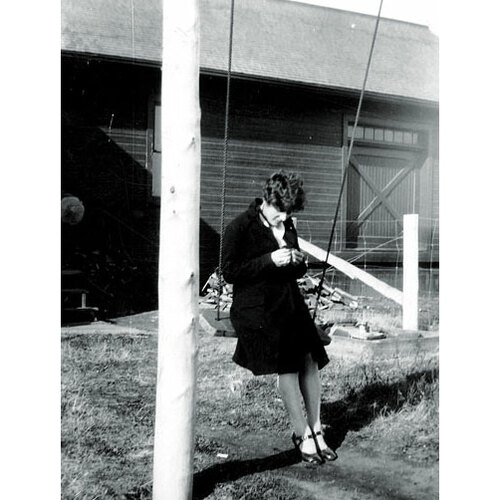

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

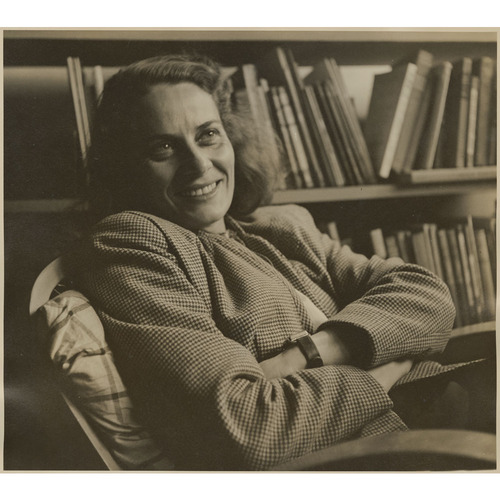

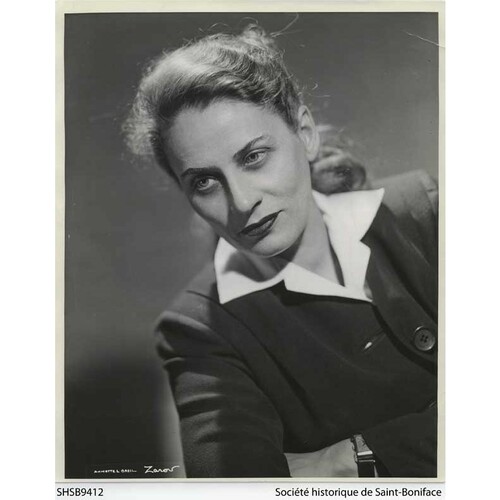

ROY, GABRIELLE (baptized Marie-Rose-Emma-Gabrielle) (Carbotte), novelist; b. 22 March 1909 in St Boniface (Winnipeg), daughter of Léon Roy and Mélina Landry; m. 30 Aug. 1947 Dr Marcel Carbotte (d. 8 July 1989) in St Vital, Man.; they had no children; d. 13 July 1983 at Quebec.

The first part of Gabrielle Roy’s life, which would provide her with a rich source of unforgettable memories and images as a novelist, was spent in Manitoba, to which her parents, both natives of the province of Quebec, had come at the end of the 19th century. Léon Roy had acquired a homestead in the so-called Pembina Mountain district in 1883. In 1886 he married 19-year-old Mélina Landry; the Landrys, who were originally from the Joliette region, had settled in the west a few years earlier. Soon after their marriage, Léon went into business, and he became increasingly active in the Liberal Party, an involvement that got him into trouble within his community. When Wilfrid Laurier* finally came to power in Ottawa in June 1896, Roy was hired as a government agent to welcome newly arrived settlers at Immigration Hall in Winnipeg and help them get established on the lands made available by the Department of the Interior. In 1897 he and his wife therefore moved to St Boniface, near Winnipeg, a town with a largely francophone, Catholic population that was the centre of French Canadian life in western Canada. When they settled in St Boniface, the Roys had five children: Joseph (b. 1887), Anna (b. 1888), Agnès (b. 1891), who would die of meningitis when she was 14, Adèle (b. 1893), and Clémence (b. 1895). Four others soon followed: Bernadette (b. 1897), Rodolphe (b. 1899), Germain (b. 1902), and Marie-Agnès (b. 1906), who died four years later, shortly after Léon Roy had a fine large house built for his family on Rue Deschambault in a new section of St Boniface.

