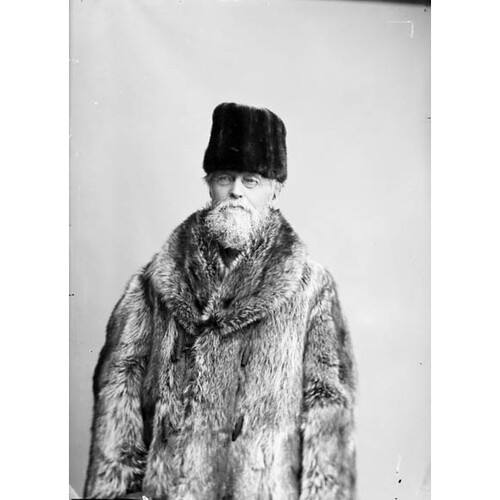

SELWYN, ALFRED RICHARD CECIL, geologist and civil servant; b. 26 July 1824 in Kilmington, Somerset, England, son of the Reverend Townshend Selwyn and Charlotte Sophia Murray; m. 1852 his cousin Matilda Charlotte Selwyn (d. 1882), and they had nine children; d. 19 Oct. 1902 in Vancouver.

Alfred Selwyn belonged to a well-to-do family; his father was a canon of Gloucester Cathedral and his mother was the daughter of the bishop of St David’s. He was tutored privately and then sent to Switzerland to further his education. The experience abroad was said to have focused his love of nature on geology and to have honed mountaineering skills that would prove useful in his professional career.

Appointed on 1 April 1845 as assistant geologist to the field staff of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, Selwyn joined a pioneering group of stratigraphers assigned to outline the country’s geological structures. He benefited from intense field training with Andrew Crombie Ramsay, the survey’s local director. Selwyn’s maps of the complex Lower Silurian formations of north Wales and western England were recognized as models of careful detail and were hailed by Ramsay as “the perfection of beauty.” For these important contributions, Selwyn was promoted geologist on 1 Jan. 1848.

In July 1852 the Colonial Office appointed Selwyn as geological surveyor to the newly founded Australian colony of Victoria, and later made him director of its geological survey. Beginning the work in 1853, Selwyn was well qualified to analyse the colony’s Silurian strata, replete with gold and fossils. He also assessed the coal-and gold-fields of Tasmania and South Australia.

Selwyn remained with the Victoria survey for 16 years. He also served other important public functions in Victoria as a member of the Mining Commission, the Board of Science, the Board of Agriculture, and commissions for the exhibitions at Victoria (1861), London (1862), Dublin (1865) and Paris (1866). Selwyn resigned from the survey in 1869, the legislature having discontinued its funding as a result of a disagreement over the survey’s priorities.

Before leaving Australia in March 1869, Selwyn accepted an offer from Sir William Edmond Logan* to become his successor as director of the Geological Survey of Canada. The task of filling the enormous gap left by the departure of Logan’s independent wealth, social status, political acumen, and scientific reputation, both in Canada and abroad, was daunting even for a stratigrapher of Selwyn’s dedication, training, and experience. The complexity of the task was increased immeasurably by the transformation of the GSC into a transcontinental and modern institution, which Selwyn was to oversee. This transition was even more difficult because Selwyn was an outsider among long-time members of the GSC who had coveted the directorship after Logan’s retirement, and some resented Selwyn’s appointment, which began on 1 December.

The path of Selwyn’s career with the GSC was governed by these structural and personal realities. His first official challenge was to learn enough about Canadian geology to supervise its more detailed investigation by the staff, no mean feat with the entry of Manitoba and British Columbia into confederation soon after his arrival. During his first season, in 1870, Selwyn inspected the Eastern Townships of Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. In 1871 he crossed British Columbia to help plan the GSC’s contribution to the building of the proposed Pacific railway. The next year he studied Precambrian formations between lakes Superior and Winnipeg and in 1873 the prairie lands between Winnipeg and the Rocky Mountains. In 1875, accompanied by botanist John Macoun*, Selwyn went back to British Columbia to concentrate on the proposed Peace River pass for the railway through the Rockies. The years 1876–79 saw his return to central Canada to review Logan’s analysis of the Quebec group of strata, which was being challenged by the GSC’s former chemist and mineralogist, Thomas Sterry Hunt*. Selwyn’s report offered a valuable attempt to systematize these Archaean formations as anticlinal rather than synclinal structures.

During Selwyn’s tenure two federal acts altered the conditions of the GSC’s existence. After funding had been increased for five years in 1872, an 1877 act designated the survey a branch of the Department of the Interior, subjecting it again to the less certain system of annual grants. The act assigned new responsibilities in natural history and ethnology to the survey and created four assistant directorships, changes which invited conflicts over priorities. It also announced plans to move the GSC from Montreal to Ottawa. This task was completed in 1881 but Selwyn was left to fight for adequate facilities. GSC staff were also to be integrated into the civil service, a measure accomplished in 1883. Legislation in 1890 reinstated the GSC as a separate department (albeit under the supervision of the minister of the interior), specified staff qualifications, and ordered the collection of statistics on Canadian mineral production.

While his staff carried on the survey of geological regions, Selwyn shifted the focus of the project from the broader strokes of reconnaissance to the finer details of smaller-scale mapping in selected type areas. In keeping with this process, he standardized the legends and colour schemes of Canadian geological maps in 1881. A member of the organizing committee of the International Geological Congress in 1878, Selwyn in 1889 began developing common nomenclature and mapping schemes with the United States Geological Survey. During the 1880s he added more highly educated staff to carry out the increasingly specialized tasks of the GSC. These included civil and mining engineers to construct base maps and develop a mining section, and a botanist (Macoun), zoologist, and taxidermist to conduct the survey of natural history.

Besides tending to extensive scientific and administrative responsibilities, Selwyn spent time abroad organizing Canada’s contributions to international exhibitions in Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1878), London (1886), and Chicago (1893). For these efforts he earned an lld from McGill College in 1881 and a cmg in 1886. When Montreal hosted the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1884, Selwyn led a field trip to British Columbia. His designation during his absences of George Mercer Dawson as acting director fuelled the resentment of Robert Bell* and others, some of whom suffered from inequities that invariably accompanied the GSC’s many recent transitions. Yet Selwyn’s personal qualities and personal experience contributed to these difficulties: his firm convictions were combined with a “hasty temper,” while discipline and orderliness found expression in a stern and official demeanour that expected deference and did not give praise easily. Intense animosities against Selwyn were aired publicly during the hearings of a select committee of the House of Commons which investigated the GSC in 1884. Little was resolved by the inquiry, and the bitterness continued. The circumstances of Selwyn’s retirement in 1895 proved awkward, since he was superannuated during a leave of absence in England and informed on his return that he had been replaced by Dawson. The following year Selwyn served as president of the Royal Society of Canada, capping his scientific career with an important address on the origin and evolution of Archaean rocks.

Selwyn belonged to a generation of British-trained stratigraphers who contributed greatly to 19th-century imperial geology. Although he emphasized both the economic aspects of the science and the solution of its complex structural problems, he was far less successful than Logan or Dawson in persuading the public of the important link between these geological activities.

A listing of Alfred Richard Cecil Selwyn’s publications appears in Science & technology biblio. (Richardson and MacDonald); there is also a bibliography of his works to 1894 in RSC Trans., 1st ser., 12 (1894), proc.: 70–71. Notable among his writings are: Notes and observations on the gold fields of Quebec and Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1872); “Notes on a journey through the North-West Territory, from Manitoba to Rocky Mountain House,” Canadian Naturalist (Montreal), new ser., 7 (1875): 193–216; “The stratigraphy of the Quebec group and the older crystalline rocks of Canada,” Canadian Naturalist, new ser., 9 (1881): 17–31; and “Presidential address: on the origin and evolution of Archaean rocks, with remarks and opinions on other geological subjects; being the result of personal work in both hemispheres from 1845 to 1895,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., 2 (1896), proc.: lxxviii–xcix.

Geological Survey of Canada (Ottawa), Directors’ letterbooks. ADB, vol.6. Dictionary of scientific biography, ed. C. G. Gillispie et al. (14v., New York, 1970–76). DNB. Geological Survey of Canada, Report of progress (Ottawa; Montreal), 1870/71–1882/84, continued as its Annual report (Montreal; Ottawa), new ser., 1 (1885)–8 (1895). R. A. Stafford, Scientist of empire: Sir Roderick Murchison, scientific exploration and Victorian imperialism (Cambridge, Eng., and New York, 1989). Zaslow, Reading the rocks.

Cite This Article

Suzanne Zeller, “SELWYN, ALFRED RICHARD CECIL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/selwyn_alfred_richard_cecil_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/selwyn_alfred_richard_cecil_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Suzanne Zeller |

| Title of Article: | SELWYN, ALFRED RICHARD CECIL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | November 25, 2024 |