Undoubtedly on the strength of his impressive journals, which reached the London committee at about the same time as Andrew Graham*’s persuasive memorandum urging the establishment of inland posts to meet Canadian competition, Hearne was chosen in 1773 to found the company’s first western inland post. Having learned to live off the land, he took minimal provisions for the eight Europeans and two Home Guard Crees who accompanied him. They went inland on 23 June 1774 as passengers in the canoes of the Indians who had come to trade at York Factory (Man.). Matthew Cocking and reinforcements failed to connect with Hearne’s party at Basquia (The Pas, Man.). After consulting some local chiefs, Hearne chose a strategic site on Pine Island Lake (Cumberland Lake, Sask.), 60 miles above Basquia. The site was linked to both the Saskatchewan River trade route and the Churchill system. There he directed the construction of Cumberland House, the oldest permanent settlement in the present province of Saskatchewan. Although instructed to keep “a distant civility” with the surrounding pedlars from Montreal, he appreciated their rescue of an HBC servant and returned the favour. He inspired his men to endure the first hard winter by restricting himself “to the very same allowance in every artical.” On 30 May 1775 he took out the first furs with the Indian canoes going down to York. On the return journey to Cumberland, he complained that the “villins of Indians that accompd me embezzeld at least 100 galns of the Brandy besides a Bag containing 43 lbs, of Brazil Tobaco, & 56 lbs of Ball.” Hearne advised the London committee that the company’s ability to extend its trade inland was hampered by its lack of canoes, and he suggested the development of a prototype of the later York boat. Eager to found more posts, he was instead appointed chief at Prince of Wales’s Fort, which he reached on 17 Jan. 1776.

Through circumstances largely beyond his control, Hearne’s years at Churchill were less productive than those he had spent inland. As the competition of the Canadian’ pedlars in the interior cut into the company’s profits, the London committee began to place an unrealistic emphasis on the white whale fishery of Hudson Bay as a source of supplies and on the northern coastal trade conducted by the ships of the bay posts. The whale fishery was not, however, productive and demanded as well the expense of highly paid whalers, which offset its usefulness. Hearne felt that the northern trade only intercepted the established trade at Churchill and allowed Indians to avoid paying their debts there, but his reluctance to press the trade earned for him the displeasure of the committee. The distant American revolution had an impact on his career as well. His fort, despite its 40-foot-thick stone walls, was scarcely defensible. It lacked drinking water, a ditch, and a military garrison, and its fortifications suffered from poor masonry, defective embrasures, and low elevation [see Ferdinand Jacobs]. On 8 Aug. 1782 Hearne and his complement of 38 civilians were confronted by a French force under the Comte de Lapérouse [Galaup] composed of three ships, including one of 74 guns, and 290 soldiers. As a veteran Hearne recognized hopeless odds and wisely surrendered without a shot. Most authorities who comment on his generally complacent attitude excuse it in this instance, as did the HBC at the time. Hearne and some of the other prisoners were allowed to sail back to England from Hudson Strait in a small sloop.

In September 1783 Hearne returned to build a modest wooden house (named Fort Churchill) five miles from the partially destroyed stone fort and on the exact site of the original post at Churchill. He found that the trade situation had deteriorated markedly. The Indian population had been decimated by smallpox and starvation due to the lack of normal hunting supplies of powder and shot. Matonabbee had committed suicide on learning of the fort’s capture, and the rest of Churchill’s leading Indians had moved to other posts. The competition of the Canadians, who by now had penetrated the homeland of the Chipewyans, was more intense than ever. Hearne grew sensitive about criticism of his handling of the northern coastal trade, the whale fisheries, and the smuggling activities of the company’s Orkney servants. He bitterly asserted to the London committee that he had “served you too Scrupulous and too Faithfully to become a Respectable character in your Service.” His health began to fail and he delivered up command at Churchill on 16 Aug. 1787.

During his retirement in London Hearne was mollified by the attentions of scientists and HBC directors. In the last decade of his life he used his experiences on the barrens, on the northern coast, and in the interior to help naturalists like Thomas Pennant in their researches. He also worked on the manuscript of what was to become A journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort, in Hudson’s Bay, to the northern ocean . . . in the years 1769, 1770, 1771, & 1772, the book which would establish his claim to fame. His original travel journals and maps of 1769–72 had not been intended for the public, but interest in the geography and life of the largely unexplored interior had led to their being lent by the company to the Admiralty and to scientists. In the years after his journey he had continued to compile material, and the Comte de Lapérouse, when he read the manuscript following his capture of Hearne, had urged its publication. In this opinion he was joined in England by Dr John Douglas, the editor of Cook’s journals, and William Wales.