Gabrielle Roy, born in this house and baptized in the cathedral at St Boniface, was thus the youngest of Léon and Mélina’s family. As there were a number of years between her and her brother Germain and the older children had already left home, she had a rather solitary childhood, with an ageing father whose work with the settlers often took him far away from his family, and a mother who coddled her as if she were an only daughter, especially since “Little Miss Misery” – as she was nicknamed – was never in robust health. While not wealthy, the Roys were relatively well-off, although their circumstances were somewhat compromised when Léon lost his job and his government salary in 1915. But even then, the family did not experience real poverty, since Roy managed to earn a decent living through various minor jobs and business deals. It was also in 1915 that Gabrielle began her schooling. She enrolled in the Académie Saint-Joseph, which was run by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary and was close to her home. In the 12 years she spent there, she officially was given an anglophone education, in accordance with the laws passed by the provincial parliament in the spring of 1916 under which English became the sole language of instruction in Manitoba public schools. Gabrielle Roy was thus introduced to the major authors in the British literary tradition, but the sisters also found ample time for instruction in the French language and the Catholic faith. Initially a rather poor student, she quickly became one of the school’s brightest pupils, distinguishing herself in composition and elocution, and winning medals and other school prizes every year, awarded, in particular, by the Association d’Éducation des Canadiens Français du Manitoba.

Once she had her grade 12 diploma, like many other gifted young women of the time Roy decided to become a teacher, a career that was both honourable and well paid. In September 1928, a couple of months before her father’s death, she enrolled in a one-year course at the Provincial Normal School in Winnipeg. The following spring, even before obtaining the teacher’s certificate that she was awarded on 27 June 1929, she went to work for a few weeks as a supply teacher in Marchand, a remote village in eastern Manitoba. But her first real appointment was to a rural school in Cardinal, a village in the region where her parents had been married and where her Landry uncles and aunts still lived. She taught there for the 1929–30 school year. In the fall of 1930 she was hired by the St Boniface School Board to teach at the Institut Collégial Provencher, a school for boys run by the Marianists, who gave her one of the first-year classes. She taught solely in English and would stay there for seven years.

Aside from the double advantage of living economically at home with her mother and getting a regular salary – roughly $100 a month, a sizeable sum during the Depression – the years Roy spent teaching there gave her the chance to enjoy the many social and cultural activities available in an urban setting, and the leisure to devote herself to pursuits that increasingly meant the most to her and that fuelled her most intense ambitions: writing and, above all, the theatre. An indefatigable reader, she managed to get a number of pieces, both in French and in English, published in local and national periodicals. But her real passion at this time was the stage, to which she was drawn by her talent, her beauty, and her desire for a cultured, sophisticated life, and to which she directed most of her energies. She took acting lessons, toured with groups of actors who gave performances in small francophone communities throughout Manitoba, and was heavily involved in the Cercle Molière, an amateur troupe directed by Arthur and Pauline Boutal [Le Goff*], who gave her parts in some of their annual productions. Two of these took her, in 1934 and again in 1936, to the Dominion Drama Festival in Ottawa, at which the actors from St Boniface won some awards. At the same time, Gabrielle, who took her acting very seriously, had roles in two English-language plays at the Winnipeg Little Theatre, where her performances were also favourably received by both the public and the critics. While not particularly outstanding, these successes strengthened her love of the theatre and convinced her she might have a career as an actress that would enable her to escape from her small-town environment and, with talking pictures being all the rage and radio broadcasting growing apace, would provide an ideal point of departure on the road to personal fulfilment and fame.

It did not take long for Gabrielle Roy to make up her mind: she would go to Europe to perfect her art. Even though it would mean depriving her elderly mother of the moral and financial support she badly needed, the young teacher began putting money aside for her trip. Having sought and obtained a leave of absence from the St Boniface School Board, in 1937 she took a summer teaching job in the Waterhen region, a remote community 500 kilometres north of Winnipeg, in order to augment her savings. No sooner was she back than it was time to say goodbye to her friends and set out on her voyage of discovery to the “old countries.” Roy was 28.

Her stay in Europe lasted almost two years, from the fall of 1937 to the spring of 1939. After a couple of weeks in Paris, where she found it difficult to fit in, she settled in London, where several of her Manitoban friends were already living. She enrolled in the famous Guildhall School of Music and Drama, visited museums, took trips to the English countryside, and mixed with other students from various Commonwealth countries.

Apart from the new freedom (particularly in religious matters) that Gabrielle found by living away from home, far removed from her native setting, her stay in England was marked by two notable events. First, she met a young Canadian of Ukrainian origin with whom she had her first real experience of passion. Their relationship did not last, however, for psychological reasons – Gabrielle was frightened by the physical and emotional dependence involved, which in her view ran counter to her desire for personal fulfilment. Perhaps there were ideological ones too, since the Stephen in question belonged to a network of Ukrainian nationalists engaged in a struggle against Joseph Stalin’s Union of Soviet Socialist Republics that made it necessary for him to be away frequently and, in the context of the period, rendered him an “objective” ally of the Nazis. Gabrielle’s sympathies, formed in the Manitoba of the 1930s, were rather with social-democratic and liberal ideals. She also reached a turning point in her career, a choice that would shape the rest of her life. In the summer of 1938, having resigned herself to the fact that she had neither the talent nor the voice to become an actress, Roy – as she would relate in her autobiography – discovered her true vocation. Staying in the little town of Upshire, in suburban London, at the home of her new friend Esther Perfect, who cared for her every need, she settled down seriously to write, and to write in French, which henceforth would be the sole language of her literary career. Initially, she produced only brief, inconsequential texts, short stories that she filed away and accounts based on her European experiences, some of which were published in a St Boniface newspaper. However, the fact that three of her articles were accepted by a well-known Parisian magazine convinced her that she had made the right choice and that her talent was real. She knew then that she would be a writer and she would never deviate from her path.

But war was approaching and it was necessary to leave Europe. Before doing so, Roy decided to spend a few months in the south of France, where the beauty of the landscapes overwhelmed her. She stopped briefly in Prats-de-Mollo, a village in the Pyrénées-Orientales, which at that time was full of Republican refugees from the Spanish Civil War. Finally, after returning to England, she sailed for her native land in April 1939.

Once back in Canada, and despite letters from her mother urging her to go home and resume her teaching position at the Institut Collégial Provencher, Roy elected to stay in Montreal, where nobody knew her, and try her luck as a writer. Thus began six years of constant hard work, undertaken with a view to perfecting her art, finding her own voice, and making a name for herself.

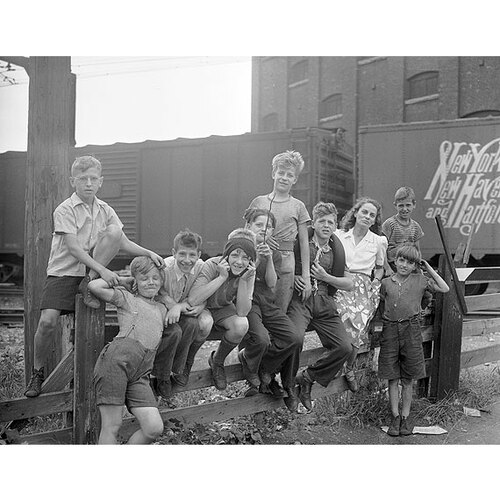

The timing was propitious, since Montreal was then experiencing an exciting time of change; conditions brought about by World War II and the advent of Adélard Godbout*’s Liberal Party to power combined to produce a lively climate receptive to new ideas and lifestyles, along with a rapid expansion of the press and the publishing industry. Thus it was as a freelance journalist and author of short-stories that Gabrielle Roy made her debut as a writer. Living in small rented rooms, mixing unobtrusively with artists and journalists located downtown, getting bit parts in radio dramas, she endeavoured to place her articles in various periodicals, to both earn her keep and have time for engaging in a more ambitious project. Having got a regular column on the women’s page of the Montreal weekly Le Jour, of which Jean-Charles Harvey* was the editor, she published short stories in La Revue moderne, a Montreal magazine whose literary editor, Henri Girard, became her patron (and maybe her lover). But it was above all as a reporter that Roy began to be noticed, when the Montreal periodical Le Bulletin des agriculteurs, having published a few of her pieces, commissioned her to write major series of articles that were spread over several issues and drew an increasingly wide audience. Four series based on documentary research but especially on personal observation appeared in this journal between 1941 and 1945: “Tout Montréal” (1941, four articles), a striking portrait of life in that city in its most varied and contemporary aspects; “Ici l’Abitibi” (1941–42, seven articles), in which the journalist accompanied a group of Madelinots who had resettled in the Abitibi region of northwestern Quebec; “Peuples du Canada” (1942–43, seven articles), a series of sketches of small communities she visited during a trip to western Canada, when she saw her mother for the last time; and finally “Horizons du Québec” (1944–45, fifteen articles), depicting the social and economic life of various regions of the province.

Roy’s contributions to Le Bulletin des agriculteurs allowed her to indulge in her love of travel and brought her the financial security to live more comfortably – sometimes at the Ford Hotel in Montreal, sometimes in Rawdon, in the house of a lady who took her in as a boarder. They also gave her time to work on a novel she had begun by 1941 or 1942, and a first version of it was completed in the summer of 1943 in the Gaspé, where she usually spent her holidays. Its title was Bonheur d’occasion. Set in the Saint-Henri district of Montreal during the winter and spring of 1940, the plot focuses on the story of a French Canadian family, the Lacasses, and especially on the mother, Rose-Anna, and her daughter Florentine. More broadly, the novel paints a striking picture of working-class life, as the people in Saint-Henri struggle against unemployment, poverty, and rootlessness; ironically, it is the war that offers them a chance to escape.

Published in June 1945 by the Société des Éditions Pascal, Bonheur d’occasion was enthusiastically received by both the general public and the Montreal and Toronto critics, who praised the novel’s realism and the quality of her writing as heralding a renewal of Canadian literature. But very quickly, its success spread much further. The English translation, brought out in New York in 1947 under the title The tin flute, was selected as book-of-the-month by the Literary Guild – an American book club – in May that year, with a print run of 700,000. Then a Hollywood company bought the cinema rights for $75,000 (but the script was never turned into a film, and years later the rights were acquired by a Canadian producer whose movie did not come out until 1983). Republished in France by Flammarion in the autumn of 1947, Bonheur d’occasion became the first Canadian novel to win a major prize on the Parisian literary scene when it was awarded the Prix Femina, and as a result would be translated into ten other languages in years to come. For Gabrielle Roy, these events constituted a far greater reward than she could ever have imagined for her years of effort to produce a work of quality and earn a place in the literary world. Above all, the success of Bonheur d’occasion completely transformed her life. Once an obscure journalist working for a farm magazine, she had become, overnight, a celebrity, showered with honours and money, hounded by interviewers, admired by thousands of readers, and hailed by the critics as a novelist of the first rank.

Though this success pleased her, she found all the fuss that came with it quite overwhelming. To get some rest, she therefore returned to Manitoba in May 1947 and stayed for some time with her sisters. While there she met Marcel Carbotte, a young physician for whom she felt a degree of affection and trust that few other men had inspired in her. They were married three months later and decided to spend several years in France, where he would train to become a specialist in gynaecology and she would devote herself solely to her writing. En route, they stopped off in Montreal, where Gabrielle gave her induction speech at the Royal Society of Canada, whose French section had just made her a member.

After reaching Paris early in the fall of 1947, they stayed first at the Hôtel Trianon Palace, and then at the Hôtel Lutetia, before settling down, the following autumn, in a middle-class boarding house in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Initially the Carbottes led a fairly active social life, enjoying excursions, outings with friends, in particular Jeanne Lapointe, Cécile Chabot, and Judith Jasmin*, and all kinds of parties. It was at one of these evening receptions that Roy met the Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (whose thinking would influence her profoundly and help persuade her at the time of the second Vatican Council some 15 years later to return to the Catholic faith). Then life resumed its normal course, and the novelist – who was often on her own, far away from Paris – began work on her second book, which gave her much difficulty. At first, she tried to write something fairly similar to Bonheur d’occasion, but she soon abandoned the effort. Then, one day when she was visiting Chartres, the landscapes and the ambience of her summer in the Waterhen district in 1937 came back to her. The three stories thus inspired constituted her next book, La Petite Poule d’Eau, which was published in Montreal in 1950 and had a rather cool reception. Toronto critics were enthusiastic, hailing the work as a masterful illustration of Canadian culture. (Its publication happened to coincide with the royal commission on national development in the arts, letters and sciences, or Massey-Lévesque commission.)

On their return to Canada on 15 Sept. 1950, Gabrielle Roy and her husband settled initially in the Montreal region at LaSalle, beside the St Lawrence. However, Gabrielle continued to seek refuge regularly in secluded places in order to write, notably in the Gaspé. Then, since Marcel Carbotte could not find an interesting position in the Montreal area and was offered one at the Hôpital du Saint-Sacrement in Quebec City, they moved to the old capital in 1952. It was there, in an apartment in the Château Saint-Louis on the Grande Allée, that she would for the most part live out the rest of her days.

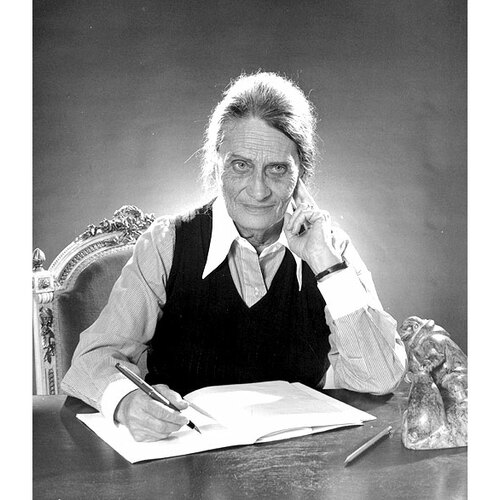

When she moved to Quebec City, Roy was only 43; yet it could be said that the essential part of her biography was over, in the sense that no major event would change the course of her life in any striking or significant way. Of course, she continued to travel a great deal, with trips to France (1955, 1963, 1966, 1973–74), Louisiana (which she visited in 1957 with her friend the painter René Richard and his wife), Arizona (1964, 1970–71), Florida (1967–68, 1968–69, 1978–79), Saskatchewan (1955), and, above all, Manitoba, since, after her sister Bernadette died in 1970, she was frequently called back to her native province to care for her other sister, Clémence, who could not look after herself. But these were uneventful journeys, undertaken solely to escape the rigours of winter or maintain family ties. The rest of her time was divided between the apartment in the Château Saint-Louis and a little house she had acquired in 1957 in the Charlevoix region, at Petite-Rivière-Saint-François, where she spent every summer, enjoying the mountain and the river, and writing. Of course she had many friends and correspondents (including Jean-Paul Lemieux and his wife, Adrienne Choquette*, Madeleine Bergeron, and her translator, Joyce Marshall); but these were strictly private, untroubled relationships. Certainly, she took an interest in contemporary social and political developments in the province of Quebec. She was delighted to witness the Quiet Revolution, educational reforms, and the emancipation of women, but was deeply disturbed by the rise of the sovereignist movement, especially during the 1970 October Crisis and on the eve of the referendum of 20 May 1980. On the other hand, she was sceptical about political engagement on the part of writers, and took care not to intervene in public debates except on one occasion, during the visit of French president Charles de Gaulle, whose speech she condemned in the press. A similar discretion marked Roy’s relations with the literary world. She kept up with new books as they appeared, read the reviews of her own work, and corresponded with fellow writers and her readers, but she avoided social gatherings, refused most requests for interviews, and never made public appearances. In short, her daily concerns and worries were of a strictly domestic and private nature, and she conducted her life on a single principle – to preserve her health and serenity so she could be free to focus on the only thing that mattered to her: the books to be written, the stories and the creatures of her imagination. All in all, there was something monastic about her existence; she was a woman determined to keep apart from the world, whose life was completely bound up with her endeavour to produce a carefully crafted body of work.

Taken as a whole, this oeuvre is one of the finest in Canadian and Quebec literature. Written in a fluid, spare style, it is distinguished by lively narration and a keen sense of observation, and approaches the world and people with clear sight and compassion. A substantial achievement built up gradually over the years, owing little to changing literary fashions, Roy’s work is one of the most original in Canada, as varied as it is cohesive. After La Petite Poule d’Eau, she returned to a novel with a Montreal setting that she had begun and then abandoned during her second stay in France, finally settling on the definitive form of what, after much effort, became Alexandre Chenevert; the story of a bank clerk torn between his personal troubles and the fate of humanity, it came out in Montreal in 1954. Then she took up the threads of her Manitoban past once more in 1955 and published Rue Deschambault (first in Paris and then in Montreal). Its central character, Christine, in some ways a fictional alter ego of Roy herself, would reappear in 1966 in a similar work brought out in Montreal, La route d’Altamont. Meanwhile, in 1961, La montagne secrète, a novel describing the adventures and the inner maturing of an artist, Pierre Cadorai, which was based loosely on the life of the painter René Richard, was also published there. Then she returned to social realism in La rivière sans repos (published in Montreal in 1970), a work set in Ungava illustrating the conflicts experienced by the Inuit, torn between their loyalty to traditional ways and the new ideas which modern progress brings. Two years later, Cet été qui chantait paid a moving tribute to the landscapes and people of Charlevoix, where she spent half the year; it was quickly followed in 1975 by Un jardin au bout du monde, a collection of four short stories set in the Canadian west, in which the characters are immigrants. The last two works were brought out in Quebec City and Montreal respectively.

In her final works, as in the last years of her life, Gabrielle Roy focused on themes of remembrance. Ces enfants de ma vie (Montréal, 1977) drawn on the years she spent teaching in Cardinal and St Boniface. Then Fragiles lumières de la terre (Montréal, 1978) gathered together a number of reportages and essays published in various places between 1942 and 1970. The culmination of this autobiographical strain was La détresse et l’enchantement, which Roy began to write around 1976. Knowing she had not long to live, she undertook in this final work to tell the story of her whole life, concentrating not so much on recounting historical facts as on recreating her inner feelings and thoughts over time. By evoking the people and events that had influenced her, with the sorrows, joys, and dreams she had known, she portrays herself both as she was and as she wanted to be, as if the work was to be a summation of her life and a preparation for leaving it. The work envisaged was to be in four parts, covering all her years, but she had time to write only the first two parts and the beginning of the third, dealing with the period from her Manitoban childhood until the composition of Bonheur d’occasion. It was published posthumously in Montreal in two volumes, La détresse et l’enchantement in 1984 and Le temps qui m’a manqué in 1997.

Gabrielle Roy died on 13 July 1983 at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec City after a heart attack, having made a will leaving her estate to her husband (who would die six years later) and various children’s aid organizations. Her ashes were laid to rest in what is now the Parc Commémoratif la Souvenance in Sainte-Foy, near Quebec City. Although there were periods when her work was relatively out of fashion (notably in the 1960s and the early 1970s), Roy’s literary reputation has remained constant ever since the publication of Bonheur d’occasion, making her one of Canada’s and Quebec’s most highly respected, widely read, and studied authors, both in Canada and elsewhere. A three-time winner of the Governor General’s Award (in 1947, 1957, and 1978), she received, among other distinctions bestowed for her work as a whole, the Prix Duvernay of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal (1956), the Prix David of the Quebec government (1971), the Molson Prize of the Canada Council for the Arts (1978), and a diplôme d’honneur from the Canadian Conference of the Arts (1980). She was made a doctor honoris causa of the Université Laval in 1968 and a companion of the Order of Canada in 1967.

For additional information about Gabrielle Roy, her autobiographical writings are useful, including certain parts of Fragiles lumières de la terre and particularly Roy’s posthumous works, La détresse et l’enchantement, Le temps qui m’a manqué, and Le pays de “Bonheur d’occasion” et autres récits autobiographiques épars et inédits, François Ricard et al., édit. (Montréal, 2000). Also worth consulting are five volumes of Roy’s correspondence: Ma chère petite sœur: lettres à Bernadette, 1943–1970, François Ricard et al., édit. (1re éd., Montréal, 1988; 2e éd., 1999); Mon cher grand fou -- lettres à Marcel Carbotte, 1947–1979, Sophie Marcotte, édit. (Montréal, 2001); Intimate strangers: the Gabrielle Roy-Margaret Laurence correspondence, ed. P. G. Socken (Winnipeg, forthcoming); In translation: the Gabrielle Roy–Joyce Marshall correspondence, ed. Jane Everett (Toronto, forthcoming); and Lettres à ses amies, Ariane Léger et al., édit. (Montréal, forthcoming). A complete and detailed biography, François Ricard, Gabrielle Roy, une vie: biographie (2e éd., Montréal, 2000), contains a chronological bibliography of all of Roy’s works, as well as an inventory of the archives that hold documents pertaining to her, the most important being the collection made up of LMS-0082 (Gabrielle Roy fonds) and LMS-0173 (Gabrielle Roy and Marcel Carbotte fonds) in Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa).

Among the bibliographies of critical writings devoted to both the works and the person of Gabrielle Roy, attention should be drawn to those of Marc Gagné, in Visages de Gabrielle Roy, l’œuvre et l’écrivain (Montréal, 1973), of François Ricard, in Introduction à l’œuvre de Gabrielle Roy (1945–1975) (2e éd., Québec, 2001), of P. [G.] Socken, “Gabrielle Roy: an annotated bibliography,” in The annotated bibliography of Canada’s major authors, ed. Robert Lecker and Jack David (8v. to date, Downsview [North York], Ont., 1979-?), 1: 213–63, and of Lori Saint-Martin, Lectures contemporaines de Gabrielle Roy: bibliographie analytique des études critiques, 1978–1997 (Montréal, 1998). Also worth consulting is the website of the Groupe de Recherche sur Gabrielle Roy, at the Département de langue et littérature françaises of McGill University, at the following address: ww2.mcgill.ca/gabrielle_roy.

Not only Bonheur d’occasion, but almost all of Roy’s works have been translated into English; these are the titles, in chronological order: Where nests the water hen [translation of La Petite Poule d’Eau], trans. H. L. Binsse (Toronto and New York, 1951); The cashier [translation of Alexandre Chenevert], trans. H. [L.] Binsse (Toronto and New York, 1955); Street of riches [translation of Rue Deschambault], trans. H. [L.] Binsse (Toronto and New York, 1957); The hidden mountain [translation of La montagne secrète], trans. H. [L.] Binsse (Toronto and New York, 1962); The road past Altamont [translation of La route d’Altamont], trans. Joyce Marshall (Toronto and New York, 1966); Windflower [translation of La rivière sans repos], trans. Joyce Marshall (Toronto, 1970); Enchanted summer [translation of Cet été qui chantait], trans. Joyce Marshall (Toronto, 1976); Garden in the wind [translation of Un jardin au bout du monde], trans. Alan Brown (Toronto, 1977); Children of my heart [translation of Ces enfants de ma vie], trans. Alan Brown (Toronto, 1979); The fragile lights of earth [translation of Fragiles lumières de la terre], trans. Alan Brown (Toronto, 1982); and Enchantment and sorrow [translation of La détresse et l’enchantement], trans. Patricia Claxton (Toronto, 1987).

The following should be added to Roy’s works mentioned in the biography: Ma vache Bossie (Montréal, 1976) and Courte-queue (Montréal, 1979), which were both published in Contes pour enfants (Montréal, 1998) and translated by Alan Brown as My cow Bossie (Toronto, 1988) and Cliptail (Toronto, 1980); De quoi t’ennuies-tu, Éveline? (Montréal, 1982); and L’espagnole et la pékinoise (Montréal, 1986), published also in Contes pour enfants and translated by Patricia Claxton as The tortoiseshell and the Pekinese (Toronto, 1989).

Cite This Article

François Ricard, “ROY, GABRIELLE (baptized Marie-Rose-Emma-Gabrielle) (Carbotte),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 21, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 27, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/roy_gabrielle_21E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/roy_gabrielle_21E.html |

| Author of Article: | François Ricard |

| Title of Article: | ROY, GABRIELLE (baptized Marie-Rose-Emma-Gabrielle) (Carbotte) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 21 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 27, 2024 |