Hearne’s Journey was published in London three years after he died. Before his death he had added to the manuscript two chapters on the Chipewyans and the animals of the northern regions and had inserted into his narrative, at appropriate places, descriptions of hunting methods, the treatment of women, Inuit artifacts, and the habits of beaver, musk-ox, and wood bison. His anthropological generalizations are backed by vivid accounts of actual individuals and events, and his portrait of the Chipewyans is one of the best of any tribe in the early contact phase. At pains to refute critics of the HBC’s inactivity in exploration, Hearne is still sufficiently philosophic to wonder if the Indians of the interior really benefited from the fur trade. The book, directed at the general public rather than at specialists, is written in a plain, unadorned style. It went through two English editions and by 1799 had been translated into German, Dutch, and French.

Hearne the fur-trader served his company well by land and by sea in a variety of responsibilities. The skill in observation and desire for realism revealed in his book mark him as a significant early naturalist. As an explorer and writer, he represents an interesting combination of physical endurance and intellectual curiosity.

[Samuel Hearne’s A journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort, in Hudson’s Bay, to the northern ocean . . . in the years 1769, 1770, 1771 & 1772 (London, 1795) was reprinted in Ireland (Dublin, 1796) and the United States (Philadelphia, 1802) and was translated into German (Berlin, 1797), Dutch (2v., The Hague, 1798), Swedish (Stockholm, 1798), French (2v., Paris, 1799), and Danish (Copenhagen, 1802). Two modern editions have been published, one edited by Joseph Burr Tyrrell* (Toronto, 1911; repr. New York, 1968) and the other by R. G. Glover (Toronto, 1958). Thanks to the work of these two men, in particular that of Glover, Hearne’s reputation is now secure. c.s.m.]

HBC Arch. A.11/14, ff.78, 81, 174; 11/15, ff.47, 80, 112; B.42/a/103, 14 Sept. 1783, 16 Aug. 1787; B.42/b/22, letter from Hearne, 21 Jan. 1776. Journals of Hearne and Turnor (Tyrrell). “Some account of the late Mr. Samuel Hearne,” European Magazine and London Rev. (London), XXXI (1797), 371–72. [David Thompson], David Thompson’s narrative, 1784–1812, ed. R. [G.] Glover (new ed., Toronto, 1962). George Back, Narrative of the Arctic land expedition to the mouth of the Great Fish River, and along the shores of the Arctic Ocean, in the years 1833, 1834, and 1835 (London, 1836), 144–55. J. C. Beaglehole, The life of Captain James Cook (Stanford, Calif., 1974). Morton, History of Canadian west. Rich, History of HBC, II. Gordon Speck, Samuel Hearne and the northwest passage (Caldwell, Idaho, 1963). G. H. Blanchet, “Thelewey-aza-yeth,” Beaver, outfit 280 (Sept. 1949), 8–11. R. [G.] Glover, “Cumberland House,” Beaver, outfit 282 (Dec. 1951), 4–7; “The difficulties of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s penetration of the west,” CHR, XXIX (1948), 240–54; “Hudson Bay to the Orient,” Beaver, outfit 281 (Dec. 1950), 47–51; “La Pérouse on Hudson Bay,” Beaver, outfit 281 (March 1951), 42–46; “A note on John Richardson’s ‘Digression concerning Hearne’s route,’” CHR, XXXI (1951), 252–63; “Sidelights on S1 Hearne,” Beaver, outfit 277 (March 1947), 10–14; “The witness of David Thompson,” CHR, XXXI (1950), 25–38. Glyndwr Williams, “The Hudson’s Bay Company and its critics in the eighteenth century,” Royal Hist. Soc., Trans. (London), 5th ser., XX (1970), 149–71. J. T. Wilson, “New light on Hearne,” Beaver, outfit 280 (June 1949), 14–18.

Cite This Article

C. S. Mackinnon, “HEARNE, SAMUEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hearne_samuel_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hearne_samuel_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. S. Mackinnon |

| Title of Article: | HEARNE, SAMUEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |